Disaster clean up

Who cleans up after hurricanes, earthquakes and war?

Who cleans up after hurricanes, earthquakes and war?

By Lucy Rodgers From BBC

Natural disasters can reduce entire cities to rubble, leaving streets littered with debris, bodies and toxic material. Modern warfare’s devastation also brings the hidden dangers of unexploded weapons, landmines and booby traps. Who clears up the wreckage of natural and man-made catastrophes and where does it go?

Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria battered the Caribbean and the southern US throughout the last two months, killing dozens, shattering lives and leaving a trail of destruction behind them.

Puerto Rico has been ravaged by hurricanes

Then, in the middle of September, a 7.1 magnitude earthquake hit central Mexico causing dozens of buildings to collapse in Mexico City and beyond, trapping people beneath broken concrete and twisted metal.

Continuing conflicts in the Middle East have also left thousands dead and major cities destroyed. Much of Mosul in Iraq has also been reduced to rubble and huge swathes of Syria’s Homs and Raqqa and the World Heritage City of Aleppo have been flattened.

The latest analysis of Aleppo, just completed by the UN’s satellite programme, UNOSAT, suggests more than 7,000 sites have been damaged in the Old City alone. Some witnesses describe rubble and wreckage piled to the top of buildings.

Aleppo’s Old City has been devastated

All these natural and man-made disasters have left behind millions of tonnes of debris. What will happen to it?

Dumping it in landfill is not the answer

In the midst of post-emergency chaos, when the piles of damaged or waterlogged remains of communities line the streets, survivors and anyone else on hand tend to begin the process of moving debris.

But amid the shock and devastation, what does and what should happen next are often two very different things, says Martin Bjerregaard, director of Disaster Waste Recovery, and Aiden Short, director of Urban Resilience Platform – two disaster specialists who have worked all around the world in the aftermath of storms, earthquakes and wars.

You can’t just tip debris in a hole

Martin Bjerregaard, director, Disaster Waste Recovery

In the haste to recover, politicians often resort to quick-fix solutions that have serious repercussions, explains Mr Bjerregaard.

It’s a “really difficult environment to work in”, he says. “But you can’t just tip debris into a hole.”

However, this can be exactly what happens.

After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Louisiana state officials dumped more than 30 million cubic metres (39 million cubic yards) of debris – enough to fill three Superdomes – in local landfills.

New sites were opened – some not adequately lined to prevent toxins leaking into the ground – and much of the dumped waste remained unsorted. Waivers were also issued allowing the dumping of materials not usually permitted at landfill.

The reason such wreckage can’t simply be stuck in the ground is its composition. Although debris varies from crisis to crisis – affected by, among other things, the type of disaster, geography, population density, and how rich or poor the area is – it will almost always comprise a wide range of solid and liquid waste.

Construction materials from damaged buildings, furniture, electronics, trees and other organic matter, industrial materials, vehicles and personal belongings as well as hazardous waste – such as asbestos, pesticides, oils and solvents – could all be left behind.

Dumping such waste is an obvious threat to public health and it is also likely to have an impact on the environment.

Flooding in Havana, Cuba, after Hurricane Irma

In conflict zones, heavy metals from munitions, toxic residues from explosives and booby traps are added dangers hidden in the debris.

This can “complicate waste removal and impede access to affected areas”, says Doug Weir, from the research organisation Toxic Remnants of War.

“Early identification of environmental health risks from conflict pollutants and waste is vital.”

Clearing the debris should be teamwork

This is why it’s essential for authorities to work alongside experts and local people to develop a detailed disposal plan.

In countries with large institutional capacity, such as the US, debris clearance is usually overseen by the federal government and its affiliated institutions alongside state and municipal authorities.

However, in countries without such resources to draw on, or where institutions have been wiped out, the UN and non-governmental organisations usually step in to help on request.

UN guidelines recommend a rapid assessment of damage in the first 72 hours after a crisis hits, with a focus on clearing roads to ensure emergency vehicles can access affected sites. Dealing with dangerous and harmful materials is also a priority – especially in conflict zones.

However, once the immediate dangers are dealt with, a more detailed assessment of the debris and plans for dealing with it are developed.

Debris clean up in Aleppo, Syria

There are two basic approaches that can be adopted, explains Ugo Blanco, the UN Development Programme’s regional adviser for crisis and conflict in Latin America and the Caribbean.

You can bring in heavy machinery and experts, or engage the community and pay them to clear the debris in “cash-for-work” schemes.

Both have their pros and cons, he says.

Machinery is fast, but expensive, while cash-for-work is slower, but has the added advantage of engaging the community and providing livelihoods in the early days following an emergency.

“Instead of waiting for the relief to come, they become actors in the process,” says Mr Blanco.

In reality, he says, when the UN is involved, both approaches are usually combined.

“What we often do is to try to find a good balance, so cash-for-work and machinery, depending on the needs.”

Waste is money. Waste for many is rubbish, but if it’s properly handled it can be a social income.

Ugo Blanco (right), UN Development Programme adviser for crisis and conflict

Disaster debris specialists like Martin Bjerregaard and Aiden Short often get involved in about week two of a crisis, when more detailed debris assessments are required.

They will already have built up a picture of the situation on the ground – the amount of debris, where it is, what it’s made up of and what facilities and equipment will be required to deal with it – from satellite images and other sources to produce “good enough” data. They also use people in the field to verify the information, known as “ground-truthing”.

The pair’s twin organisations then pay their own expenses to enter a disaster zone, before liaising with officials and other agencies, such as the UN, to secure funding and feed into plans for managing the debris longer-term.

They will look at the equipment and facilities required, as well as the people and skills needed to do the job.

Their strategy will depend on the priorities and goals set by the authorities involved – such as speed of clearance, cost, impact on the environment and the employment of local people.

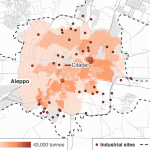

In Aleppo – one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world and Syria’s largest city before the war – the clearance task is enormous.

Analysis by Disaster Waste Recovery suggests there is about 15 million tonnes of debris in the city. If it was to be rebuilt exactly as it was, it would require a staggering amount of building materials – seven times the annual output of all quarries in Syria.

Debris is spread right across Aleppo

Map showing where Aleppo’s debris is located

Source: Disaster Waste Recovery, Urban Resilience Platform

Map showing damage levels in Aleppo’s Old City

Source: Damage assessment by UNITAR-UNOSAT; satellite image Google/DigitalGlobe

This is why, in places like this, debris recycling becomes essential and the choice of strategy crucial. Each option will have a very different impact on the outcome for Aleppo’s people and the environment.

But, to really improve the way disaster debris is managed, specialists and the UN are in agreement that there needs to be a massive shift in the way wreckage from emergencies is regarded.

Instead of seeing it as something to be dumped, it should be viewed as a useful and valuable resource.

“Waste is money,” says Mr Blanco, who has been working for the UN in post-disaster environments for more than 10 years. “Waste for many is rubbish, but if it’s properly handled it can be a social income.”

Building materials can be salvaged and reused when rebuilding structures, others can be recycled – masonry can be crushed and used in road reconstruction. Even fallen trees can be turned into wood chippings and reused.

This focus on recycling not only lessens the burden on disposal facilities and natural resources – often harvested for reconstruction – but also helps provide work for local people and businesses.

The money-saving implications can be huge, says Mr Bjerregaard.

“You’re reducing the cost of the transport of the debris to disposal, you’re reducing the cost of bringing in aggregates from quarries and you’re creating a value from the recycled material, which can feed job-creation, livelihoods and enterprises.”

We needed to remove the debris to forget what had happened and start a new life

Victoria Demera, who helped in the aftermath of a 7.8-magnitude earthquake that hit Ecuador last year

This way of turning a disaster into a vehicle for positive change is what specialists in the field aim for.

Despite the devastating impact of earthquakes, storms and wars, they can, if dealt with correctly, serve to strengthen a community’s resilience in the face of other crises in the future.

“Disasters emphasise the vulnerabilities of the cities, the families and institutions,” says Mr Blanco. “Waste and debris management is just the first stepping stone to more resilient communities, institutions and nations.”

Debris removal develops skills

For Victoria Demera, the devastating 7.8-magnitude earthquake that hit Ecuador last year actually helped her reconnect with her community and develop a career.

She quit her studies to devote herself to post-disaster work in Las Gilces, Manabi province, where 75% of homes were badly damaged.

“We needed to remove the debris to forget what had happened and start a new life,” she says. “The community was in need of work and this gave us more income to rebuild our homes.”

Working as a clean-up brigade co-ordinator helped her develop leadership skills as well as challenge preconceived ideas about women’s roles.

“I have grown as a person and professionally,” she says.

Debris clean up in Homs, Syria

Yet, despite its obvious importance in promoting recovery, debris clearance is almost always underfunded by donors, both at an institutional and individual level. This is because it isn’t an easy sell, unlike prestige projects, such as building schools or libraries, explains Mr Blanco.

“It’s expensive and it’s not like giving a cookie to a child,” he says. “It’s not fancy, it’s not sexy, so we have a lot of trouble getting the funding required to do things properly.”

But with massive debris-clearance operations undertaken following the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004, the earthquake in Haiti in 2010 and a number of disasters hitting in quick succession this year, knowledge and experience is growing in the field.

The technology that allows for efficient data sharing has also improved greatly, providing responders with crucial information early.

Yet the challenge remains to make this count when the next disaster strikes.

“We know what needs to be done,” says Mr Blanco. “The difficulty is making sure that happens. The difficulty is making sure that instead of just getting rid of the debris as quickly as possible, we do it in a sustainable manner, despite that being slower and more expensive.”

The aim?

“Let’s try to do it better next time,” he says.

Credits

Development by Rosie Gollancz, design by Prina Shah.

For more on this story go to: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-d7bc8641-9c98-46e7-9154-9dd6c5fe925e