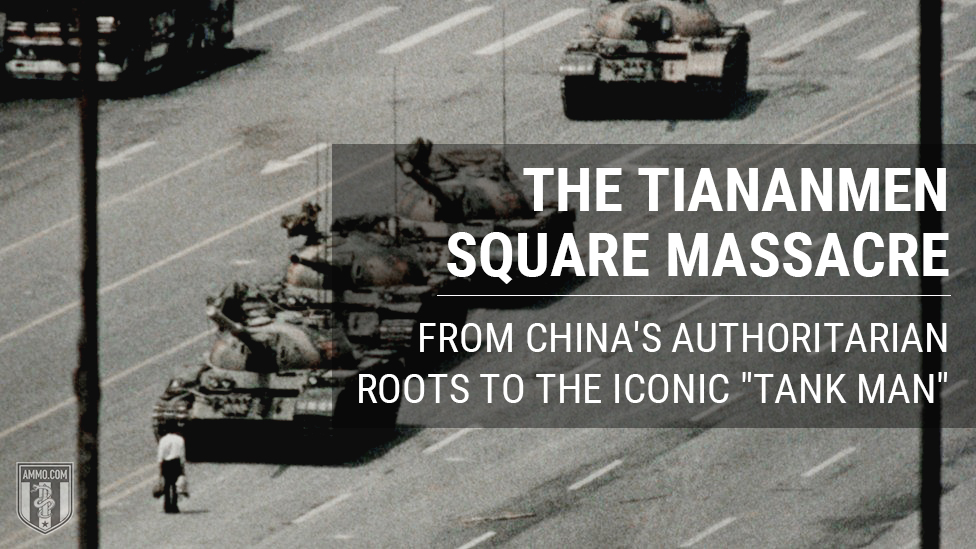

The Tiananmen Square Massacre: From China’s authoritarian roots to the iconic “Tank Man”

From Ammo.com

China is often described as the next superpower to top America within the next few decades. At first glance, such an assertion makes sense. The country’s vast geography, natural resources, rich history, and tech-savvy populace puts it in a position to thrive in the 21st century. However, China’s rise as a superpower is not one of an overnight success, nor is it filled with pretty rainbows.

Indeed, China is one of the world’s longest lasting civilizations, with cultural and political traditions that have been passed down to succeeding generations effortlessly. With such a vast history, China had gone through its own zeniths and nadirs. As is the nature of any civilization. However, China’s modern history has been a rollercoaster ride to say the least.

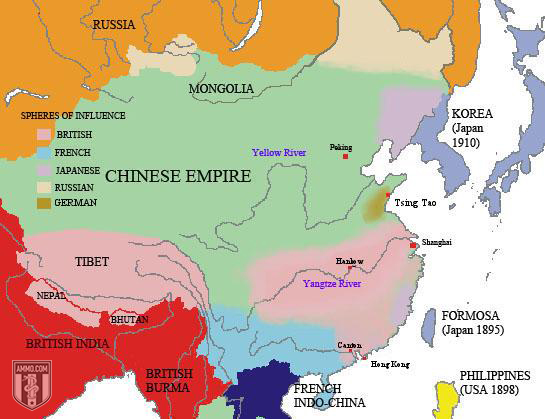

Despite having a massive formal governing apparatus that would put many empires to shame, China has not always had full control of its territorial jurisdiction. Once European powers reached Chinese shores in search of riches, they soon wanted their piece of pie. That meant slowly whittling away at Chinese territory. As the first movers in the Age of Exploration, the Portuguese and their missionaries colonized Macau.

Although the Portuguese’s venture was not exclusively about riches, it inspired other European actors such as the British to go and exploit China’s vast resources. Naturally, the Qing dynasty and Britain’s interests clashed once the British wanted to expand trade inside the country. What was originally a trade dispute between a Qing government wanting to maintain trade that overwhelmingly favored China, soon turned into a full-blown conflict as seen in the Opium War.

China was handed a humiliating defeat, which saw it turn over Hong Kong to the British. This marked a turning point in Chinese history. The once mighty country slowly deteriorated both internally and externally. China soon became a punching bag for smaller, yet more militarily advanced countries that started setting up trading outposts in Shanghai. Indeed, these moves were not welcome by the Chinese and many in the Qing court, but due to the country’s decaying institutions, it could do nothing to prevent further predations.

Even empires on the Western periphery, like Imperial Russia, started to prey on China when it annexed all of the Chinese land north of the Amur River in 1858, exploiting Chinese weakness along a border that was, at the time, 4,650 miles long. As if China’s foreign reversals weren’t enough, Imperial Japan also jumped in the mix and picked apart China like other European powers. Japan put the world on notice when it crushed China in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894. As a result of this humiliation, Japan added the island of modern-day Taiwan, the Liaodong Peninsula, and the Korean peninsula into its sphere of influence. Japan’s exploitation of its weaker mainland rival did not stop there.

Even after the Qing dynasty collapsed, nationalist leader Chiang Kai-Shek tried to put the political pieces back together during the 1920s, in an attempt to unify the country and restore Chinese greatness. However, Imperial Japan was ready to humiliate China yet again, when it invaded Manchuria in 1931, and occupied it until 1945, in an attempt to expand their industrialization efforts.

All in all, the mid-19th century up until the mid-20th century was a rocky period. It took game-changing events after World War IIfor China to finally get its political house in order and build itself up on its own terms.

Table of Contents

- China: From Powerful Imperial Rule to a Weakened State

- The Move to Unify the Chinese State

- Unifying the Chinese State Under Communism

- The Omnipresent Chinese Bureaucracy

- Geopolitical Tensions Create New Openings

- The Economic and Political Transformation of Deng Xiaoping’s China

- The Historical Significance of Tiananmen Square

- Chinese Leadership Becomes Weary of the Threat of Democratic Reforms

- The Birth of Tank Man

- China’s Authoritarianism Lives On

China: From Powerful Imperial Rule to a Weakened State

As foreign powers such as the United States, Germany, Japan, and Russia carved out spheres of influence in the once-mighty empire, the Chinese imperial court began to lose legitimacy both domestically and abroad. In 1911, the Xinhai Revolution was the final straw that broke the Qing dynasty’s back. Chinese reformers grew tired of their country’s weakness and organized revolts across the country that ultimately forced the last Qing emperor, Pu Yi, to abdicate in 1912. However, the transition from empire to a modern-day nation-state was filled with many road bumps for China.

Despite political reformer and provisional president of the Republic of ChinaSun Yat-sen’s attempts to modernize the Chinese state, the country was quickly mired in internal struggles that prevented it from forming a coherent political structure in the immediate years following the fall of the Qing dynasty. Warlord control of the country soon became the norm as many optimistic Chinese reformers then realized the road to Chinese political stability would not come easy.

The Move to Unify the Chinese State

By the 1920s, China’s political destiny slowly started to change.

It wasn’t until the 1920s that movements began to emerge, with hopes to unify China and establish it as a sovereign nation free of foreign exploitation. The emergence of the Nationalist and Communist movements in China appealed to nationalistic sentiment among the populace. Their messages, while ideologically different in economic matters, had a vision of restoring China’s rightful place on the world stage. They viewed the Qing dynasty as corrupt and feckless for allowing European powers and Japan to carve out the country. For China to be great, it had to be free of foreign influence.

The dream of a unified China nearly became a reality when the Nationalist (Kuomintang) movement led by Chiang Kai-Shek ended warlord rule and began consolidating the Chinese state. However, hopes of a unified China on both ideological and political lines were temporarily dashed when the Japanese invaded in the 1930s. The subsequent expansion of World War II to the Asian theater saw the previously dominant Nationalist forces having to fend off Japanese forces. Such fighting left the Nationalist forces greatly depleted, while their Communist foes pulled their forces in the Chinese interior.

Little did the Nationalists know that once World War II came to an end, they would be up against a replenished and emboldened Communist movement. And this time around, they would not go down without a fight.

Unifying the Chinese State Under Communism

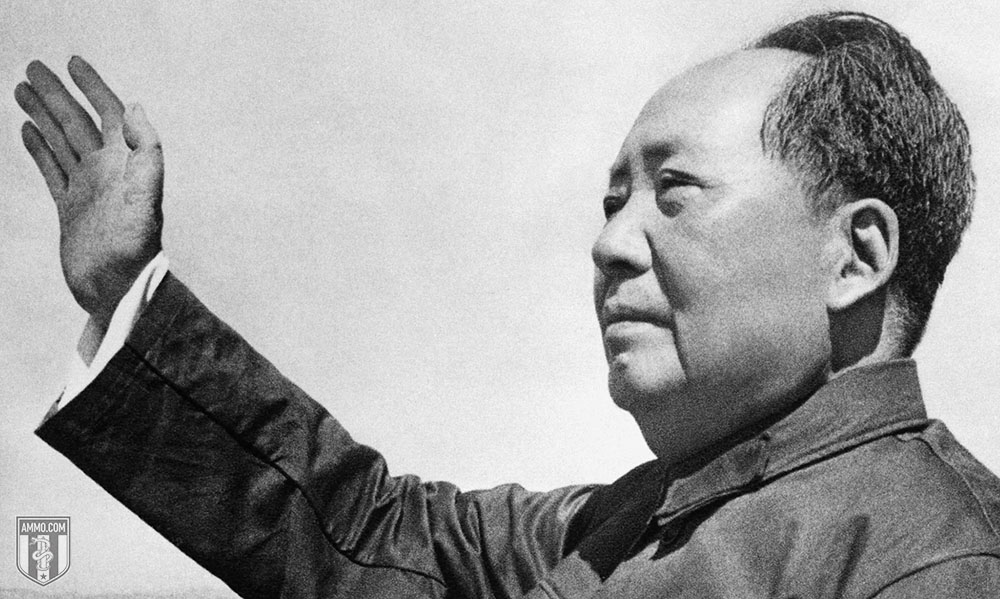

Once the dust settled from World War II, national unity went out the window. Communist forces under Mao Zedong were ready to duke it out with Chiang Kai-Shek and his Nationalist faction. So began the second phase of the Chinese Civil War (1945-1949). After four years of hard fighting, the Communists defeated the already depleted Kuomintang in 1949. By October 1949, Mao Zedong’s communist government was ready to usher in a new era of consolidated rule in China by declaring the People’s Republic of China. In response, the defeated Nationalists scurried to the island of Formosa, which would be renamed as Taiwan or the Republic of China. Despite China’s stubbornness in de-legitimizing the independent nation on the world stage, Taiwan would remain under the thumb of Chiang Kai-Shek until his death in 1975.

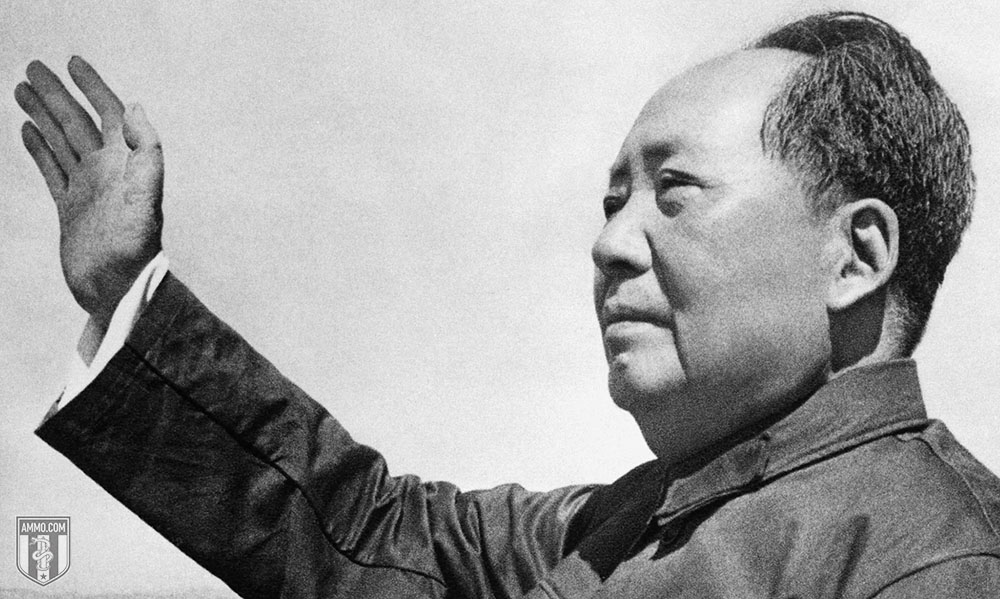

Once in command, Mao was focused on consolidating his internal power and centralizing the Chinese state at the domestic level. The Chinese leader was not so concerned about expanding China’s reach abroad during his first few years as Chairman of the Communist Party. Once his power was firmly established, he then proceeded to make China an industrial power conforming to principles of central-planning. China was no longer going to be the pushover that it once was in the latter half of the 19th century. It was ready to leave its mark on the international stage.

The Omnipresent Chinese Bureaucracy

The Chinese story is one of the eternal conflicts between centralized control and violent regionalism, as noted by Jacob L. Shapiro. Chairman Mao was faced with presiding over a large country with a long history of political violence. China encompasses such a vast territory, which necessitates large, bureaucratic systems to administer it. For political purposes, this bureaucracy has helped China maintain control over its jurisdiction in the short and mid-term. However, in the long-term this bureaucracy would become unwieldy and parasitic. As a result, high taxation and economic stagnation would follow after this bureaucracy became ingrained in the Chinese political system. This has been a fixture of China’s so-called “Dynastic Cycle,” which appeared to rear its ugly head in modern times. Communist Party elites did not want to become the next generation of leaders who fell victim to this vicious cycle.

Mao despised the Chinese bureaucracy and was able to rip it to shreds when he initially took the helm of the Chinese state. However, when Mao wanted to embark on the Great Leap Forward – an ambitious program created to rapidly change Chinese industry and agriculture through state planning – he had to come to grips with the reality that he needed a bureaucracy to carry out his grandiose vision.

Off to the bureaucratic races China went.

The Great Leap Forward

Fearful of Mao’s punitive actions, Chinese bureaucrats fudged data in order to placate him. What seemed like a political maneuver to gain favor within the government, would later turn out to be a disaster for the people living in the countryside. China’s Great Leap Forward experiment was initially marketed as the program to take China to the next level of economic development. The Great Leap Forward was a concerted effort to collectivize the Chinese economy and hand over the commanding heights to the Chinese state. Private property and a market-based price system were cast aside, while the Chinese central planners tried to play god.

But playing god with the economy comes with a massive price to pay. Even the best central planners are unable to break the laws of economics. Such heavy-handed interventions in the economy destroyed China’s agricultural sector. In turn, the decimation of Chinese agriculture created famine conditions, which led to the deaths of an estimated range of 20 million to 45 million people. The casualties suffered during the Great Leap Forward made China another tragic case of democide, as the country became another casualty of central planning. Consequently, Mao Zedong saw his political image tarnished after this failed socialist experiment, which called into question the validity of his political ideology. But the man-made disaster did not deter him from pursuing other ambitious political programs. Mao was intent on leaving his political mark in China.

The Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution of 1966 to 1976 was Mao’s final attempt to impose a top-down program on the Chinese populace. This ambitious political venture sought to re-assert proletarian values and rid Chinese society of subversive bourgeois elements. However, this social program turned into a wide-scale political purge that hamstrung economic growth and undermined the civil liberties of millions in China. Like the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution proved that Mao was too ambitious in socially engineering society according to his grandiose political vision. With two controversial efforts led by the Chinese state to radically transform the nation’s society, China’s political class started to become restless. Even the Communist Party knew that Mao took things too far. It was becoming clear that China was on the verge of falling into political chaos. A new course would need to be taken for the country to advance, lest it become another victim of its well established Dynastic Cycle. Several leaders in the Chinese Communist Party were ready to step up to the plate.

Geopolitical Tensions Create New Openings

Politics never occur in a vacuum. Countries’ destinies are often shaped by external events, or at the very least, must adapt to international trends. In its quest to become a global superpower, China was no stranger to this. During the ambitious Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution programs, China was experiencing significant changes in its foreign policy. Communism may have had a unified vision against the bourgeois classes, but it witnessed numerous splits among countries throughout the 20th century. National interests often see ideologically similar countries take antagonistic paths.

The Communist sphere was indeed a house divided once the Chinese state was well established and ready to plot its own course. China’s Soviet “Big Brother” would soon learn that China was ready to grow up and pursue its own agenda. Initially, disputes surrounding debts that China incurred during the Korean War and the border it shared with the Soviet Union caused unrest between the two superpowers. Many Soviet officials saw Mao’s leadership purges as a flashback to the brutal regime of Josef Stalin. As a result, Soviet leadership became weary of their Communist “little brother” down South. In the same token, the Chinese remembered their exploitation at the hands of the Russian Empire in the 19th century. Naturally, they had no interest in repeating the same predatory relationship with its northern neighbor.

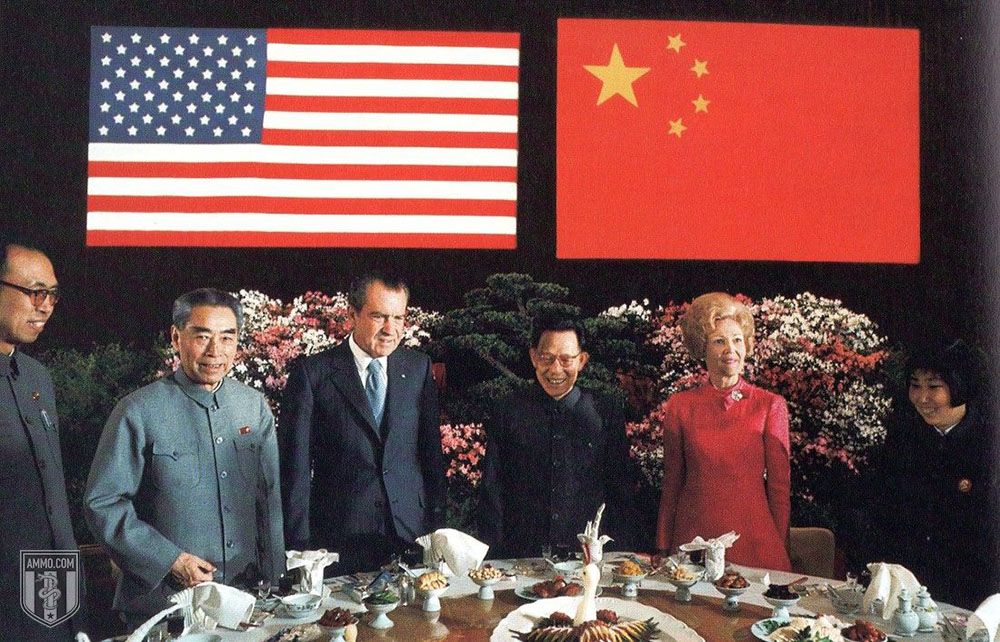

Looking from afar, America took advantage of this geopolitical tension by playing China off of the Soviet Union. The first concrete step in undermining the Soviet Union was Nixon’s visit to China in 1972, which helped re-establish diplomatic and trade relations between the two countries. With China now tasting the fruits of international capitalism, albeit to a limited degree, its old economic model of top-down control was on the ropes. Additionally, the failed Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution programs made the more pragmatic elements of the Chinese Communist Party reconsider Maoism. The economic benefits from restored relationships with America were simply too large to ignore. On top of that, the Chinese state could capture unprecedented economic benefits from opening up trade with America. This would enable China to not only grow economically, but also strengthen its governing apparatus. The Chinese state was then set for new leadership to emerge and continue integrating China into the global market. The days of Chinese isolation would soon come to an end.

The Economic and Political Transformation of Deng Xiaoping’s China

Once Deng Xiaoping succeeded Mao Zedong, China was poised for national greatness. Deng acknowledged that Maoism did not bring about its desired results for China, and a new economic program was needed to bring the country back to its feet. Now that the Communist Party was well entrenched in power and China was able to pacify any internal threats, the country was ready to interact with the outside world on its own terms. Gone were the days that China would be bullied by the West.

Recognizing the failure of central planning, while also taking into account the economic potential China had on the international stage, Deng Xiaoping embarked on a series of bold reforms. Unlike its humiliating experience of the late 19th century, China was opening up its markets without being the victim ofgunboat diplomacy.

Deng’s regime enacted certain reforms that brought back market dynamics, albeit in limited form, to the Chinese economy. Land privatization and the creation of special economic zones helped make China more competitive on the international arena. According to certain reports, China’s annual GDP growth rate ranged from 9.5 to 11.5 percent from 1978 to 2013. Thanks to these market-based reforms, China’s GDP increased tenfold and, as a result, millions of Chinese were lifted out of poverty. The horrific scenes of the Great Leap Forward soon became a distant memory as skyscrapers dotted illustrious cities like Shanghai, and factories were built left and right to bolster China’s breakneck industrial growth. “Made in China” soon became a staple of China’s economic prowess, as it flooded the world with basic goods coming out of its factories. But this could never have been possible without China making an attempt to open up its markets.

As Milton Friedman observed, economic freedom is generally a precondition for political freedom. When societies see economic freedoms gradually expanded, the new rich and emerging middle classes begin demanding more political freedoms.

As Chinese economic growth soared throughout the 1980s, its citizens demanded more than just economic prosperity. The death of pro-reform Communist leader Hu Yaobang in April 1989, caused several disturbances throughout the country. While on the economic uptick, Post-Mao China was marked by political uncertainty and Hu’s death added more fuel to the fire. Both the general populace and the political elite were rocked by the market reforms of Deng’s regime, which benefited some members of the newly rising entrepreneurial class, but still did not satisfy China’s humbler citizens.

The ruling elite also faced some questions about political legitimacy. Some of the concerns centered around corruption, employment prospects, inflation, and political freedoms. China’s student class started to demand new freedoms such as democracy, transparency in government, and free speech rights among other things. Protests started to pop up throughout the country, with the main ones centering around Tiananmen Square in Beijing.

The Historical Significance of Tiananmen Square

Historically, Tiananmen Square held great significance in Chinese politics. It was the place where the May Fourth Movement of 1919 occurred, when students’ protests aired grievances with the Chinese government’s tepid response to the Treaty of Versailles, which awarded Japan territories in the Shandong province. This movement helped jumpstart the Chinese Communist and Nationalist movements respectively.

Fast forward 30 years, the Proclamation of the People’s Republic of China by Mao Zedong on October 1, 1949, took place on Tiananmen Square as well. This marked the end of the Chinese Communist Revolution (1945-1949) and ushered in the Communist Party’s dominance over Chinese politics.

In 1989, student protestors sought to use this same square as their platform to make history by demanding the introduction of basic civil liberties – such as free speech and the right to peacefully assemble against the government – concepts which were unheard of throughout China’s long political history. In the fateful month of April 1989, they took to the streets in protest. Indeed, these students made history, but things didn’t go as planned for them.

Chinese Leadership Becomes Weary of the Threat of Democratic Reforms

Wanting to preserve the Communist Party’s political supremacy at all costs, China’s paramount leader, Deng Xiaoping, along with his Communist Party brain trust, perceived the protests as a political threat. Wasting no time in responding to these protests, the Chinese government proceeded to use force after the Chinese State Council declared martial law on May 20th, and deployed approximately 300,000 troops to Beijing. When troops arrived in Beijing on June 4th, they began killing protestors and bystanders.

The Chinese government arrested thousands of protesters, cracked down on other demonstrations in the country, kicked out foreign journalists, censored coverage of the Tiananmen incident in the press, bolstered police powers, and purged officials it believed to be receptive to the protestors’ cause. Estimates pin the death toll from several hundred to thousands.

Unsurprisingly, this incident received international condemnation. However, China’s status as a nuclear power and its newfound prosperity positioned it where it could avoid any direct military confrontation from other countries who disapproved of its agenda. Unlike 19th century China, 20th century China could take bold political actions without the fear of international actors trying to directly attack it.

The Birth of Tank Man

A day after the crackdown, on June 5, 1989, one of the most iconic images from the Tiananmen protests emerged. A man, who would be known as Tank Man or the Unknown Rebel, stood in front of a convoy of tanks leaving Tiananmen Square.

The lead tank tried to maneuver past the man, but was met with nonviolent resistance. The man repeatedly shuffled in front of the tank to obstruct the tank’s path. After a while, the lead tank stopped in its tracks and the armored tanks behind it stopped as well. From there, a short pause began with the man and tanks remaining in a standstill.

The video footage then shows the man climbing on top of the tank’s turret and chatting with a crew member and the tank’s commander. After having a conversation, the man jumps back down and gets in front of the tank again. The standoff between the man and tank continued until two figures in blue came out and pulled the man to the side. To this day, witnesses at this event are unsure about who pulled the “Tank Man” to the side. Furthermore, the identity and fate of the man is still unknown, although there has been speculation that he was either executed or fled the country shortly thereafter.

China’s Authoritarianism Lives On

The Tiananmen Square massacre was indeed a turning point in Chinese history. After an unprecedented liberalization of the economy up until the late 1980s, the Chinese state firmly put the breaks on any type of political reform that would enhance political freedoms. China showed the entire world that it would put hard limits on freedom, even if it meant receiving stiff criticism from Western democratic governments. As a sovereign nuclear power, China could proceed with its domestic policy as it pleased, knowing full well that no other world power would try to aggress against it.

To this day, civil liberties that Westerners often take for granted are heavily restricted in China. Under the leadership of Xi Jinping, China has embarked on one of the most ambitious censorship programs in human history. Now the Chinese state is even puttingMuslim Uighurs in re-education camps, much to the chagrin of international human rights observers. The Tiananmen incident remains one of the most heavily censored topics in Chinese political discourse.

The iconic image of the man confronting the tanks is a strong symbol of mankind’s eternal struggle to achieve freedom. Despite its fantastic economic growth, China remains one of the more authoritarian countries in the world. Just like freedom did not come to the West overnight, basic freedoms will likely take decades before they firmly take root in China.

Until then, the Chinese state remains firm in its hold over the Chinese populace.

Written by Jose Nino

Ammo.com’s Resistance Library: Foreign Analysis

- Democide: Understanding the State’s Monopoly on Violence and the Second Amendment

- No Go Zones: A Guide to Western Failed States and European Secessionist Movements

- Land Reform and Farm Murders in South Africa: The Untold Story of the Boers and the ANC

- Venezuela and the Paradox of Plenty: A Cautionary Tale About Oil, Envy, and Demagogues

- Island Gun Laws: The History of Gun Control and Crime in Australia, New Zealand, and the UK

- The Italian Years of Lead: Could the Secret “Strategy of Tension” Foreshadow America’s Future?

- The U.S. of A-Bomb: How American Nuclear Weapons Changed the Course of Human History

- The Tiananmen Square Massacre: From China’s Authoritarian Roots to the Iconic “Tank Man”

SOURCE: https://ammo.com/articles/tiananmen-square-massacre-china-chinese-authoritarian-roots-tank-man