Caribbean are messing with U.S. economic data

By Jeanna Smialek From Bloomberg

By Jeanna Smialek From Bloomberg

Companies shifting their profits to the Netherlands or Turks and Caicos probably have taxes in mind. But the consequences are felt well beyond the Internal Revenue Service ledger: growth and productivity also lose some upside.

Researchers have added back in shifted earnings to figure out how the increased offshore recognition has affected U.S. economic data, and theirs is the first study in this week’s economic research roundup. We also take a look at Chinese growth estimation, automation-born job loss and the distributional effects of longer life expectancy. Check this column each week for new and interesting studies from around the world.

Profit-shifting and productivity

U.S. multinational companies have increasingly attributed their profits to overseas affiliates for tax reasons, and that trend has taken some shine off of American growth and productivity statistics.

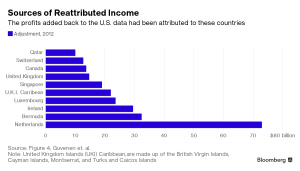

University of Minnesota economist Fatih Guvenen and co-authors find that correcting for profit-shifting activity raises aggregate productivity growth by 0.1 percent annually between 1994 and 2004 and 0.25 percent annually between 2004 and 2008. They saw no impact after 2008. The conclusion is that this isn’t the only thing driving the productivity slowdown, but it has been one cause. And while the mis-measurement worsening seems to have slowed down, “the problem itself still persists: From 2008 to 2014, domestic business-sector value added in the United States, on average, is understated by slightly more than 2 percent—or about $280 billion—per year.”

All of the lights (in China)

Here’s one for the China-data skeptics: the hypothesis that China’s growth is way overstated may be bunk. New York Fed economists Hunter Clark and Maxim Pinkovskiy and Columbia University’s Xavier Sala-i-Martin look at satellite-recorded nighttime light data in conjunction with other statistics related to economic activity, from official output figures to alternative indicators like bank loans, to determine how much attention to give each measure. They then look at how China’s growth has been doing based on an index that gives more weight to the best indicators. The results suggest that the officials numbers aren’t overly optimistic.

“Chinese growth rates are not appreciably less than officially reported growth rates, and may be considerably above them,” the authors write. “We find that GDP growth in 2015 Q4, a time when the financial press was awash with stories about a hard landing of the Chinese economy, is somewhat higher, but quite close to the officially reported rate.”

E-commerce is great for retail productivity, and terrible for retail workers. Industry headcount has been contracting at a 5,000 jobs-per-month pace for the past six months, and Goldman Sachs says that’s in large part explainable by the structural shift away from brick-and-mortar stores. Productivity is higher at e-commerce companies, which require 0.9 employee to generate $1 million in sales, versus 3.5 workers for brick-and-mortar stores.

Goldman economists see retail employment growth of 5,000 to 10,000 per month going forward, a slowdown from the historical trend, though that could drop even lower if automation in the industry picks up.

Not just a retail story

Globally, middle-income jobs have been disappearing amid technological advancement and economic integration. Between 1995 and 2009, the global income share of low- and middle-skilled labor dropped by more than 7 percentage points, and International Monetary Fund researchers trace that change back to automation and offshoring. In fact, sectors that are susceptible to technological disruption — like manufacturing and transportation — have seen especially big drops in labor share, whereas other industries like accommodation have actually seen labor share rise.

As richer Americans make life expectancy gains and age at death stagnates for lower-income groups, it’s bound to have distributional fallout. In new research, University of California at Berkeley economist Alan Auerbach and others look at the effects on benefits of longer projected lives — life expectancy at 50 for males in the two highest fifths of the income scale will climb between seven and eight years for people born in 1960 versus 1930, while the lowest two quintiles will see no progress. That will cause the gap between average lifetime benefits for the top versus the bottom rungs to widen by $130,000, considering programs including Social Security, disability insurance and Medicaid.

For more on this story and links to NBER website go to: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-04-18/profits-stashed-in-the-caribbean-are-messing-with-u-s-economic-data