Cayman Premier Panton responds to Animal Welfare Concerns

Grand Cayman − Thursday, 9 February 2023

Premier Wayne Panton, MP, JP, as of today, 9 February 2023, has responded to the open letter from the Cayman Islands Humane Society dated 6 February 2023 in relation to the National Conservation (Alien Species) Regulations, 2022 (“The Regulations”).

The Regulations gazetted on 3 November 2022 provide a prohibited species list, outline the distinctions between domestic and feral animals, and further define the procedures and allowable actions to control feral animals and other alien species to reduce the threat to our native species.

Government acknowledged its support of spay and neuter programmes, but in light of extensive scientific evidence and literature, the Premier also acknowledged that Trap, Neuter, Release (TNR) programmes are not a feasible way to address the overpopulation of feral cat colonies across the Cayman Islands:

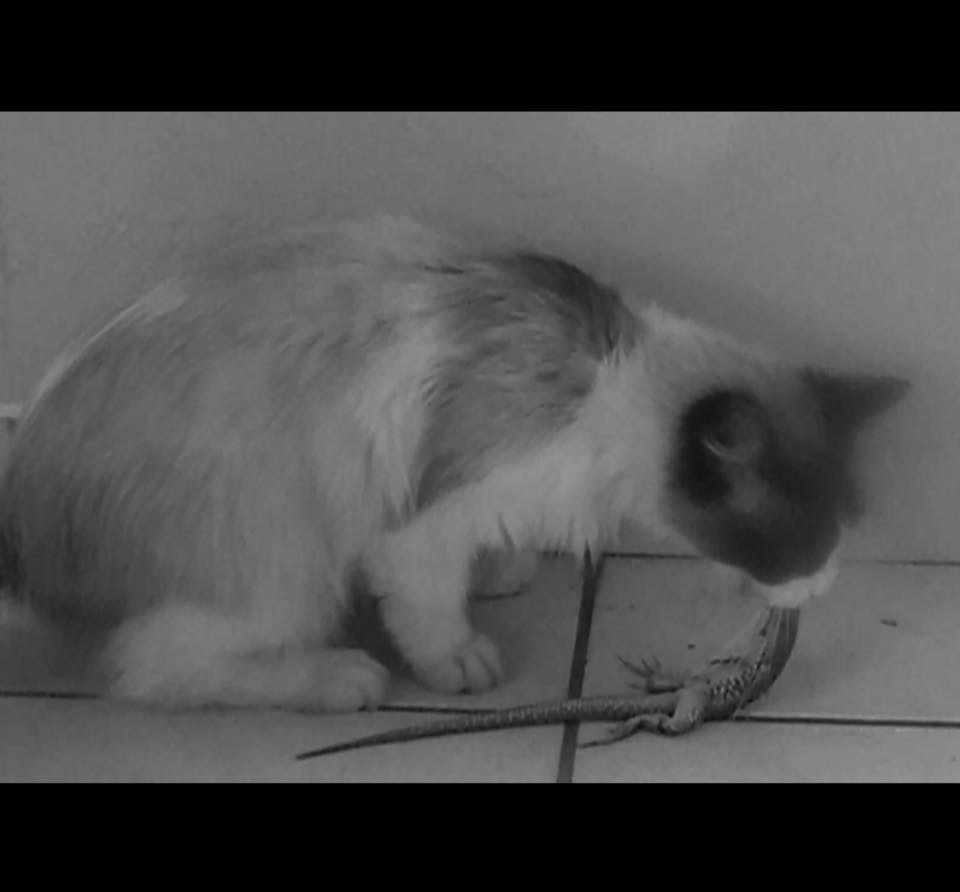

“Of the 129 feral cats captured since 2007, only seven feral cats (two in 2007 and five in 2023) were spayed/neutered. This is a very strong indication that the TNR efforts in Little Cayman have not penetrated the broader feral population of cats there, leaving those animals to not only predate on the young of several regionally and internationally important species, driving their populations into drastic declines, but to also live short and miserable lives in the wild, which raises several serious animal welfare issues. It is for these reasons that the Government will not entertain the application of TNR as a population control method.” said Premier Panton.

Visit GOV.KY to read the full letter from Premier Panton.

For more information on the National Conservation (Alien Species) Regulations, 2022, visit conservation.ky.

9 February 2023

Cayman Islands Humane Society 153NorthSoundRoad

George Town. PO Box 1167 Grand Cayman, KY1-1102

RE: NATIONAL CONSERVATION (ALIEN SPECIES) REGULATIONS 2022

Dear Cayman Islands Humane Society,

Thank you for your open letter expressing your organisation’s concerns about the National Conservation (Alien Species) Regulations, 2022 (“the Regulations”).

As the longest serving local animal welfare non-profit organisation and Grand Cayman’s sole animal We appreciate the efforts of the Humane Society to protect, save, and regime unknown animals in

the community. Equally, we appreciate your efforts to educate and promote animal welfare and responsible pet ownership over the years, efforts which include “combatting pet overpopulation and protecting our threatened ecosystems” as stated on your website.

The Alien Species Regulations came about because the passage of the National Conservation Act (NCA), 2013 charged the National Conservation Council (NCC) with various functions, including the following:

(k) develop criteria for determining whether wild populations or proposed introductions of alien or genetically altered species might cause harm to any of the natural resources of the Islands and procedures for for regulating and controlling such populations and introductions

They were drafted to clarify the means by which the NCC would set out to fulfill its obligations under (k), above. Despite providing mechanisms for the control and management of invasive alien species, it is clear from the Regulations that their primary purpose is to prevent the establishment of invasive species in the first place. Importantly, they do not directly relate to animal welfare, which is dealt with under the Animals Act (2015 Revision). That is not to say that there is anything in the Regulations

which regresses animal welfare inour Islands as you suggest.

The Regulations are therefore supported by international organisations such as the Royal Society for the Protections of Birds (RSPB), as they too understand the compelling scientific evidence from around the world documenting the devastating impact of invasive species such as feral cats on the vulnerable native species and habitats ofsmall islands. This is why they are currently working on thesevery issues in the Sister Islands under the auspices of a Darwin Plus grant with our own Department of Environment.

The alarm over the impact offeral cats on our native species was sounded many years ago. Since 2007, a total of 129 feral cats have been trapped and euthanised on Little Cayman: 29 in 2007, 24 in 2018, 35 in 2022 and 41 in 2023. The Do also invited your organisation’s volunteer Operations Manager to observe all aspects of the June 2022 trapping operation, in order to verify that feral cats were treated humanely. No communication was received from you alleging inhumane treatment or expressing any animal welfare concerns at that time.

As you will also be aware, these Regulations do not herald the trapping and potential culling of feral cats for thefirsttime. The Humane Society, together with Feline Friends, specifically initiated litigation

in February 2018 to prevent the culling of cats on Little Cayman at that time. Your position, then, was that the actions of the Government agencies involved was unlawful as the legal framework to properly authorise the management of alien orinvasive species did not exist. Iam keenly aware that, ultimately almost four years involving many hours of face-to-face discussions and written exchanges of views with your organisation, led to a negotiated settlement of the litigation which allowed the Government to proceed with the trapping of feral cats and the promulgation of these Regulations. Notably, advice received from you as a member of the Department of Agriculture’s Animal Welfare Committee helped to inform the development of the Regulations. Therefore, it is unfortunate that you have deliberately framed the Regulations as something that blindsided your organisation.

Turning now to the issue of Trap-Neuter-Release (TR): the prohibition of which appears to be the crux of your concerns. The peer-reviewed scientific literature is quite clear that T R does not work as

a method of reducing feral cat populations. Additionally, the scientific literature confirms that globally, cat populations have been estimated to consume hundreds of millions of native animals each year. On

islands, where most species have evolved without feline species present, the impacts of feral cat predation has resulted in direct extinctions of mammals, reptiles and birds.

Feral cat impacts on several key native and endemic species are extremely worrying at the local level,

as indicated by data collected by the Department of Environment. This raises concerns about local

species extermination and the need to engage in costly and resource-intensive, long-term recovery

programmes for species. Our own data also show that the trapped and euthanised feral cats are in an

appalling state of health. They are infested with roundworms and tapeworms, have broken teeth,

lacerations and sores, and nasal secretions which indicate viral infections. Although w e were unable to test for feline aids and feline leukemia in the field, it is widely documented that feral cats also suffer

from and carry thesediseases, as well as others which can spread to other animals (including pet cats) and humans.

Of the 129 feral cats captured since 2007, only seven feral cats (two in 2007 and five in 2023) were spayed/neutered. This is a very strong indication that the TNR efforts in Little Cayman have not penetrated the broader feral population of cats there, leaving those animals to not only predate on the young of several regionally and internationally important species, driving their populations into drastic declines, but to also live short and miserable lives in the wild, which raises several serious animal welfare issues. It is for these reasons that the Government will not entertain the application of T R as a population control method.

Finally, on to the issue ofpenal provisions. First, it is important to note that there is no specific offence of feeding cats and chickens, but a general prohibition on feeding alien species or genetically altered species in the wild. Section 18 of t h e Regulations provide a graduated penalty scheme: a Cease and Desist letter for a first time offence; a fine ofu p to $5,000 for a second offence and the application of the penalty provision inSection 38 ofthe National ConservationAct for a third offence. The provisions of Section 38 oft h e Act are an omnibus provision which apply to a wide range of offences under the Act, and ajudge will determine the appropriate sentence based on all of the circumstances surrounding the offence and judicial sentencing guidelines, as is the case now for someone prosecuted under the Act for violating catch limits or closed seasons for species such as conch or lobster. In retrospect, it is regrettable that your legal advisors could not provide you with clarity regarding the actual provisions of the legislation as a way to prevent sensational headlines and continual misinformation dissemination.

Having cared for four dogs (three of whom arerescues), one cat (also arescue)and one parrot, among others over the years, I understand how emotionally charged and sensitive this subject can be. Despite this, we must make hard decisions in order to protect our threatened endemic species that I certainly do not take pleasure from. In the words of a former colleague, extinction is forever, and that’s not a price that can be paid for the sake of today’s and tomorrow’s generations, whose interests I will unabashedly defend.

To protect native wildlife we need attitudestowards responsible pet ownership (i.e. keeping your pets

on your property) to change and an effectiveferal cat population control program toreduce the threats

they pose to our endangered species. I sincerely hope that the Humane Society would be open to

constructive dialogue with the Cayman Islands Government on these issues. We al seem to have the

same expressed objectives, and should together seek ot achieve a more sustainable future for our ecosystems and our beloved Cayman Islands.

Click here to read the full address on GOV.KY.