2020 Atlantic Hurricane Season expected to be more active than usual, NOAA says

By Brian Donegan From Weather Underground

The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season is predicted to be more active than usual, according to an outlook released Thursday by NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center, a division of the National Weather Service.

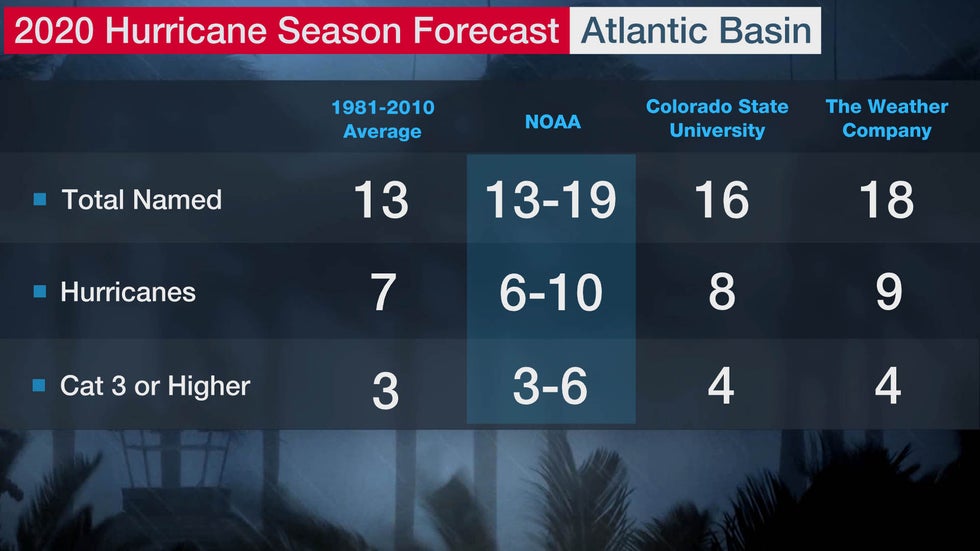

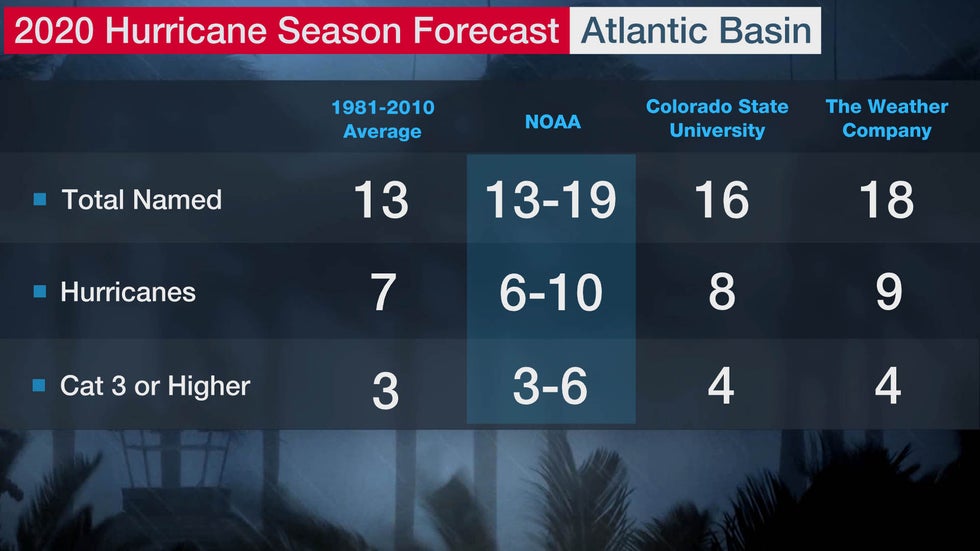

The NOAA outlook calls for 13 to 19 named storms, six to 10 hurricanes and three to six major hurricanes – one that is Category 3 or higher (115-plus-mph winds) on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale.

This forecast is above the 30-year (1981-2010) average of 13 named storms, seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes.

NOAA’s outlook is in agreement with that released in April by The Weather Company, an IBM Business, which calls for 18 named storms, nine hurricanes and four major hurricanes.

Numbers of Atlantic Basin named storms (those that attain at least tropical or subtropical storm strength), hurricanes and hurricanes of Category 3 or higher intensity forecast by NOAA, Colorado State University and The Weather Company, an IBM Business, compared to the 30-year average (1981 to 2010).

Though the official Atlantic hurricane season runs from June through November, storms can occasionally develop outside those months. This was the case earlier in May when Tropical Storm Arthur formed, as well as the past five seasons with Subtropical Storm Andrea in May 2019, Tropical Storm Alberto in May 2018, Tropical Storm Arlene in April 2017, Tropical Storm Bonnie in May 2016, Hurricane Alex in January 2016 and Tropical Storm Ana in May 2015.

Arthur is included in NOAA’s tally of the 13 to 19 named storms it expects this season.

NOAA’s outlook is based on a number of climate factors, including the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and sea-surface temperatures in the Atlantic Basin.

ENSO conditions are expected to remain either neutral (neither El Niño nor La Niña) or trend toward La Niña, which means El Niño will not be present to suppress hurricane activity.

Additionally, warmer-than-average sea-surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, combined with reduced wind shear – the change in wind speed and/or direction with height – weaker trade winds in the tropical Atlantic and an enhanced west African monsoon all increase the odds of an above-above hurricane season.

Similar conditions have been producing more active seasons since the current high-activity era began in 1995, NOAA said.

For example, 2010 tied for the third-most-active Atlantic hurricane season on record for named storms, with 19, 12 of which became hurricanes. 2017 was the fifth-most-active season, with 17 named storms and 10 hurricanes, including major hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria.

“NOAA’s analysis of current and seasonal atmospheric conditions reveals a recipe for an active Atlantic hurricane season this year,” said Dr. Neil Jacobs, acting NOAA administrator. “Our skilled forecasters, coupled with upgrades to our computer models and observing technologies, will provide accurate and timely forecasts to protect life and property.”

While you should prepare for hurricane season every year, it is critically important to do so this year.

“As Americans focus their attention on a safe and healthy reopening of our country, it remains critically important that we also remember to make the necessary preparations for the upcoming hurricane season,” said Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross. “Just as in years past, NOAA experts will stay ahead of developing hurricanes and tropical storms and provide the forecasts and warnings we depend on to stay safe.”

NOAA’s outlook is for overall activity expected during the hurricane season and is not a landfall forecast. It will update the 2020 seasonal outlook in August prior to the historical peak of the Atlantic season.

Here are some questions and answers about what this outlook means.

What Does This Mean for the United States?

There is no strong correlation between the number of storms or hurricanes and U.S. landfalls in any given season. One or more of the 13 to 19 named storms predicted to develop this season could hit the U.S. or none at all. That’s why residents of the coastal U.S. should prepare each year no matter the forecast.

A couple of examples of why you need to be prepared each year occurred in 1992 and 1983.

The 1992 season produced only six named storms and one subtropical storm. However, one of those was Hurricane Andrew, which devastated South Florida as a Category 5 hurricane.

In 1983, there were only four named storms, but one was Alicia. The Category 3 hurricane hit the Houston-Galveston area and caused almost as many direct fatalities there as Andrew did in South Florida.

In contrast, the 2010 Atlantic season was quite active, with 19 named storms and 12 hurricanes. Despite the high number of storms that year, no hurricanes and only one tropical storm made landfall in the U.S.

In other words, a season can deliver many storms but have little impact, or deliver few storms and have one or more hitting the U.S. coast with major impact.

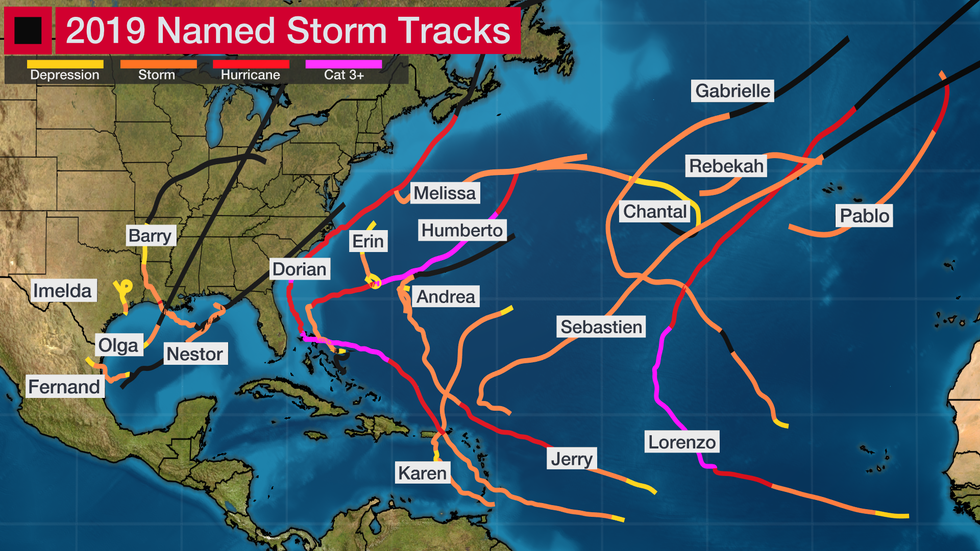

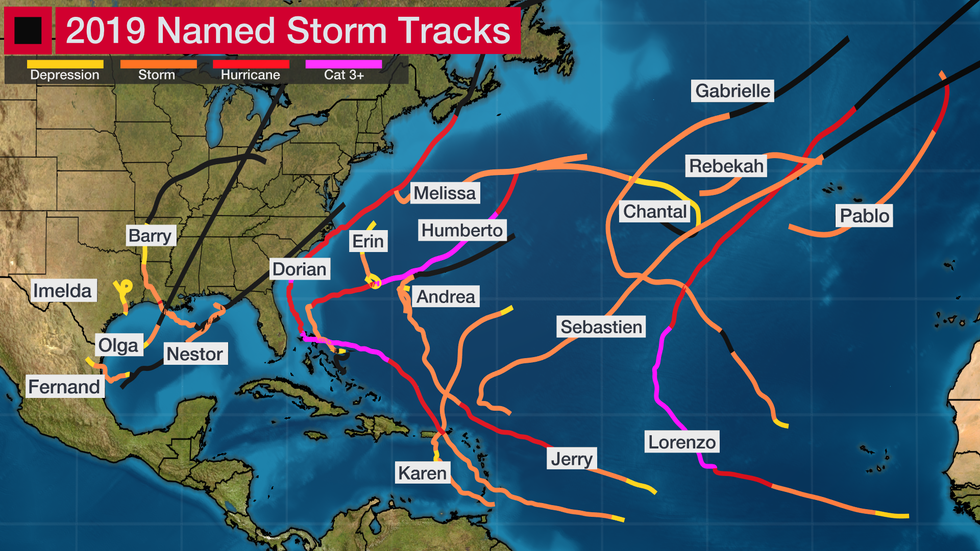

Named storm tracks in the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season. The colors correspond to intensities of each named storm during that section of the track, except for the black sections, which correspond to either a remnant or the time during which a system was a tropical wave before forming into a depression or storm.

The U.S. averages one to two hurricane landfalls each season, according to NOAA’s Hurricane Research Division statistics.

In 2019, there were two U.S. hurricane landfalls – Barry in Louisiana and Dorian in North Carolina.

In 2018, four named storms impacted the U.S. coastline, most notably hurricanes Florence and Michael within a month of each other.

In 2017, seven named storms impacted the U.S. coast, including Puerto Rico, most notably hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria, which battered Texas, Florida and Puerto Rico, respectively.

Before that, the U.S. was on a bit of a lucky streak.

The 10-year running total of U.S. hurricane landfalls from 2006 through 2015 was seven, according to Alex Lamers, a meteorologist at the National Weather Service. This was a record low for any 10-year period dating to 1850, and considerably lower than the average of 17 per 10-year period in that same span.

None of the U.S. landfalls from 2006 through 2015 were from major hurricanes.

So it’s impossible to know for certain if a U.S. hurricane strike will occur this season. Keep in mind that even a weak tropical storm hitting the U.S. can cause major impacts, particularly if it moves slowly and triggers flooding rainfall.

How Much of a Role Will El Niño or La Niña Play?

El Niño/La Niña, the periodic warming/cooling of the equatorial eastern and central Pacific Ocean, can shift weather patterns over a period of months. Its status is always one factor that’s considered in hurricane season forecasting.

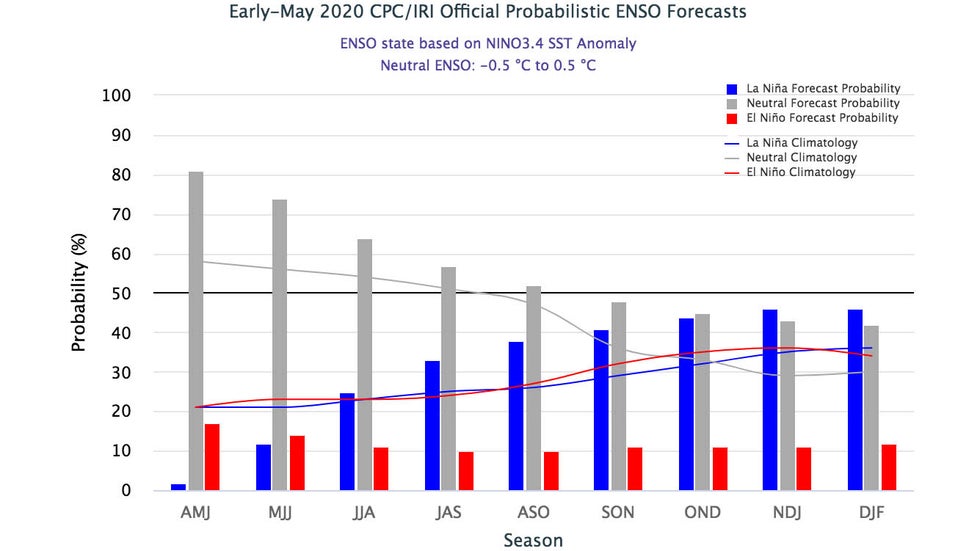

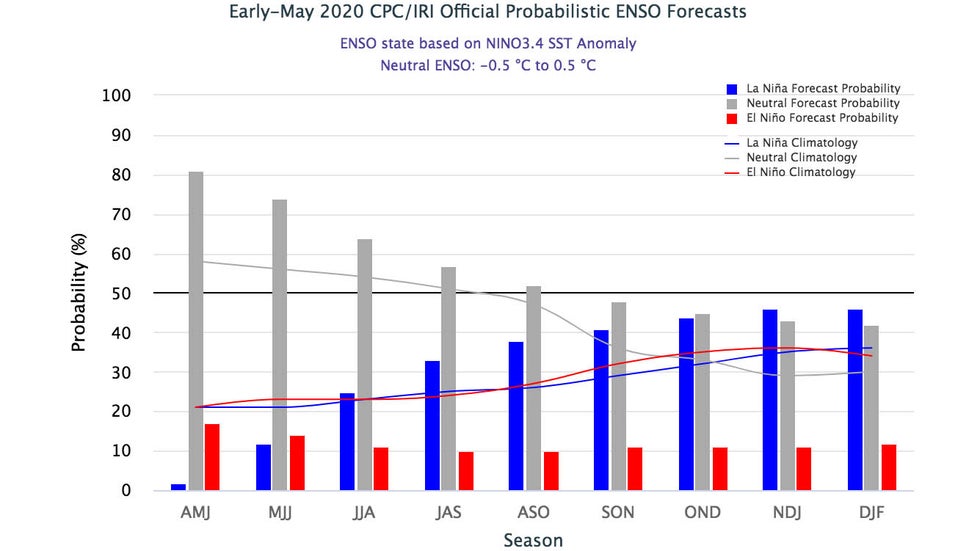

As of late spring, neither El Niño nor La Niña were in place. NOAA forecasts a 65% chance of these neutral conditions continuing during the summer ahead.

Long-range forecasters at both The Weather Company, an IBM Business, and Colorado State Universitywere generally in agreement with NOAA, suggesting that neutral conditions are anticipated through at least the first half of the hurricane season (June through August, or JJA), with either neutral or La Niña conditions possible in the second half (September through November, or SON).

El Niño/La Niña Outlook into Early 2021

We should note here, before talking about the impacts of a possible La Niña, that the status of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is notoriously difficult to predict. This is especially true from February to May, when the “spring predictability barrier” is in play, a period when forecast skill is lower than the rest of the year.

La Niña generally acts as a speed boost to the Atlantic hurricane season, but it is just one factor that can lead to an active year. Hurricane seasons can be active even if La Niña is not in play.

La Niña typically corresponds with a more active hurricane season because the cooler waters of the Eastern Pacific Ocean end up causing less wind shear along with weaker low-level winds in the Caribbean Sea. La Niña can also enhance rising motion over the Atlantic Basin, making it easier for storms to develop.

The La Niña years of 2010 and 2011 are among several tied for the third-most-active Atlantic seasons on record (both years had 19 named storms). The next La Niña year, 2016, was also active, with 15 named storms that included Category 5 Matthew and three other major hurricanes. La Niña conditions recurred midway through the hyperactive and catastrophic 2017 season that produced Harvey, Irma and Maria.

Other Factors in Play

One of the other ingredients that meteorologists, including those at NOAA, are considering for hurricane season is current sea-surface temperatures across the Atlantic Ocean.

Much of the Atlantic’s waters are already warmer than average as of late May. The Gulf of Mexico is also several degrees above average, given the hot temperatures and lack of rain over the Southeast earlier in the spring.

But it isn’t ocean temperatures in April that will help boost or curtail tropical systems; rather, it is water temperatures during the hurricane season.

Climate models suggest that most of, if not the entire, Atlantic Basin will be warmer than average during the peak of the hurricane season.

Forecast Sea-Surface Temperature Anomalies for August through October 2020

An above-average number of tropical storms and hurricanes is more likely if temperatures in the main development region (MDR) between Africa and the Caribbean Sea are warmer than average. Conversely, below-average ocean temperatures can lead to fewer tropical systems than if waters were warmer.

Assuming atmospheric factors are favorable, warmer waters in the MDR allow tropical waves – the formative engines that can eventually become tropical storms – to get closer to the Caribbean and the U.S.

The prevalence of wind shear and dry air across the Atlantic will also need to be watched over the next six to eight months.

If neutral or La Niña conditions do lock in, as most forecasters expect, and the atmosphere responds to it, there could be less wind shear and more favorable conditions for hurricane growth toward the end of the season.

How much dry air rolls off the coast of Africa will also need to be monitored. Even if water temperatures are very warm and there is little wind shear, dry air can still disrupt developing tropical cyclones and even prohibit their birth.

Hurricanes need a precise set of ingredients to come together in order for them to fester, and those ingredients will need to be monitored this year.

The Atlantic hurricane season officially begins June 1 and runs through Nov. 30. This article provides a list of potentially life-saving tips to help you prepare for a hurricane.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

For more on this story go to: https://www.wunderground.com/article/safety/hurricane/news/2020-05-21-atlantic-hurricane-season-april-outlook-noaa-the-weather-company