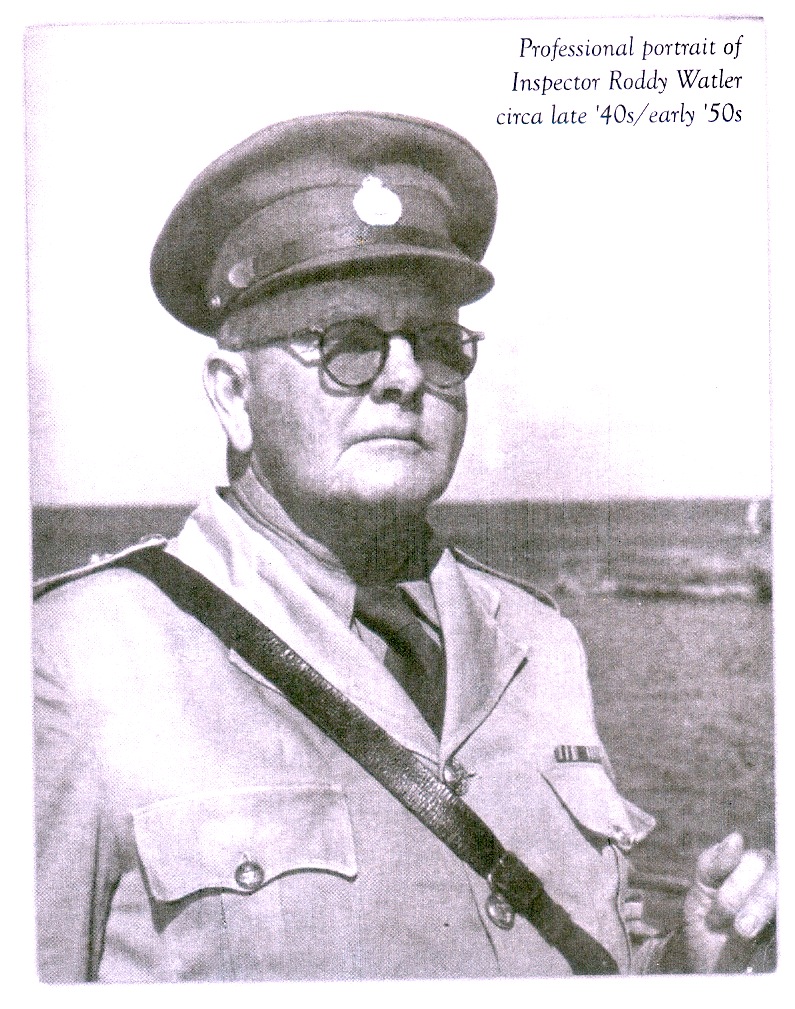

Cayman’s German Spy – In Roddy Watler’s Own Words

By Georgina Wilcox

I have to thank Terri Merren for taking much, much time to transcribe the original audio tapes (we do have the same copy given to us by Grandson Gregory Merren – Terri’s wife) and saving all of us here a lot of work.

Terri produced a most beautiful book transcribed from these tapes full of photographs – most from the family archives.

The book is called “Roddy Watler – In His Own Words” Sub-titled “Memoirs of a Caymanian legend”.

Why there is no mention of Roddy, who was Chief of Police and Captain of the Home Guard (2nd WW), only two of the many posts he held, is a mystery? A HUGE mistake by the very body employed to preserve our history and oversee the editing the history book. Joan (Roddy’s youngest daughter) is convinced it was done deliberately. I can concur with that as the history book has a whole section devoted to the Home Guard, mentioning names but omitting Roddy’s – who was the Captain!

Anyway, I will save that for another story.

In Colin Wilson’s Award Winning Stage Play – “Watler’s War” he introduced the story of the German Spy but the happenings surrounding it were fictitious. Joan, however, witnessed the arrest when she was watching un-noticed up in a tree when she was a little girl.

Because members of the immediate family of the spy (he married a Caymanian) are still alive, the Spy’s name has been redacted and is referred to as “the German spy” or “he”.

Thank you again Terri.

In his (Major Joseph Rodriguez – Roddy – Watler) own words:

THE GERMAN SPY

In 1939, we had living very near to my compound here a nextdoor neighbour – the celebrated German spy. But, before ’39, I would say about ’37 and ’38, two boats came out here from Germany and took [him] on board and went out to the Gulf of Darien. That boat was tied up near to the Panama Canal. [The German spy] came back to the island and some of the crew went home to Germany.

A year later, another boat from Germany came in and the mate on the first boat returned to the island here as mate on the SteHa – another German boat. We went on board – Mr. Ernest Panton [who] was Immigration Officer and myself. We met the captain and he told us that he had spent 17 years in the Caribbean. He knew the Caribbean from A to Z, and he was very glad that he came here but he says, “One thing I have found out since I left Germany (they sailed from Potsdam) that [he, the spy] is a Jew and we do not want anything more to do with him. I says, “Well, I don’t know what he is but I know that he lives quite near to me because he married a girl (my wife’s first cousin right over there) and that’s where he lived. But he says, “I will try to get rid of him the best I know how. I will go and see his wife,” he says, “and I will give her a little bit of money, and I will not take [him] on this trip with me.” Well, I was on board the SteHa (she was a motor vessel) in the harbour, and he showed me all the gadgets he had on board, how to get the depth of water from a cartridge and drop it and it’d explode and it will tell you on the tail there what the depth [is] and all that kind of stuff.

And everything to him was “the Fuhrer.” We drank a couple of beers aboard there and “Hail, Fuhrer!” Every time he drank, it was “Hail the Fuhrer.” And he told us, he says, “If you and Mr. Panton would like to go to Germany,” he says, “I’ll give you a ticket right now. It won’t cost you a penny. Ohhhhh,” he says, “you’ll see the Autobahn, the beautiful highways – five hundred feet wide. Oh,” he says, “you’ll see everything that you want to see.” Of course, war hadn’t broke out yet, you know. That was the beginning. That was in ’39.

So, we had here then Commissioner Cardinall who could speak … he was educated at the University of Heidelberg in Germany and he spoke better German than [this German spy] did, and up at Government House over a few bottles of Rhine wine, [the spy] would tell him anything. [He] would tell him that he was going to be Commissioner of the Cayman Islands when war broke out. He told him that war was pending, it was near at hand and he was here to take over the island when war broke out. So the commissioner always instructed me to keep an eye on [him] but never to touch him until I notified him, as he knew himself that war was coming. So, as he lived right in behind me here, I used to go to my backyard and that brought me up to where his room was and, one morning – I think it was in June in 1939 -I heard him. When I got up to my backyard, I heard him say to his wife, “Get ready. Kill yourself this morning. I kill everybody in the house today.” Well, I took my time in coming back because if I had’ve rushed, it might’ve caused him to think that I was coming at him, you see?

So, in coming back down to my house, his mother-in-law said to me, she says, “Mr. Roddy, you heard what that old devil said?” I said, “Yes, I heard.” And, just about that time, two youngsters (his two brothers-in-law – I suppose they were 16 and 18) came around from the south-end of the house buttoning up their boots on the front step and they says, “Cousin Roddy, business going to pick up here in a minute.” And, just about then, he swung around the house with a Collins machete and caused the two boys to bolt/to run. Well, I came back to the house then to look for my revolver but, having so many children around the place, my wife had to keep on moving it – hiding it to keep it out of their reach. I couldn’t find it! So, I went out to the corner there and I met several people there, and one of the boys had a good club. And I says, “Let me have the club.” So, I took the club and I went on up to the house and the wife said to me … She was crying and moaning [and] she said to me, “He’s got a machete in there and a dagger.” So I went in the room and took the machete away from him but I didn’t see the dagger. I couldn’t find the dagger. So I left him there then in the house and I went to Government House and reported to Commissioner Cardinall what had taken place, and he instructed me to have him arrested. I came back and, by the time I got back to the house, he had gone into the hinterland of the mangroves over here, in hiding. Well, I went up there – all the way up – but I couldn’t find him so I put a chap up in a tree. I says, “You watch the backland for me and, when you see him coming out, you come and let me know.” I came back home and was getting my coffee and had got my gun when the chap came and said, “Mr. Roddy, [he’s] coming out.” So, I went on up the trail and I saw him coming.

And, when about 50 to 60 feet away, I ordered him to ‘hands up.’ I pointed the gun at him and I says, “Hands up!” and he throwed his two hands up and, when I got up to him, the dagger was in his belt in front, and I jerked it out and put him ahead of me. He was a big fat man – about 250 pounds – and he had walked a long distance and he was pretty groggy. When I got him back to the house over here, passing the house, he says, “I want water.” And I stopped in and asked his father-in-law to give me some water. The old man brought out an enamel pitcher of water. And I knew the ‘water trick’ that he would either throw that water in my face and grab for my gun, or else he would hit his father-in-law with the pitcher. So, I was standing firm in case of an attack. So, I knew that he would have to finish drinking the water at just that time because he had drunk a lot. And, as he went to dish the water at the father-in-law, I struck him under the chin and I says, “Get outta here!” I says, “What’re ya thinkin’ about?” He says, “Ah!” He says, “That’s my gun!” I said, “By God, it’s not your gun but I’ll put it in you!” I said, “If you ain’t careful, I’ll shoot you!” He says, “That’s my gun you got there.” I said, “No, no, you make a mistake. This is not your gun.” I took him from there and I got him to the police station and locked him up and, after certain preliminaries had been forwarded to Jamaica, we got instructions to send him on to Jamaica.

Well, we had a Sergeant of Police here. He was a big fella. He had served three and a half years in Mesopotamia as a soldier in the first World War. So, the commissioner directed me to prepare the Sergeant of Police to take [the German spy] down to Jamaica. The boat was leaving on a Friday and, on the Wednesday, the sergeant began to drink, and he was a heavy drinker. Thursday, I went to the commissioner’s office and I says, “Your Honour, if you want [this man] to reach Jamaica, you better let me take him, sir. The sergeant is drinking and, if he leaves here under the influence of liquor, there’s no telling what might happen at sea. He says, “Right, Roddy. I’ll send a wire to Jamaica that you are coming. And leave the sergeant here.” I went back down to the police station and I saw the sergeant. I says, “Sergeant, the commissioner has changed the programme. I’m taking [the prisoner] to Jamaica instead of you.” He said to me, he says, “Oh! You? You wouldn’t get even as far as Cayman Brae.” “Well,” I says, “under the circumstances, you wouldn’t get even that far. Anyway, I’m taking him!” I went into the jail and went into [the prisoner’s] cell and I said to him, I says, “I’m taking you down to Jamaica tomorrow evening and, from there, I’m sending you out to Costa Rica.” “Ah!” he says, “Good God, that’s where I want to go!” He said, “That’s where my people is.” He says, “I go. You have no trouble with me.” That was a brainwave, you see?

So, I got [him] all dressed up the next day – the next Friday evening – and placed him on board the Cimboco with my corporal, Nixon, and myself. Just before leaving the dock, he said to me, “Spect,” he says, “you got anything to drink?” I says, “No, I haven’t got anything but if you want something, I’ll send up and get it.” So, one of his brothers-in-law was right present. I says, “Son, run up and tell Captain Ben, the barkeeper, to send me a bottle of whiskey and a couple of ginger ales.” The boy came back with the whiskey and ginger ale and, just as we pulled out from the dock, backing out, I opened the ginger ales, handed one to the corporal and one to [the prisoner]. The corporal drank his. He gave me the pint and I threw it through the porthole. I noticed [the prisoner] drank his and kept the pint so the thought flashed into my head, “What a lick he will give me tonight with that pint.” Just then, he spoke t~ me. He says, “Spect,” he says, “you think I keep this pint and hit you with it tonight, no?” I says, “Hell, no.” I says, “Look at what I got here.” And I lifted my revolver from under my leg and I said, “This protects me. You got the pint. I’ve got this!” I says, “I wasn’t thinking that at alL” He says, “Aye,” he says, “I’ll tell you what I keep it for.” He says, “I keep this and put my cigarette ashes in it.” And he took out his pillow from under his head and he laid flat. His belly was up so big, and when he would smoke a cigar down to say three inches, he would rise and shove the ashes into that pint bottle and snip it off and, when we got to Port Royal, he had that pint filled with ashes.

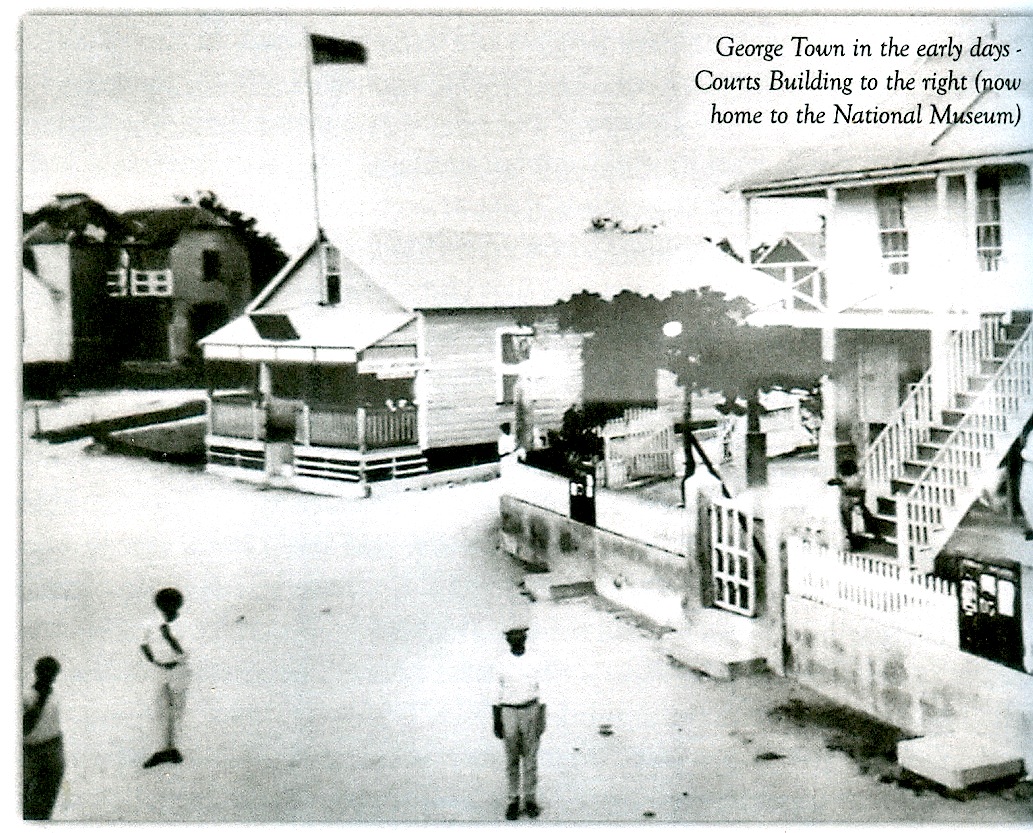

At Cayman Brae (the boat stopped near Cayman Brae, you see and), he said to me, he says, “You taking me to the asylum?” “Ah,” I says, “What about asylum? Where you heard about asylum? You dreamt it?” “Oh,” he says, “I thought you take me to the asylum.” I says “It’s just what I told you. You goes to Costa Rica.” “That,” he says, “that’s very good. Good.” Well, we went on and up along the coast of Jamaica. Sometimes, we were very close to land. And when he went to the toilet in the night, the corporal went up with him and I went to the corner where I could watch him if he come through the window out on the deck. So, one night, he saw me. And, when I went George Town in the early days Courts Building to the right (pow home to the National Museum), back to the room he says, “Hey, you think I jump overboard?” I says, “Well, you wouldn’t last long if you went overboard.” I says, “The sharks is over there waiting for you.” “Aye,” he says, “I don’t give a damn.” He says, “If they cut the head off,” he says, “but not the foot.” He says, “I go.” He says, “I finish. They cut the head off,” he says, “I finish.”

Well, we went on and we arrived at Port Royal where we were met by the Immigration officers and the doctor examined the papers and he said to me, “What about this man?” Well, I couldn’t say anything. I had to muzzle my information in his presence. I said, “Doc, just what you see on the papers is all I’m prepared to say.” And he took stock of that and left it at that.

We arrived in Kingston and I was very happy when I saw the police wagon with two constables and an Inspector of Police. I was a happy man. I had got my man safely into Kingston. He was taken to the lunatic asylum. There he remained until the end of the war as a very terrible, crazy man. The second engineer from the Cimboco used to take a few necessities from his wife here to him in the asylum. And he reported that he had to put a net over him to get near him; he was so badly insane.

But weeks after the war was finished, (he) became sane and he was shipped back to Germany as a displaced person. We never heard anything more from him. His wife had a son and that boy has growed up now to be a man, and he’s been to Hamburg and Potsdam and several ports in Germany, and he could never find any trail of him at all. The boy is now an engineer in America. Now, that ends the [German spy] affair.