Do the limbo! How the Windrush brought a dance revolution to Britain

By Judith Mackrell From The Guardian UK

By Judith Mackrell From The Guardian UK

The Caribbeans who answered the call to save postwar Britain sparked a dance explosion. A new show relives those heady days

When the Empire Windrush docked at Tilbury in 1948, the Trinidadian singer Lord Kitchener was among the 492 Caribbean passengers arriving to begin a new life in Britain. Journalists mobbing the Essex docks asked the jauntily debonair Kitch to sing for them and, barely missing a beat, he responded with his newly composed calypso, London Is the Place for Me.

Kitch’s optimistic lyrics embodied the hopes of the estimated 170,000 Caribbeans who would follow him over the next decade or so. They were drawn by the 1948 British Nationality Act, which gave them rights of settlement, and by a huge advertising campaign in which Britain promised excellent jobs and wages to all those who would come to help rebuild the nation after the devastation of war.

“They had a good home in Jamaica,” says Sharon Watson, director of Phoenix Dance Theatre, which has created a new work to mark the 70th anniversary of that first wave of immigration. “But they felt that a call for help had come out from the motherland. They were part of a generation who held England in such high esteem that they believed it was their duty to respond.”

Windrush: Movement of the People is based partly on Watson’s own parents’ journey from Jamaica to Leeds in the 1950s, emphasising the loyalty that motivated them to go through such an upheaval. It felt horribly poignant to Watson that, having set out for the UK with such high-minded hopes, her parents encountered so much cruelty.

The racism of 1950s Britain was brutal, Watson says. “My mother wept and wept once she started telling me about it: ‘When the call came out we answered it. But we arrived to all these notices saying: No dogs, no blacks, no Irish. That really hurt.’” Equally shocking was the standard of living. “My parents thought they would be lush with money. But the wages were so meagre, people were living one family to a room.”

Worst of all perhaps, her mother and father had to come to the UK without their children. It would be nine years before they could afford to fly all five over. So Watson, who was born in Leeds, did not meet her youngest brother until he was 14. Yet for all the grimness of her parents’ initial struggles, Watson has chosen to also focus on the successes they and so many others made of their lives, highlighting the profound ways in which the Windrush generation went on to shape the culture of their new home.

Researching the subject with composer Gary Crosby, Watson was fascinated by the impact Caribbean dance and music made on Britain. Calypso, with its melodious syncopations and witty innuendo, won an enthusiastic audience. In 1957, Harry Belafonte’s recording of The Banana Boat Song (Day-O) reached No 3 in the UK charts. But the early Caribbean arrivals also brought gospel and their own take on country and western. “Everyone in Jamaica used to listen to it on American pirate radio,” says Watson.

The younger immigrants brought the cooler, more politicised music of ska, rocksteady and reggae. As these mixed with the established lingua franca of jazz and R&B, new hybrids began to appear: northern soul, lovers rock, two tone and dub. The music that accompanies the final scene of Watson’s work tells its own story: “There’s some Jim Reeves in there, Louisa Mark, a dub step track, Jocelyn Brown and Amazing Grace.”

Along with the music came the dances: the ska-inspired skanking, for instance, whose rapid footwork and punching arm movements became popular with mods in the 60s. In 1955, Lambeth town hall had done its bit for racial integration by holding a “No colour bar dance” where local white dancers were encouraged to try out the mambo, while their black neighbours experimented with the foxtrot.

Yet what interests Watson is not so much the migration of specific steps to Britain, but the more generalised impact that Caribbean communities made on the nation’s dancing habits. The expense, as well as the cultural awkwardness of dancing in white clubs and dance halls, meant that they often preferred to hold parties in their own confined living rooms.

Watson can still remember the crowded lovers rock and blues parties that became a defining feature of the Jamaican community in Leeds. “They would start very late, at midnight, and go on until the early hours,” she says. “There would be almost no light, a lot of alcohol, probably a lot of smoking, and the space would be so squeezed you’d have people dancing right up against your back.”

These intimate house parties were very different from the public spaces in which the British had habitually danced. But, by the late 60s and 70s, they had become the norm. So too had the rapt, improvised style of movement employed by young white people as they tried to approximate the hip-swaying, loose-jointed, African-inflected influences of the Caribbean.

Watson has referenced some of those influences in her own choreography. But she has deliberately restricted them to a flavour rather than a literal re-creation. “I didn’t want the work to become a history lesson,” she says. “It needs to be theatrical, to connect with the audience.”

Windrush is her first fully narrative work and, while she’s been apprehensive about the challenges of sustaining character and storyline, she’s proud of having engaged with so historic a subject. She has been astonished by the number of people wanting to share their stories, including the granddaughter of the Windrush’s captain. “I feel as though my dancers and I have become part of a landmark event,” she says. “I feel as though I’ve lived every aspect it.”

• Windrush: Movement of the People is at West Yorkshire Playhouse, Leeds, 7 to 10 February. Then touring until 10 May.

Since you’re here …

… we [The Guardia] have a small favour to ask. More people are reading the Guardian than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help. The Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we do it because we believe our perspective matters – because it might well be your perspective, too.

I appreciate there not being a paywall: it is more democratic for the media to be available for all and not a commodity to be purchased by a few. I’m happy to make a contribution so others with less means still have access to information.

Thomasine F-R.

If everyone who reads our reporting, who likes it, helps fund it, our future would be much more secure. For as little as £1, you can support the Guardian – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.

IMAGES:

Street limbo … The Irwin Clement Caribbean steel band in London, 1963.

Eleanor Bull’s costume designs for Windrush: Movement of the People

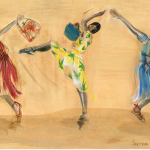

Vanoye Aikens and Katherine Dunham in The Caribbean Dances Show at the Cambridge theatre, London, in 1952. Photograph: AP

For more on this story and video go to: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2018/feb/06/windrush-movement-of-the-people-west-yorkshire-playhouse-jamaica-dance