The intoxicating languor of the Caribbean

From Repeating Islands

WRITTEN IN 1929, PAUL MORAND’S CARIBBEAN WINTER IS FINALLY AVAILABLE IN ENGLISH. IF YOU DISREGARD THE RACISM, IT’S A TRAVELOGUE THAT’S HARD TO BEAT

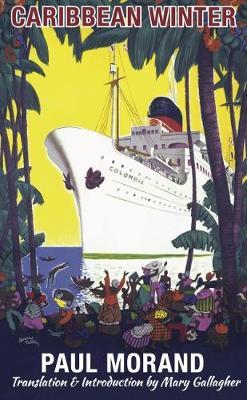

A review by Ian Thomson for The Spectator. Our thanks to Peter Jordens for bringing this item to our attention.Caribbean WinterPaul Morand, translated and with an introduction by Mary Gallagher

Signal Books, pp.£12.99, 171

Ian Fleming’s voodoo extravaganza Live and Let Diefinds James Bond in rapt consultation of The Traveller’s Tree by Patrick Leigh Fermor. ‘This, one of the great travel books, is published by John Murray at 25s’, proclaims a footnote in the first edition. Fleming was a friend of Leigh Fermor, so this is to be expected. Published in 1950, The Traveller’s Tree may still be the best non-fiction account of the West Indies. ‘It’s by a chap who knows what he’s talking about’, M tells 007, knowingly.

But Paul Morand’s 1929 Hiver caraïbe comes a close second. The question is: why has it taken 90 years for this masterwork to appear in English? Morand (1888–1976), a pro-Vichy collaborator and occasional Jew-baiter, was made persona non grata in post-Liberation France, and was shunned by mainstream publishers. Only in recent years has his reputation been revived somewhat.

His glancing, aphoristic prose did have its admirers, among them André Breton, Ezra Pound, Jean Cocteau and Leigh Fermor himself (who knew Morand personally and translated one of his books into English). For all that Morand was a sentimental, narcissistic snob, he remains a fine writer, whose Caribbean travelogue memorably conjures a tainted earthly paradise caught between the sun and the sea.

The result of two trips made to the West Indies in 1927, Caribbean Winter is inevitably distinguished by the casual racism of the time. ‘Gobineau’s theories seem quite sound to me’, Morand says of the half-baked 19th-century ethnologist Joseph Arthur de Gobineau, who viewed people of colour as little better than metamorphosed orangutans. Like Fleming after him, Morand was repelled by notions of hybridity; just as the Jamaican Chinese baddies in Dr No are depicted as yellow-black ‘Chigroes’ (an impure race, no less), so Morand quaked at the ‘filthy epoch of the half-caste’, as he found it in the Caribbean.

His fear and loathing of miscegenation was not confined to European apologists for Aryanism. Marcus Garvey, the Jamaican-born messiah of black liberation, likewise viewed any union between black and white as a social misfortune. Mixed marriages threatened the wholesale ‘bastardy’ of the black race, reckoned Garvey. Morand doubtless viewed the Garveyite Black Power movements of 1920s New York as an equivalent, anti-white racism, though the analogy is absurd because people with white skin generally enjoy the liberty of not having to define themselves in terms of race.

But beyond his narrow race politics, Morand is a wonderful guide to the Caribbean, as he is clearly enchanted by the local colour and intoxicating, noontide languor. Stretching in a long arc from Florida to Venezuela, the islands are each vastly different in their collisions of history, race, conquest and tongues. If parts of Jamaica remind Morand of a semi-tropical Isle of Wight (‘golf courses, hotels and winter woollies’), Haiti is a slice of West Africa set floating in the Antilles. Among the many Haitian notables commemorated by Morand is Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, father of Alexandre Dumas, author of The Three Musketeers, who in turn was the father of Alexandre Dumas fils, author of La Dame aux Camélias. (Thomas-Alexandre’s birthplace of Jérémie in southern Haiti has a main square called, simply, Place des Trois Dumas.)

Morand’s mandarin and determinedly insouciant prose is a delight to read (the sky over Cuba is the ‘colour of a turtle-dove’s breast’). He served as a French diplomat in London during the first world war, and was a cultivated if consciously dandified man of letters. His impressions of the French Windward Islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe are enlivened by learned allusions to Goya, early Flemish art and the ‘curly-haired waves’ of Hokusai. The humour throughout is pungent, if occasionally spiteful. (Morand’s great 1971 account of Venice, Venises, typically excoriated American hippies for their want of personal hygiene: ‘Their armpits smelt of leeks, their buttocks of venison’ — a very French observation.)

Caribbean Winter, brilliantly translated by Mary Gallagher, is a glowing, incantatory work of genius that can profitably be read in tandem with Morand’s marvellous 1921 trilogy of Proustian novels set in London, Tender Shoots.

For more on this story go to: https://repeatingislands.com/2019/01/04/the-intoxicating-languor-of-the-caribbean/