Caribbean 7.7 Quake: Two terrible myths and one great piece of advice

By Robin Andrews From Forbes

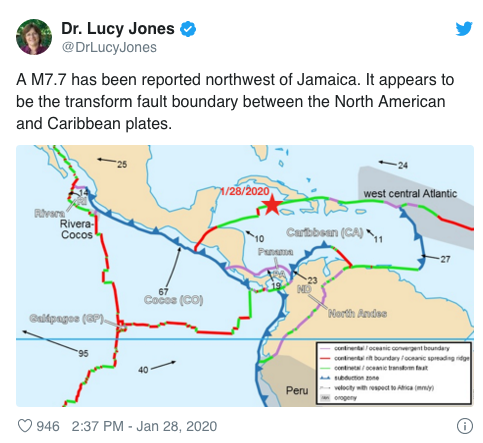

As plenty of you have likely noticed, a rather powerful magnitude 7.7 earthquake took place underwater, 10 kilometres (6.2 miles) beneath the seafloor, northwest of Jamaica and south of Cuba on Tuesday 28th. What is for now the mainshock in the sequence – the most powerful in a series of earthquakes – the 7.7 temblor was intense enough for its shaking to be felt all over the region, even as far as Miami, 710 kilometres (441 miles) away from the epicentre.

A few hours later, a magnitude 6.5 quake took place a little closer to the Cayman Islands, likely a potent aftershock of the 7.7 mainshock. Plenty of aftershocks will continue to rock the region for several weeks or months, with a small but non-zero chance that an earthquake more powerful than the current mainshock may also take place in the area.

Fortunately, despite some infrastructural damage in spots around the region, and the initial tsunami warning, this turned out to be nothing close to a tragedy. Apart from the fact that this earthquake took place a decent enough distance from settlements, the fault that ruptured was a strike-slip variety, wherein one ‘block’ moves sideways with respect to another. This normally doesn’t permit the mass movement of significant volumes of water – i.e. a tsunami – although there are some exceptions to this. In this case, no such hazardous tsunami was reported anywhere.

As with all powerful earthquakes, a few myths and pieces of misinformation skittered about online shortly after it happened. Right at the end of 2019, I put together a piece outlining some of the commonest, aggravating and sometimes downright dangerous misconceptions about major geological events – and surprise surprise, several of them reared their heads yet again during yesterday’s earthquake and tsunami scare.

First misconception: “Wow, this earthquake took place really close to the ones afflicting Puerto Rico at the moment. They must be connected, and I bet they’re going to trigger all kinds of earthquakes now around the Ring of Fire!”

Nope. The Ring of Fire doesn’t overlap with any of the quakes or fault lines within the Caribbean Sea, which contains Puerto Rico, Cuba and Jamaica, along with a myriad of other islands and several of the shorelines of Central and South American countries. The Ring of Fire is over in the Pacific, not the Atlantic. So there’s that. At least get your geography right.

In any event, the Ring of Fire is silly. This loop, which surrounds much of the vast Pacific Ocean, features constantly shifting, sliding and grinding plate boundaries, all with their own network of segregated or closely spaced faults. This continuous activity means that 75 percent of the world’s (known) volcanic activity and 90 percent of the world’s earthquakes take place along it.

Once more, for the people at the back: none of the eruptions that take place on the Ring of Fire are related to each other. And for the most part, none of the earthquakes are either. (There is a chance that some earthquakes can trigger volcanic eruptions if they are literally right on top of one another, but this is a very contentious subject with no concrete answers available at present.) It is a designation that really doesn’t make sense, geologically speaking.

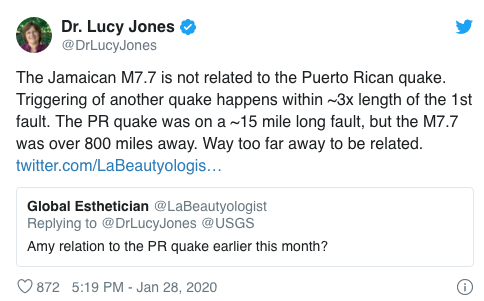

If two faults are close enough, a powerful earthquake on one can trigger an earthquake on another. In this case, the rule doesn’t apply, even though both earthquake sequences – Puerto Rico and Jamaica/Cuba/Cayman Islands – are taking place in the same sea. The general rule of thumb is that this triggering mechanism only applies when the second fault is no further away than three to four times the length of the original fault that ruptured.

As Caltech seismologist Lucy Jones took to Twitter to explain, the Puerto Rico mainshock took place on a 24-kilometre (15-mile)-long fault. That 7.7 quake yesterday was more than 1,300 kilometres (800 miles) away, or 53 times the distance of the fault that ruptured near Puerto Rico. There is no way these two earthquake sequences are connected.

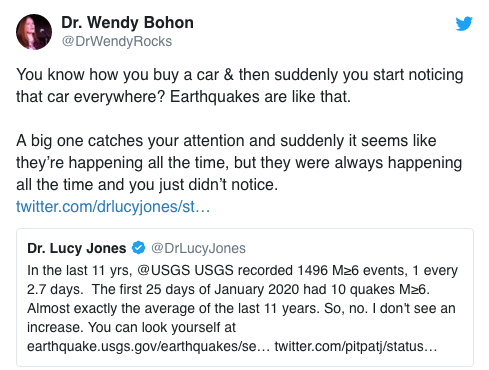

Second misconception: “There are a lot of earthquakes happening around the world at the moment, right?”

Nope. Earthquakes happen around the world on all flavours of fault lines in an essentially randomised manner. Most never get reported on, because they are too weak to be felt or, even if they could be felt, are too far away from human populations to cause any damage, or at least any significant damage.

Puerto Rico’s earthquakes have been making the news because they have produced intense enough shaking to cause damage and some deaths. Yesterday’s earthquake made headlines because it was very powerful, close to major population centres, and came with a potential tsunami risk. If both happened in the middle of nowhere with no tsunami risk, they wouldn’t have made the news.

More powerful earthquakes also happen far less frequently than less powerful ones. In the past 24 hours alone, there have been 137 earthquakes detected coming in at or above a magnitude 1.5. In the past week? 1,350 of them. This is all completely normal, and the vast majority of these haven’t made the news. The ones that did were, once again, the powerful ones that may have, or did, pose a risk to human populations.

The Earth is rocking no more, or less, than it was a year, decade, century or millennium ago. Don’t let the way it’s reported in the media distort that set-in-stone fact.

Amidst all this bemusement, a piece of advice from Susan Hough, a seismologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, stood out. Even though there was no tsunami accompanying this latest Caribbean temblor, and even though there was unlikely to be one, if those on the shorelines felt strong shaking, they should – no matter what, even if there aren’t sirens or alerts – have headed to higher ground.

Tsunami warnings are not always that precise, nor are they able to be given with sufficient time to trigger appropriate evacuations. The lethal Sulawesi tsunami in Indonesia in 2018 occurred on another strike-slip fault within a bay; compared to deep-sea tsunamis, it was able to slam into densely populated coastlines within a fraction of the time. Earthquakes were detected the moment they occurred, but the unique geography of the narrow bay produced a far more devastating tsunami that the strike-slip rupture otherwise would have done. This underestimation by the local authorities was combined with another problem: several cellphone towers were downed due to the quake, meaning that tsunami alerts were not sent out to all vulnerable populations. Thousands of people perished that day.

Crucially, strong shaking was felt on several coastlines within the bay prior to the tsunami’s arrival. And thus the mantra still stands: no matter what warning you have or haven’t got, and no matter what anyone else around you is or isn’t doing, if you feel strong shaking on a beach, get to higher ground.

For more on this story go to; https://www.forbes.com/sites/robinandrews/2020/01/29/caribbean-77-quake-two-terrible-myths-and-one-great-piece-of-advice/#c2a971b7dd64