Cayman Islands Right to Know Day 2017 Thu Sept 28

Freedom of Information Annual Statistics (2016-17)

Freedom of Information Annual Statistics (2016-17)

INTRODUCTION

The Freedom of Information Law (FOI Law) came into effect over eight years ago, and this report

provides part of the statistical background against which Freedom of Information (FOI) in the

Cayman Islands can be assessed.

As intended, the FOI Law has resulted in greater governmental openness and transparency since its

inception in January 2009. Across the Public Sector more information is being made available

proactively or upon demand than before, and where necessary, the FOI Law continues to provide

an important additional means of balancing the right to access with the legitimate need to withhold

some records. In its balanced approach, the Law starts from an assumption of openness by creating

a general right of access, but also restricts access for a number of specific, limited reasons

consistent with the system of constitutional democracy in the Cayman Islands. Where access

remains in dispute, requests can be internally reviewed and appealed to the Information

Commissioner for a decision.

METHODOLOGY

FOI requests are registered and tracked in a central tracking system (JADE) which is used by the

majority of information managers (IMs) in public authorities across the Public Sector. These

statistics have been compiled using aggregated statistics from JADE as well as individual reports on

FOI request activity from each public authority.

In past years the Information Commissioner’s Office ICO) noted discrepancies between the

aggregate statistics and the individual reports from each public authority. The ICO also monitors the

public authorities that appear not to be using JADE, even though the use of the government FOI

tracking system is a requirement of the Freedom of Information (General) Regulations, 2008

(regulation 24). In October 2016 the ICO completed a compliance investigation on this topic, during

which many public authorities brought themselves into compliance with regulation 24. However,

there were still ten public authorities not using JADE. It appears that number may have now risen to

fifteen and the ICO is now considering how to improve on these results.

When public authorities do not use JADE the statistics are not as accurate as they should be

although we make every effort to obtain the missing data from the individually produced FOI

request activity reports which show FOI requests not input into JADE. Data on internal reviews and

appeals continue not to be entered systematically, which means those statistics are largely nonexistent

(internal review) or need to be compiled from other sources (appeals).

JADE is owned and maintained by the Cabinet Office, and the ICO is grateful to the FOI Unit of the

Cabinet Office for providing many of the raw data for this report.

We hope that you will find this statistical report interesting and useful, and we encourage you to

contact the ICO if you have any further questions.

For ease of use and comparison with previous years, this report continues to represent FOI requests

and appeals in a July to June annual cycle (from 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2017).

TABLES

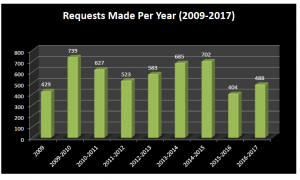

Following an initial spike shortly after the FOI Law came into effect in 2009, the number of requests

received by Government has varied from approximately 500 to 700. The overall trend was showing

a steady rise of the use of FOI by applicants. However, in 2015/16 there was a 42% drop in the

number of requests being made which has been followed by a 21% increase this past year.

Since the FOI Law came into effect in 2009 until 30 June 2017 approximately 5,180 requests have

been made.

Spread of FOI requests across the Public Sector (2016 – 2017)

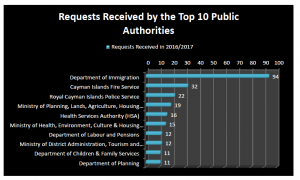

As in previous years, most FOI requests were directed towards those public authorities which hold

information that interests applicants most, and whose decisions impact individuals the greatest.

Most notably, the Cayman Islands Fire Service received 32 requests in the past year, after reporting

no requests in the 2015/16 fiscal year.

The ten public authorities receiving most FOI requests accounted for exactly half of all requests in 201617

-this proportion has remained consistent since 2009.

Response times

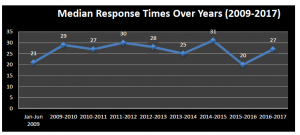

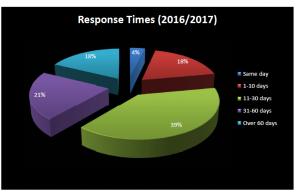

The FOI Law requires that public authorities give their initial response “as soon as practicable” but not

later than 30 calendar days after receiving a request. Response times went from the best median time

ever in 2015-16 (20 days) to 27 days in the past year.

As well, 39% of requests were responded to outside the initial 30 day time limit compared to 34% in

2015-2016. The following table shows the results for 2016-17.

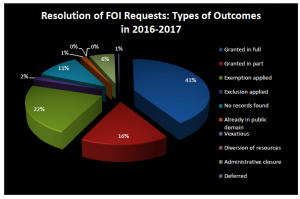

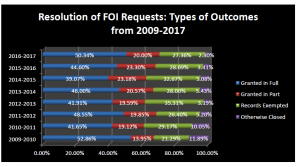

Resolution of FOI requests (2016-17 and trend from 2009 to 2017)

When responding to an FOI request, public authorities can grant access to the requested records in

full or in part. Alternatively, they can apply a number of exemptions or other reasons for

withholding the records.

Over the years, the proportion of requests granted in full or in part varied between a low of 44% in

the first half of 2009, and a high of 55% in 2011-12.

The actual proportion of requests granted in full or in part is larger when certain cases are

discounted i.e. where no records were found, where records were already in the public domain, or

where the request was a duplicate or withdrawn by the applicant, as shown in the graph attached.

Calculated this way, it is positive to note that the number of requests granted in full in 2016-17 was

approximately 6% higher than the 2015-16 year. Since 2009 about half of requests were either

granted in full or in part.

Resolution of FOI Requests: Types of Outcomes from 2009-2017 see attached

Breakdown of exemptions claimed (2016-17)

Paragraph (a) shall not be read so as to allow access to records

containing information that may not be disclosed under section 50 of

the Monetary Authority Law (2013 Revision);

Paragraph (a) shall not be read so as to allow access to records

containing information relating to the directors, officers and

shareholders of a company registered as an exempted company

under Part VII or VIII of the Companies Law (2013 Revision)

1

s. 3(5)(a)(i) This Law does not apply to the judicial functions of a court 1

s. 3(5)(a)(ii) This Law does not apply to the judicial functions of the holder of a

judicial office or other office connected with a court 1

s. 3(7) Nothing in this Law shall be read as abrogating the provisions of any

other Law that restricts access to records 2

s. 9(c) A public authority is not required to comply with a request where

compliance with the request would unreasonably divert its resources 1

s. 16(a)

Records relating to law enforcement are exempt from disclosure if

their disclosure would, or could reasonably be expected to endanger

any person’s life or safety.

2

s. 16(b)(i)

Records relating to law enforcement are exempt from disclosure if

their disclosure would, or could reasonably be expected to affect the

conduct of an investigation or presecution of a breach or possible

breach of the law.

3

s. 16(b)(ii)

Records relating to law enforcement are exempt from disclosure if

their disclosure would, or could reasonably be expected to affect the

trial of any person or the adjudication of a particular case.

1

s. 16(c)

Records relating to law enforcement are exempt from disclosure if

their disclosure would, or could reasonably be expected to disclose,

or enable a person to ascertain, the existence or identity of a

confidential source of information, in relation to law enforcement.

1

s. 16(d)

Records relating to law enforcement are exempt from disclosure if

their disclosure would, or could reasonably be expected to reveal

lawful methods or procedures for preventing, detecting, investigating

or dealing with matters arising out of breaches or evasions of the law,

where such revelation would, or could be reasonably likely to,

prejudice the effectiveness of those methods or procedures.

1

s. 16(f) Records relating to law enforcement are exempt from disclosure if

their disclosure would, or could reasonably be expected to jeopardize the security of prison. security of prison.

s. 17(a)

An official record is exempt from disclosure if it would be privileged

from production in legal proceedings on the ground of legal

professional privilege.

12

s. 17(b)(i) An official record is exempt from disclosure if the disclosure thereof

would constitute an actionable breach of confidence. 7

s. 17(b)(iii) An official record is exempt from disclosure if the disclosure thereof

would infringe the privileges of Parliament. 1

s. 18(1)

An official record of a type specified in subsection (2) is exempt from

disclosure if its disclosure or, as the case may be, its premature

disclosure would, or could reasonably be expected to, have a

substantial adverse effect on the Caymanian economy, or the

Government’s ability to manage the economy.

1

s. 19(1)(a)

Subject to subsection (2), a record is exempt from disclosure if it

contains opinions, advice or recommendations prepared for

proceedings of the Cabinet or of a committee thereof.

2

s. 19(1)(b)

Subject to subsection (2), a record is exempt from disclosure if it

contains a record of consultations or deliberations arising in the

course of proceedings of the Cabinet or of a committee thereof.

4

s. 20(1)(b)

A record is exempt from disclosure if its disclosure would, or would

be likely to, inhibit the free and frank exchange of views for the

purposes of deliberation.

2

s. 20(1)(c) A record is exempt from disclosure if it is legal advice given by or on

behalf of the Attorney General or the Director of Public Prosecutions. 12

s. 20(1)(d)

A record is exempt from disclosure if its disclosure would otherwise

prejudice, or would be likely to prejudice, the effective conduct of

public affairs.

1

s. 21(1)(a)(ii)

Subject to subsection (2), a record is exempt from disclosure if its

disclosure would reveal any other information of a commercial value,

which value would be, or could reasonably be expected to be,

destroyed or diminished if the information were disclosed.

3

s. 21(1)(b)

Subject to subsection (2), a record is exempt from disclosure if it

contains information (other than that referred to in paragraph (a))

concerning the commercial interests of any person or organisation

(including a public authority) and the disclosure of that information

would prejudice those interests.

2

s. 23(1)

Subject to the provisions of this section, a public authority shall not

grant access to a record if it would involve the unreasonable

disclosure of personal information of any person, whether living or

dead.

57

s. 24(a) A record is exempt from disclosure if its disclosure would, or would

be likely to endanger the physical or mental health of any individual. 1

TOTAL 123

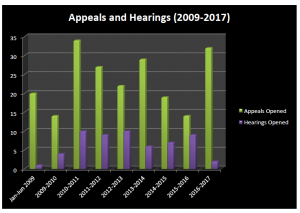

Appeals and hearings (2009-2016)

An applicant may appeal any perceived infringement of the FOI Law by a public authority to the

Information Commissioner, as long as the other means of redress have been exhausted. The most

common reason for appealing is the denial of a request for access by government, but appeals may

also be raised for timeline violations or other procedural infringements.

From 2009 to the end of June 2017 the ICO received some 210 appeals, of which 59 progressed to a

formal hearing before the Commissioner. Of these, respectively 32 appeals and 2 hearings were

initiated in the 2016/17 year. This is the second highest number of appeals ever received at the ICO

and an unusually low number of hearings. We believe the low number of hearings was at least in

part due to higher success rate in our informal resolution process.

Appeals and Hearings (2009-2017)

Appeals Opened

Hearings Opened

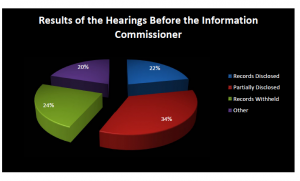

As of 30 June 2017, the Information Commissioner had concluded 55 formal Hearing Decisions.

Previously the outcomes of these decisions were evenly balanced between disclosure and non-

disclosure, while about one in three decisions resulted in partial access being provided. As with last

year the trend continues to shift slightly, with more decisions resulting in partial access being

ordered.

For more information visit www.infocomm.ky

Please see all attachments for figures