Coronavirus: Are we getting closer to a vaccine or drug?

By James GallagherHealth and science correspondent From BBC

Coronavirus is spreading around the world, but there are still no drugs that can kill the virus or vaccines that can protect against it.

So how far are we from these life-saving medicines?

What sort of progress is being made

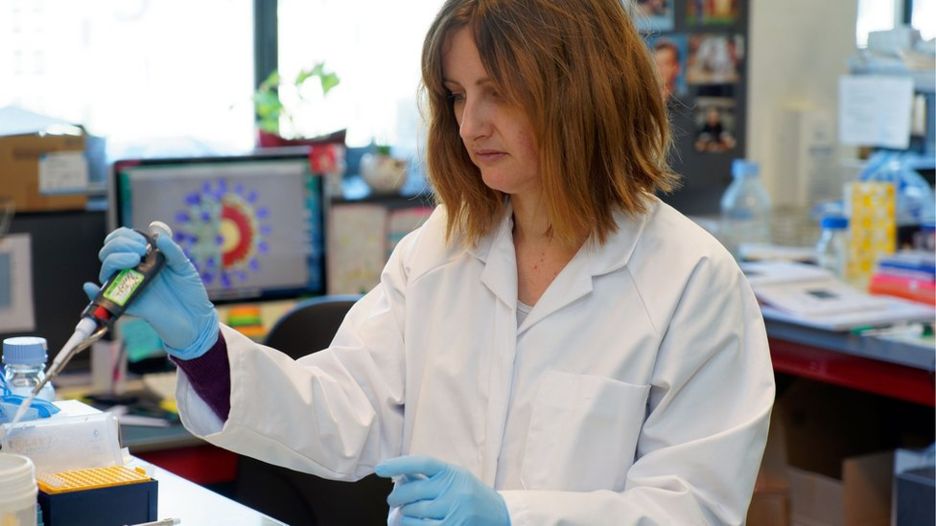

Research is happening at breakneck speed, and there are more than 20 vaccines currently in development. Among those under way at the moment are:

- The first human trial for a vaccine was announced last month by scientists at a lab in the US city of Seattle. They have taken the unusual step of skipping any animal research to test the vaccine’s safety or effectiveness.

- Australian scientists have begun injecting ferrets with two potential vaccines. It is the first comprehensive pre-clinical trial to move to the animal testing stage, and the researchers say they hope to move to the human testing stage by the end of April.

Tests like these are taking place much quicker than would normally be the case, and some are using new approaches to vaccines. It follows that there are no guarantees everything will go smoothly.

But even if these – or any other tests – do prove successful, it’s not expected that manufacturers will be able to produce a mass-produced vaccine until the second half of 2021.

Remember, there are four coronaviruses that already circulate in human beings. They cause the common cold, and we don’t have vaccines for any of them.

What do I need to know about the coronavirus?

- ENDGAME: When will life get back to normal?

- EASY STEPS: What can I do?

- A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

- MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

- VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

Could existing drugs treat coronavirus?

Doctors are testing current anti-viral drugs to see if they work against coronavirus. This speeds up research as they are known to be safe to give to people.

Trials are taking place in England and Scotland on a small number of patients with an anti-viral called remdesivir. This was originally developed as an Ebola drug, but also appears effective against a wide variety of viruses.

Similar trials have already been carried out in China and the US, and results are expected in the next few weeks.

There was much hope that a pair of HIV drugs (lopinavir and ritonavir) would be effective, but the trial data is disappointing.

They did not improve recovery, reduce deaths or lower levels of the coronavirus in patients with serious Covid-19. However, as the trial was conducted with extremely sick patients (nearly a quarter died) it may have been too late in the infection for the drugs to work.

Studies are also taking place on an anti-malarial drug called chloroquine. Laboratory tests have shown it can kill the virus, and there is some anecdotal evidence from doctors that it appears to help. However, the World Health Organization says there is no definitive evidence of its effectiveness.

Would a vaccine protect people of all ages?

It will, almost inevitably, be less successful in older people. This is not because of the vaccine itself, but aged immune systems do not respond as well to immunisation. We see this every year with the flu jab.

Will there be side effects?

All medicines, even common pain-killers, have side effects. But without clinical trials it is impossible to know what the side effects of an experimental vaccine may be.

This is something on which regulators will want to keep a close eye.

Who would get a vaccine?

If a vaccine is developed then there will be a limited supply, at least in the early stages, so it will be important to prioritise.

Healthcare workers who come into contact with Covid-19 patients would be at the top of the list. The disease is most deadly in older people so they would be a priority if the vaccine was effective in this age group. However, it might be better to vaccinate those who live with or care for the elderly instead.

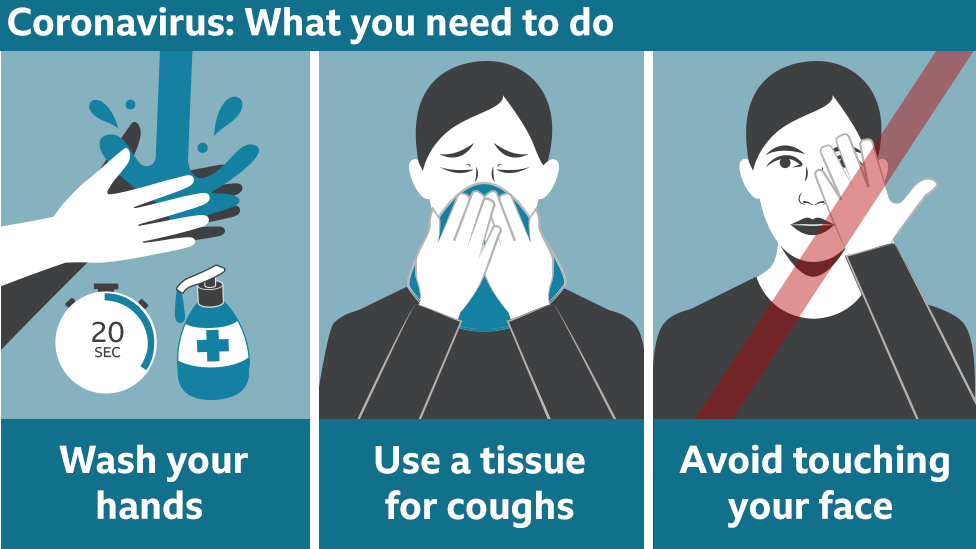

Until a vaccine or treatment is ready what can I do?

Vaccines prevent infections and the best way of doing that at the moment is good hygiene.

If you are infected by coronavirus, then for most people it would be mild and can be treated at home with bed-rest, paracetamol and plenty of fluids. Some patients may develop more severe disease and need hospital treatment.

How do you create a vaccine?

Vaccines harmlessly show viruses or bacteria (or even small parts of them) to the immune system. The body’s defences recognise them as an invader and learn how to fight them.

Then if the body is ever exposed for real, it already knows how to fight the infection.

The main method of vaccination for decades has been to use the original virus.

The measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine is made by using weakened versions of those viruses that cannot cause a full-blown infection. The seasonal flu jab is made by taking the main strains of flu doing the rounds and completely disabling them.

The work on a new coronavirus vaccine is using newer, and less tested, approaches called “plug and play” vaccines. Because we know the genetic code of the new coronavirus, Sars-CoV-2, we now have the complete blueprint for building that virus.

Some vaccine scientists are lifting small sections of the coronavirus’s genetic code and putting it into other, completely harmless, viruses.

Now you can “infect” someone with the harmless bug and in theory give some immunity against infection.

Other groups are using pieces of raw genetic code (either DNA or RNA depending on the approach) which, once injected into the body, should start producing bits of viral proteins which the immune system again can learn to fight.

For more on this story go to: https://www.bbc.com/news/health-51665497