Evidence mounts of flawed US State Department Caribbean report

WASHINGTON, USA — There is a growing body of evidence that the 2017 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR) published last month by the US State Department’s Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs contains a number of factual inaccuracies in relation to the Eastern Caribbean.

The INCSR covers 87 countries and territories and two regions (The Dutch Caribbean and the Eastern Caribbean) and comprises two volumes: Volume I – Drug and Chemical Control, and Volume II – Money Laundering and Financial Crimes.

One of the expressed purposes of the INCSR is to provide “the factual basis” for the president’s report to Congress on the major drug-transit or major illicit drug producing countries.

However, not only is the INCSR factually incorrect compared to external evidence, it is also internally self-contradictory.

Shortly after the publication of the INCSR last month, the government of Antigua and Barbuda issued a detailed rebuttal of a number of what it described as unsubstantiated misrepresentations made by the State Department in the report.

Earlier this month, the financial services regulator in the Nevis Island Administration (NIA), also refuted claims made in the INCSR as “unfounded and misleading”.

According to the footnote on page 7 of the INCSR Volume II, the report is based upon the contributions of “numerous US government agencies and international sources” and goes on to list some of the agencies that provided such information, including the Departments of Homeland Security, Justice, and Treasury; and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

We accordingly submitted requests under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) for all records relating to any information sought by and/or provided to the Department of State in connection with INSCR 2017 and any requests for such information.

In response, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) (a division of the Department of Justice) has said that they have no responsive records of providing any such assistance to the State Department in relation to the INCSR.

The State Department subsequently attempted to downplay the DEA response on the grounds that “the DEA’s search was limited to a single office within the agency, the DEA’s Office of Global Enforcement Financial Operations Unit, further narrowed to the Operations Division of that specific unit”.

However, the INCSR itself refers specifically to “the DEA’s Office of Global Enforcement/Financial Operations (FO)” in the context of the report on page 11 of Volume II.

The State Department went on to say that within a “majority of the US embassies there is an embedded team of DEA representatives who carry out their mission and mandate in cooperation with the host nation and under the purview of the US ambassador”.

This has been denied by other government sources, who say that, at most, there may be a DEA liaison officer at any given embassy in the region (assuming the position is not currently vacant) and certainly not “a team of DEA representatives”, especially in the Bridgetown embassy in the context of the flawed report in relation to the Eastern Caribbean.

Similarly, although not one of the US government agencies specifically cited by the INCSR (but not excluded either), the Department of Commerce International Trade Administration (ITA) has stated that “after a thorough search, ITA has found no records responsive to your request”.

A major drug-transit country is defined in the INCSR as one: (A) that is a significant direct source of illicit narcotic or psychotropic drugs or other controlled substances significantly affecting the United States; or (B) through which are transported such drugs or substances.

A number of such major illicit drug producing and/or drug-transit countries were identified and notified to Congress by the president on September 14, 2015, none of which were located in the Eastern Caribbean.

Suddenly, however, in 2017, INCSR Volume 1 states on page 151 that Antigua and Barbuda, along with the rest of the Eastern Caribbean, “hosts abundant transshipment points for illicit narcotics” and that “‘go-fast’ boats, fishing trawlers, and cargo ships continue to play major transit roles”.

Specifically, page 152 states that during “the first nine months of 2016, drug seizures in the Eastern Caribbean totaled 1,103.8 kg of cocaine…”

Contrast the reported 1,100 kg of cocaine seized in the “major-transit” Eastern Caribbean with tons of cocaine seized relative to Puerto Rico in just this year alone, as reported by Caribbean News Now:

• 2,000 pounds of cocaine intercepted – January 12, 2017

• Scheme to smuggle “large amounts” of narcotics from Puerto Rico – February 9, 2017

• 1,522 lbs of cocaine seized in Puerto Rico – February 25, 2017

• 4.2 tons of seized cocaine in Puerto Rico – February 28, 2017

• 400 kgs million of seized cocaine in Puerto Rico – March 23, 2017

• 1,608 kgs of cocaine seized off Puerto Rico – March 31, 2017

• 1,320 lbs of cocaine intercepted off Puerto Rico – April 14, 2017

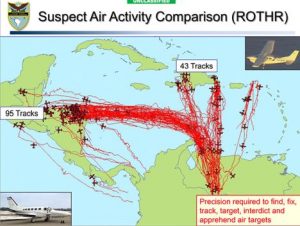

No evidence was provided or any sources cited in the INCSR for the assertions of major drug transshipments in or through the Eastern Caribbean, which are in fact contradicted by other US government data, including radar maps:

The image”suspect air activity” depicts a recent relocatable over the horizon radar (ROTHR) mapping of drugs flights. Conspicuous by their absence from detected suspicious flights on this map are the islands of the Eastern Caribbean

Another online interactive map (drugs.globalincidentmap.com) of major drug interdictions in the Caribbean for the period January 2015 through March 2017 shows just one such maritime interdiction in relation to Antigua and Barbuda and that was a vessel crewed by two Jamaicans.

Also contrast the claim that the Eastern Caribbean is a major transshipment point to the CIA Factbook entry in relation to Antigua and Barbuda (updated January 2017), which states that the country is “considered a minor transshipment point for narcotics bound for the US and Europe” (emphasis added).

In response to a request for comment as to whether or not the CIA was consulted by the State Department in the preparation of the INCSR and an explanation of the discrepancy between the CIA terminology of “minor” and the State Department’s terminology of “abundant” and “major”, an official stated that the agency stands by its data as published and, furthermore, has no record of any consultation by or information supplied to the State Department in relation to the INCSR.

In fact, the State Department seems to be completely at sea when it comes to the Caribbean in general. On its Caribbean Basin Security Initiative (CBSI) webpage, which refers specifically to the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), the map entitled “how the Caribbean Community benefits from the CBSI programs” includes the Dominican Republic, which is NOT part of CARICOM, yet omits Belize, Haiti and Suriname, which are.

In another questionable or deceptive claim, page 34 of the INCSR 2017 Volume II states:

“In 2016, US prosecutors alleged that government officials from Antigua and Barbuda participated in a corruption scandal involving the payout of close to $8 million in bribes by Brazilian construction contractor Odebrecht. The corruption allegations involve two high-level officials and two offshore banks in Antigua and Barbuda. Antigua and Barbuda continues to investigate allegations of money laundering.”

However, the Department of Justice (DOJ) federal court filing in relation to the same case states on page 24:

“73. Furthermore, in or about mid-2015, Odebrecht Employee 4 attended a meeting in Miami, Florida, with a consular official from Antigua and an intermediary to a high level government official in Antigua. In order to conceal ODEBRECHT’s corrupt activities, Odebrecht Employee 4 requested that the high-level official refrain from providing to international authorities various banking documents that would reveal illicit payments made by the Division of Structured Operations on behalf of ODEBRECHT, and agreed to pay $4 million to the high-level official to refrain from sending the documents. Odebrecht Employee 3 made three payments of 1 million Euros on behalf of ODEBRECHT in order to secure the deal. The contemplated fourth payment was never made.”

In other words, there is a more than double, unexplained $4.72 million discrepancy between the $8 million “payout” in bribes stated by the INCSR and the DOJ court filing in relation to Antigua and Barbuda, which states that $4 million was agreed to be paid and three million euros (US$3.28 million) actually paid.

The DOJ press office has not thus far responded to a request for an explanation as to why the State Department report, which is apparently based on information supplied by the DOJ, does not conform to what prosecutors had previously told the District Court.

During the course of our research into the disputed statements made in the INCSR, senior sources in other US government agencies have expressed grave concern that, if the State Department’s assertions of fact are shown to be baseless and/or unsupported by other government departments and agencies that should have been consulted but weren’t, the inescapable implication is that US foreign policy is flawed because it is being driven by false intelligence and reporting, and that the president himself may end up submitting an erroneous report to Congress based on such false reporting.

Furthermore, if it is shown that the adverse report in relation to Antigua and Barbuda and/or Nevis was based upon “alternative facts” rather than reality, how many other countries might be affected by such false reporting and how far back in the series of such reports in previous years does this extend?

IMAGES:

incsr-2017.jpg

cbsi_map.jpg

suspect_air_activity.jpg

For more on this story go to: http://www.caribbeannewsnow.com/topstory-Evidence-mounts-of-flawed-US-State-Department-Caribbean-report-34151.html