Greatest British horror film

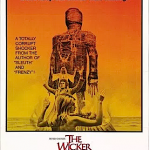

THE WICKER MAN: THE GREATEST BRITISH HORROR FILM

THE WICKER MAN: THE GREATEST BRITISH HORROR FILM

By Christopher Ratcliff

The Wicker Man comes from a long tradition of tricksy, blackly comic horrors that terrified and unsettled Britain in the early 70s.

There are some corkers in this period. Ken Russell’s gruelling The Devils, the hilarious Theatre of Blood starring Vincent Price, and Piers Haggard’s Blood on Satan’s Claw which joins Witchfinder General, The Devil Rides Out and The Wicker Man itself in a tiny little sub-genre of four called Folk Horror, a place where ancient pagan traditions make a cruel mockery of Christianity.

All the above films are excellent and you should certainly watch them all, however it’s The Wicker Man that stands out from the rest, like a tall, burning, giant-sized beacon of hopeless, crushing horror and leaving a long black scorch-mark of influence over four decades of British cinema and television.

THE WICKER MAN’S LEGACY

Obvious descendants of The Wicker Man include the work of The League of Gentleman, whose Royston Vasey is a Northern England stand-in for the remote Hebridean island of Summerisle (“you’ll never leave”). Ben Wheatley also channelled a similar pastoral horror in A Field in England and before that in the sublime Kill List, Wheatley took many of The Wicker Man’s themes and beats (ritual sacrifice, the heartbreakingly inevitable ending) and reconfigured them into a perfectly bitter, nihilistic modern retelling.

For me personally though, the influence of The Wicker Man and its perfectly distilled idea of folk horror is such that I’m now petrified of leaving the city.

All the best horror movies take a seemingly normal facet of everyday life (swimming in the sea, camping, taking a shower, watching television, owning a doll, Tim Curry) and makes it unbearable to look at in the same way ever again. The Wicker Man does this with great swathes of our green and pleasant land.

I come from a small town in Shropshire, which is certainly not the remotest place in the whole of the UK, and is very much a part of the thoroughly landlocked Midlands, but as I drive further into the countryside away from the A5 and into the rolling pastures and winding narrow roads of the bordering North Wales villages I can’t help but hum the opening song from The Wicker Man: ‘Corn Rigs’. I then feel the creeping sensation that I should turn around because I’d rather deal with random acts of pedestrian violence in Central London than the weird, occult rituals that I suspect my entire family has been indulging in for decades, which will finally be revealed to me now.

It’s an unfounded prejudice of the countryside, I admit, and It should be assuaged by the fact that as a 35 year-old non-Christian, non-virgin, I’ll probably be fine. Edward Woodward’s devout and unsullied Sergeant Howie wasn’t quite so lucky though.

SHOCKS ARE SO MUCH BETTER ABSORBED WITH THE KNEES BENT

The Wicker Man begins in a classic Church of England style congregation, full of tastefully dressed white middle-class English people watching Sergeant Howie earnestly receiving his holy communion. Although an anchor into normalcy in the 70s, watching this now, it all feels just as preposterously meaningless as anything to follow once Howie makes it to Summerisle.

The contrast of both religions and their bizarre rituals is entirely the point though and at least the nude, sexually liberated residents of Summerisle appear to be having more fun than the buttoned down stiffs back on the mainland.

SOME THINGS IN THEIR NATURAL STATE HAVE THE MOST VIVID COLORS

Howie later arrives on Summerisle to investigate the disappearance of a young girl named Rowan, after receiving a concerned letter from one of its residents. He is immediately confronted by the most intimidating of all social groups: locals. Deliberately obtuse, frustratingly unhelpful locals.

Instantly your heckles are raised by the smug self-satisfaction of these old-boys, but equally so by the pomposity of Howie, who doesn’t drop his tiresome imperiousness throughout the entire film. This is particularly acute during his first night’s stay at the local inn where he cuts through the joyful, bawdy singing of the punters with his ‘I am here on serious business’ spiel that is borne more as a way to halt the sexually provocative lyrics rather than a professional call for help.

This is Britt Ekland’s first appearance in the film, a gormless, jarringly dubbed landlord’s daughter/sexual plaything for the entire village named Willow, whose precocious sexuality will prove to be no match Howie’s zealous chasteness. In the ‘Final Cut’ version, which is the one I’m referencing here, scenes play out in a slightly different order with the timescale of events stretched out over a couple of nights instead of just one.

This basically means Britt Ekland’s nude slapping on the wall dance doesn’t happen until almost one hour in. Despite this being a particularly defining moment for men of a certain age, the power of the scene is made all the more intense for it being moved further into Howie’s journey, with his unexplored lust becoming all the more palpable.

It’s this contrast of the island’s progressive attitudes to human pleasures with Howie’s repression that pervades the entire film.

This is particularly prominent in the classroom scene where a group of younger teenage girls learn about the generative force of the penis instead of algebra or Wordsworth. When asked what the maypole dance taking place outside the window symbolises, the girls raise their hands in unison, calling out “the phallic symbol”. This is all to Sergeant Howie’s bafflement and disgust. “You can be quite sure I will be reporting this to the proper authorities” threatens Howie to their teacher Miss Rose.

This reluctance towards classroom sexual education was certainly a common attitude at the time, but seems hopelessly old-fashioned now. Howie is as displaced on Summerisle as much as he would be if he arrived in the 21st century.

YOU’LL SIMPLY NEVER UNDERSTAND THE TRUE NATURE OF SACRIFICE

It’s not just in the attitudes towards sex that you understand and sympathise with the Summerisle residents, but also in how its religion considers the afterlife. As Miss Rose says “we do not use the word dead”, the islanders believe that an expired life-force returns to the elements around them, the trees, the air, the earth. Their spiritual education focuses on reincarnation rather than resurrection. “Those rotting bodies are a stumbling block to the child’s imagination”.

In the post-God world of ours, we too find it far more appealing, realistic and indeed optimistic to believe that we are atoms that have occupied the universe for all of time and will be redistributed accordingly after death. This idea becomes much less of a metaphysical stretch than there being separate physical domains for angels and devils, where punishment and reward is meted out depending on how puritanical your Earthly existence has been. The Summerisle residents have far more in common with us in the present day who believe that life is full of pleasures that are there to be enjoyed here and now.

But then how does that tally with their belief that human sacrifice will appease the ancient gods and bring about a bountiful harvest? Despite their seemingly progressive thinking, the people of Summerisle reach even further back in time to find their religion, tiring of the ‘carrot and stick’ damnation the new God brought. As Lord Summerisle, the self-appointed ruler of the island states: God had his chance but he “blew it.”

With Lord Summerisle, Christopher Lee undoes years of typecasting and creates the most nuanced, quietly menacing and seductively charming role of his entire career. This was Lee’s very favourite performance of his and often proclaims, quite rightly, that The Wicker Man is the greatest British film ever made. However the major reason why the film works so phenomenally well is down to Edward Woodward’s utterly convincing portrayal of uptight virtuousness confronted by a bewildering and frustrating belief system.

In their brief scenes together, Summerisle is so patient, and understanding of Howie, cheerfully filling him in on the island’s history, despite the sergeant’s accusations of practicing fake religion and fake biology. “Your father brought you up to be a pagan!” Howie angrily snaps at Summerisle, to which he affably replies with playfulness “a heathen conceivably, but not an unenlightened one I hope.”

A MAN WHO HAS COME HERE AS A FOOL

Then we come to Howie’s desperate search for Rowan across the island, revealing creepy children in even creepier masks and a nude Ingrid Pitt in the most implausible bath ever manufactured. All of this is mere build-up to the inevitable.

A May Day parade, where the island-folk march to the beach while dressed as macabre, fanciful characters from the secret history of the British isles. All led by Lord Summerisle, adopting a pale face, a long black wig and sternly admonishing the disguised Howie who is failing to inhabit the role of Punch in a satisfying manner. “Cut some capers man!”

This revelry betrays the true intent of the parade, suckering in the audience as much as it does Howie. Such is the power of the film that on multiple rewatches you still cling to the hope that maybe this time Howie will make it out alive. Unfortunately the virgin Christian’s fate is sealed. Howie is the “right kind of adult”, one that the islanders took a great deal of research to find. A foolish man of the law who will come to the island of his own free-will.

Despite many false hopes, mainly provided by the uncovered ‘missing girl’ Rowan and a short-lived, electric-guitar soundtracked escape, Howie cannot escape his appointment with the wicker man.

And now for our more dreadful sacrifice…

For all their free-spirited progressiveness, there is ultimately something dreadful and medieval in the islanders’ beliefs. The slow reveal of the wicker man itself, the two-storey high construct built only for murder is truly the most frightening inanimate object ever committed to cinema.

“Killing me isn’t going to bring back your apples” is a too-late-in-the-day scientific argument from Howie, that finally reveals a level of realism so far absent from his religiously dictated logic. Then begins the slow, inescapable, sacrifice, that is no less painful to watch with repeated viewings.

Christopher Lee finally lets his inner maniacal villain loose as he raises his arms to the sun, while Edward Woodward screams impotently behind him, almost putting Lee off his stride. The fire rages, the island-folk sing and swing their arms in euphoric rapture and the wicker man and Howie turn to ash.

And that’s it. It’s all over. No hope for the God-fearing. No glory for the self-righteous Christians. However for the pagans the sun comes up on another day, bringing with it optimism and bounty.

It’s the duality of its absurdity and bleakness that makes The Wicker Man a satisfyingly complex vision. The contrasting performances of Lee and Woodward, the intertwining of organised religion with ancient custom and modern pragmatism, the evocation of idyllic folksiness interspersed with savagery and an ending that is essentially a blackly comic rug-pulling, all make The Wicker Man the greatest and most quintessential British film of all time.

IMAGES:

The Wicker Man

wicker man christopher lee sacrifice

christopher lee lord summerisle

christopher lee wicker man

wicker man maypole dance

wicker-man britt-ekland-naked

wicker-man naked ritual

For more on this story go to; http://methodsunsound.com/review-the-wicker-man-the-greatest-british-horror-film/