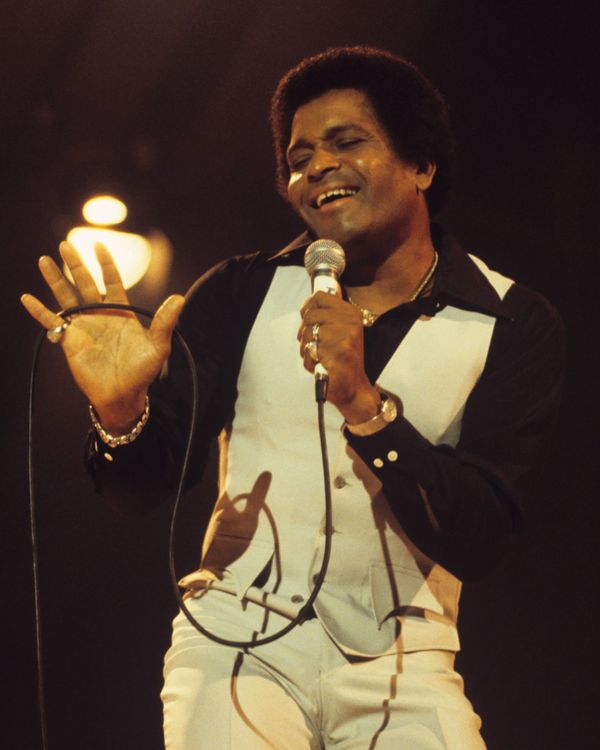

Charley Pride deserved better than what Country Music could ever give him

By Andrea Williams From Vulture

If he hadn’t been sent home after attempting to crash the 1963 Mets spring training in Clearwater, Florida, if his effort to cobble together a professional baseball career hadn’t finally failed, Charley Pride may have never ended up in Nashville.

Sure, he’d already landed several country gigs in Big Sky country, driving up to 180 miles round trip to play shows and make some extra cash after working his day job at a Montana smelter. He’d even been fortunate enough to play on the same bill as country stars Red Sovine and Red Foley. Sovine was so impressed with Pride that he encouraged him to go to Nashville, to pay a visit to the folks at Cedarwood Publishing. “I don’t care what color you are,” he said.

It’s not enough to say that he was first, that he was great, that he was an inspiration to countless Black men and women, boys and girls, who also wanted to believe that they could eke out a career in country.

In the aftermath of the December 12 announcement that Charley Pride succumbed to COVID-19 at the age of 86, it is difficult to consider his life and legacy as a country-music icon without considering the environment that birthed his career. He didn’t just show up in Music City as a Black man wanting to sing country music; he arrived in the midst of the ’60s Civil Right Movement, a movement that, in many ways, found its epicenter in Nashville. Students from the city’s HBCUs had launched formal sit-ins to desegregate Music City’s lunch counters in February 1960; two months later the home of civil rights attorney Alexander Looby was bombed, injuring students at nearby Meharry Medical Center and leading to the organization of a march to Nashville’s City Hall. By May of that year, Nashville had officially desegregated public facilities, even as its thriving music industry remained divided by harsh color lines.

The CMAs should’ve awarded Pride well before 2020, before a raging pandemic would threaten — and ultimately end — his life.

It is impossible to consider Jackie Robinson’s legacy without careful analysis of his pioneering efforts, and so Pride’s must be given similar treatment. It’s not enough to say that he was first, that he was great, that he was an inspiration to countless Black men and women, boys and girls, who also wanted to believe that they could eke out a career in country. Those things are true, but for the purposes of proper, honest reflection — and with respect to the Black folk who never really had a chance to follow Pride to the top of the country charts — we must also consider what Pride wasn’t. Much in the way Major League Baseball’s restrictions prevented Robinson’s signing and success from bringing a flood of Black talent into the Majors, country music’s still-present barriers have kept Pride’s achievements from triggering an influx of new Black talent. He may have been an icon, a legend, and a hero, but a marker of things to come he was not. As Rucker moves into his position of elder statesmen, Jimmie Allen and Kane Brown are the sole representatives of Black male talent welcomed into the country mainstream. Representing women, Mickey Guyon stands alone and still criminally without a full album released, despite being signed by Capitol Nashville in 2011.

For more on this story go to: VULTURE

EDITOR NOTE: Charley Pride and his Band performed in the Cayman Islands for Pirates Week in 199o’s. The following year just the Band appeared.