HALLOWEEN

HALLOWEEN IS TODAY (Oct 31)

The costumes are hung up ready. The jack-o-lanterns are lit. Everyone’s stocking up on candy. But, do you know the history of Halloween?

From Wikipedia

Halloween or Hallowe’en (less commonly known as Allhalloween,[5] All Hallows’ Eve,[6] or All Saints’ Eve)[7] is a celebration observed in many countries on 31 October, the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Saints’ Day. It begins the observance of Allhallowtide,[8] the time in the liturgical year dedicated to remembering the dead, including saints (hallows), martyrs, and all the faithful departed.[9][10][11][12] In popular culture, the day has become a celebration of horror, being associated with the macabre and supernatural.[13]

One theory holds that many Halloween traditions were influenced by Celtic harvest festivals, particularly the Gaelic festival Samhain, which are believed to have pagan roots.[14][15][16][17] Some go further and suggest that Samhain may have been Christianized as All Hallow’s Day, along with its eve, by the early Church.[18]Other academics believe Halloween began solely as a Christian holiday, being the vigil of All Hallow’s Day.[19][20][21][22] Celebrated in Ireland and Scotland for centuries, Irish and Scottish immigrants took many Halloween customs to North America in the 19th century,[23][24] and then through American influence various Halloween customs spread to other countries by the late 20th and early 21st century.[13][25]

Popular Halloween activities include trick-or-treating (or the related guising and souling), attending Halloween costume parties, carving pumpkins or turnips into jack-o’-lanterns, lighting bonfires, apple bobbing, divinationgames, playing pranks, visiting haunted attractions, telling scary stories, and watching horror or Halloween-themed films.[26] Some people practice the Christian observances of All Hallows’ Eve, including attending church services and lighting candles on the graves of the dead,[27][28][29] although it is a secular celebration for others.[30][31][32] Some Christians historically abstained from meat on All Hallows’ Eve, a tradition reflected in the eating of certain vegetarian foods on this vigil day, including apples, potato pancakes, and soul cakes.[33][34][35][36]

Christian origins and historic customs

Halloween is thought to have influences from Christian beliefs and practices.[44][45] The English word ‘Halloween’ comes from “All Hallows’ Eve”, being the evening before the Christian holy days of All Hallows’ Day (All Saints’ Day) on 1 November and All Souls’ Day on 2 November.[46] Since the time of the early Church,[47] major feasts in Christianity (such as Christmas, Easter and Pentecost) had vigilsthat began the night before, as did the feast of All Hallows’.[48][44] These three days are collectively called Allhallowtide and are a time when Western Christians honour all saints and pray for recently departed souls who have yet to reach Heaven. Commemorations of all saints and martyrs were held by several churches on various dates, mostly in springtime.[49] In 4th-century Roman Edessa it was held on 13 May, and on 13 May 609, Pope Boniface IV re-dedicated the Pantheon in Rome to “St Mary and all martyrs”.[50] This was the date of Lemuria, an ancient Roman festival of the dead.[51]

In the 8th century, Pope Gregory III (731–741) founded an oratory in St Peter’s for the relics “of the holy apostles and of all saints, martyrs and confessors”.[44][52] Some sources say it was dedicated on 1 November,[53] while others say it was on Palm Sunday in April 732.[54][55] By 800, there is evidence that churches in Ireland[56] and Northumbria were holding a feast commemorating all saints on 1 November.[57] Alcuin of Northumbria, a member of Charlemagne‘s court, may then have introduced this 1 November date in the Frankish Empire.[58] In 835, it became the official date in the Frankish Empire.[57] Some suggest this was due to Celtic influence, while others suggest it was a Germanic idea,[57] although it is claimed that both Germanic and Celtic-speaking peoples commemorated the dead at the beginning of winter.[59] They may have seen it as the most fitting time to do so, as it is a time of ‘dying’ in nature.[57][59] It is also suggested the change was made on the “practical grounds that Rome in summer could not accommodate the great number of pilgrims who flocked to it”, and perhaps because of public health concerns over Roman Fever, which claimed a number of lives during Rome’s sultry summers.[60][44]

By the end of the 12th century, the celebration had become known as the holy days of obligation in Western Christianity and involved such traditions as ringing church bells for souls in purgatory. It was also “customary for criers dressed in black to parade the streets, ringing a bell of mournful sound and calling on all good Christians to remember the poor souls”.[62] The Allhallowtide custom of baking and sharing soul cakes for all christened souls,[63] has been suggested as the origin of trick-or-treating.[64] The custom dates back at least as far as the 15th century[65] and was found in parts of England, Wales, Flanders, Bavaria and Austria.[66]Groups of poor people, often children, would go door-to-door during Allhallowtide, collecting soul cakes, in exchange for praying for the dead, especially the souls of the givers’ friends and relatives. This was called “souling”.[65][67][68] Soul cakes were also offered for the souls themselves to eat,[66] or the ‘soulers’ would act as their representatives.[69] As with the Lenten tradition of hot cross buns, soul cakes were often marked with a cross, indicating they were baked as alms.[70] Shakespeare mentions souling in his comedy The Two Gentlemen of Verona (1593).[71] While souling, Christians would carry “lanterns made of hollowed-out turnips”, which could have originally represented souls of the dead;[72][73] jack-o’-lanterns were used to ward off evil spirits.[74][75] On All Saints’ and All Souls’ Day during the 19th century, candles were lit in homes in Ireland,[76] Flanders, Bavaria, and in Tyrol, where they were called “soul lights”,[77] that served “to guide the souls back to visit their earthly homes”.[78] In many of these places, candles were also lit at graves on All Souls’ Day.[77] In Brittany, libations of milk were poured on the graves of kinfolk,[66] or food would be left overnight on the dinner table for the returning souls;[77] a custom also found in Tyrol and parts of Italy.[79][77]

Christian minister Prince Sorie Conteh linked the wearing of costumes to the belief in vengeful ghosts: “It was traditionally believed that the souls of the departed wandered the earth until All Saints’ Day, and All Hallows’ Eve provided one last chance for the dead to gain vengeance on their enemies before moving to the next world. In order to avoid being recognized by any soul that might be seeking such vengeance, people would don masks or costumes”.[80] In the Middle Ages, churches in Europe that were too poor to display relics of martyred saints at Allhallowtide let parishioners dress up as saints instead.[81][82] Some Christians observe this custom at Halloween today.[83] Lesley Bannatyne believes this could have been a Christianization of an earlier pagan custom.[84] Many Christians in mainland Europe, especially in France, believed “that once a year, on Hallowe’en, the dead of the churchyards rose for one wild, hideous carnival” known as the danse macabre, which was often depicted in church decoration.[85] Christopher Allmand and Rosamond McKitterick write in The New Cambridge Medieval History that the danse macabre urged Christians “not to forget the end of all earthly things”.[86] The danse macabre was sometimes enacted in European village pageants and court masques, with people “dressing up as corpses from various strata of society”, and this may be the origin of Halloween costume parties.[87][88][89][72]

In Britain, these customs came under attack during the Reformation, as Protestants berated purgatory as a “popish” doctrine incompatible with the Calvinist doctrine of predestination. State-sanctioned ceremonies associated with the intercession of saints and prayer for souls in purgatory were abolished during the Elizabethan reform, though All Hallow’s Day remained in the English liturgical calendar to “commemorate saints as godly human beings”.[90] For some Nonconformist Protestants, the theology of All Hallows’ Eve was redefined; “souls cannot be journeying from Purgatory on their way to Heaven, as Catholics frequently believe and assert. Instead, the so-called ghosts are thought to be in actuality evil spirits”.[91] Other Protestants believed in an intermediate state known as Hades (Bosom of Abraham).[92] In some localities, Catholics and Protestants continued souling, candlelit processions, or ringing church bells for the dead;[46][93] the Anglican church eventually suppressed this bell-ringing.[94] Mark Donnelly, a professor of medieval archaeology, and historian Daniel Diehl write that “barns and homes were blessed to protect people and livestock from the effect of witches, who were believed to accompany the malignant spirits as they traveled the earth”.[95] After 1605, Hallowtide was eclipsed in England by Guy Fawkes Night (5 November), which appropriated some of its customs.[96] In England, the ending of official ceremonies related to the intercession of saints led to the development of new, unofficial Hallowtide customs. In 18th–19th century rural Lancashire, Catholic families gathered on hills on the night of All Hallows’ Eve. One held a bunch of burning straw on a pitchfork while the rest knelt around him, praying for the souls of relatives and friends until the flames went out. This was known as teen’lay.[97] There was a similar custom in Hertfordshire, and the lighting of ‘tindle’ fires in Derbyshire.[98] Some suggested these ‘tindles’ were originally lit to “guide the poor souls back to earth”.[99] In Scotland and Ireland, old Allhallowtide customs that were at odds with Reformed teaching were not suppressed as they “were important to the life cycle and rites of passage of local communities” and curbing them would have been difficult.[23]

In parts of Italy until the 15th century, families left a meal out for the ghosts of relatives, before leaving for church services.[79] In 19th-century Italy, churches staged “theatrical re-enactments of scenes from the lives of the saints” on All Hallow’s Day, with “participants represented by realistic wax figures”.[79] In 1823, the graveyard of Holy Spirit Hospital in Rome presented a scene in which bodies of those who recently died were arrayed around a wax statue of an angel who pointed upward towards heaven.[79] In the same country, “parish priests went house-to-house, asking for small gifts of food which they shared among themselves throughout that night”.[79] In Spain, they continue to bake special pastries called “bones of the holy” (Spanish: Huesos de Santo) and set them on graves.[100] At cemeteries in Spain and France, as well as in Latin America, priests lead Christian processions and services during Allhallowtide, after which people keep an all night vigil.[101] In 19th-century San Sebastián, there was a procession to the city cemetery at Allhallowtide, an event that drew beggars who “appeal[ed] to the tender recollectons of one’s deceased relations and friends” for sympathy.[102]

Gaelic folk influence

Today’s Halloween customs are thought to have been influenced by folk customs and beliefs from the Celtic-speaking countries, some of which are believed to have pagan roots.[103] Jack Santino, a folklorist, writes that “there was throughout Ireland an uneasy truce existing between customs and beliefs associated with Christianity and those associated with religions that were Irish before Christianity arrived”.[104] The origins of Halloween customs are typically linked to the Gaelic festival Samhain.[105]

Samhain is one of the quarter days in the medieval Gaelic calendar and has been celebrated on 31 October – 1 November[106] in Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man.[107][108] A kindred festival has been held by the Brittonic Celts, called Calan Gaeaf in Wales, Kalan Gwav in Cornwall and Kalan Goañv in Brittany; a name meaning “first day of winter”. For the Celts, the day ended and began at sunset; thus the festival begins the evening before 1 November by modern reckoning.[109] Samhain is mentioned in some of the earliest Irish literature. The names have been used by historians to refer to Celtic Halloween customs up until the 19th century,[110] and are still the Gaelic and Welsh names for Halloween.

Samhain marked the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter or the ‘darker half’ of the year.[112][113] It was seen as a liminal time, when the boundary between this world and the Otherworld thinned. This meant the Aos Sí, the ‘spirits’ or ‘fairies‘, could more easily come into this world and were particularly active.[114][115] Most scholars see them as “degraded versions of ancient gods […] whose power remained active in the people’s minds even after they had been officially replaced by later religious beliefs”.[116] They were both respected and feared, with individuals often invoking the protection of God when approaching their dwellings.[117][118] At Samhain, the Aos Sí were appeased to ensure the people and livestock survived the winter. Offerings of food and drink, or portions of the crops, were left outside for them.[119][120][121] The souls of the dead were also said to revisit their homes seeking hospitality.[122] Places were set at the dinner table and by the fire to welcome them.[123] The belief that the souls of the dead return home on one night of the year and must be appeased seems to have ancient origins and is found in many cultures.[66] In 19th century Ireland, “candles would be lit and prayers formally offered for the souls of the dead. After this the eating, drinking, and games would begin”.[124]

Throughout Ireland and Britain, especially in the Celtic-speaking regions, the household festivities included divination rituals and games intended to foretell one’s future, especially regarding death and marriage.[125] Apples and nuts were often used, and customs included apple bobbing, nut roasting, scrying or mirror-gazing, pouring molten lead or egg whites into water, dream interpretation, and others.[126] Special bonfires were lit and there were rituals involving them. Their flames, smoke, and ashes were deemed to have protective and cleansing powers.[112] In some places, torches lit from the bonfire were carried sunwise around homes and fields to protect them.[110] It is suggested the fires were a kind of imitative or sympathetic magic – they mimicked the Sun and held back the decay and darkness of winter.[123][127][128] They were also used for divination and to ward off evil spirits.[74] In Scotland, these bonfires and divination games were banned by the church elders in some parishes.[129] In Wales, bonfires were also lit to “prevent the souls of the dead from falling to earth”.[130] Later, these bonfires “kept away the devil“.[131]

From at least the 16th century,[133] the festival included mumming and guising in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man and Wales.[134] This involved people going house-to-house in costume (or in disguise), usually reciting verses or songs in exchange for food. It may have originally been a tradition whereby people impersonated the Aos Sí, or the souls of the dead, and received offerings on their behalf, similar to ‘souling‘. Impersonating these beings, or wearing a disguise, was also believed to protect oneself from them.[135] In parts of southern Ireland, the guisers included a hobby horse. A man dressed as a Láir Bhán (white mare) led youths house-to-house reciting verses – some of which had pagan overtones – in exchange for food. If the household donated food it could expect good fortune from the ‘Muck Olla’; not doing so would bring misfortune.[136] In Scotland, youths went house-to-house with masked, painted or blackened faces, often threatening to do mischief if they were not welcomed.[134] F. Marian McNeill suggests the ancient festival included people in costume representing the spirits, and that faces were marked or blackened with ashes from the sacred bonfire.[133] In parts of Wales, men went about dressed as fearsome beings called gwrachod.[134] In the late 19th and early 20th century, young people in Glamorgan and Orkney cross-dressed.[134]

Elsewhere in Europe, mumming was part of other festivals, but in the Celtic-speaking regions, it was “particularly appropriate to a night upon which supernatural beings were said to be abroad and could be imitated or warded off by human wanderers”.[134] From at least the 18th century, “imitating malignant spirits” led to playing pranks in Ireland and the Scottish Highlands. Wearing costumes and playing pranks at Halloween did not spread to England until the 20th century.[134] Pranksters used hollowed-out turnips or mangel wurzels as lanterns, often carved with grotesque faces.[134] By those who made them, the lanterns were variously said to represent the spirits,[134] or used to ward off evil spirits.[137][138] They were common in parts of Ireland and the Scottish Highlands in the 19th century,[134] as well as in Somerset (see Punkie Night). In the 20th century they spread to other parts of Britain and became generally known as jack-o’-lanterns.[134]

Spread to North America

Lesley Bannatyne and Cindy Ott write that Anglican colonists in the southern United States and Catholic colonists in Maryland “recognized All Hallow’s Eve in their church calendars”,[139][140] although the Puritans of New England strongly opposed the holiday, along with other traditional celebrations of the established Church, including Christmas.[141]Almanacs of the late 18th and early 19th century give no indication that Halloween was widely celebrated in North America.[23]

It was not until after mass Irish and Scottish immigration in the 19th century that Halloween became a major holiday in America.[23] Most American Halloween traditions were inherited from the Irish and Scots,[24][142] though “In Cajun areas, a nocturnal Mass was said in cemeteries on Halloween night. Candles that had been blessed were placed on graves, and families sometimes spent the entire night at the graveside”.[143] Originally confined to these immigrant communities, it was gradually assimilated into mainstream society and was celebrated coast to coast by people of all social, racial, and religious backgrounds by the early 20th century.[144] Then, through American influence, these Halloween traditions spread to many other countries by the late 20th and early 21st century, including to mainland Europe and some parts of the Far East.[25][13][145]

Trick-or-treating and guising

Trick-or-treating is a customary celebration for children on Halloween. Children go in costume from house to house, asking for treats such as candy or sometimes money, with the question, “Trick or treat?” The word “trick” implies a “threat” to perform mischief on the homeowners or their property if no treat is given.[64] The practice is said to have roots in the medieval practice of mumming, which is closely related to souling.[163] John Pymm wrote that “many of the feast days associated with the presentation of mumming plays were celebrated by the Christian Church.”[164] These feast daysincluded All Hallows’ Eve, Christmas, Twelfth Night and Shrove Tuesday.[165][166] Mumming practiced in Germany, Scandinavia and other parts of Europe,[167] involved masked persons in fancy dress who “paraded the streets and entered houses to dance or play dice in silence”.[168]

In England, from the medieval period,[169] up until the 1930s,[170] people practiced the Christian custom of souling on Halloween, which involved groups of soulers, both Protestant and Catholic,[93] going from parish to parish, begging the rich for soul cakes, in exchange for praying for the souls of the givers and their friends.[67] In the Philippines, the practice of souling is called Pangangaluluwa and is practiced on All Hallow’s Eve among children in rural areas.[26] People drape themselves in white cloths to represent souls and then visit houses, where they sing in return for prayers and sweets.[26]

In Scotland and Ireland, guising – children disguised in costume going from door to door for food or coins – is a traditional Halloween custom.[171] It is recorded in Scotland at Halloween in 1895 where masqueraders in disguise carrying lanterns made out of scooped out turnips, visit homes to be rewarded with cakes, fruit, and money.[151][172] In Ireland, the most popular phrase for kids to shout (until the 2000s) was “Help the Halloween Party“.[171] The practice of guising at Halloween in North America was first recorded in 1911, where a newspaper in Kingston, Ontario, Canada, reported children going “guising” around the neighborhood.[173]

American historian and author Ruth Edna Kelley of Massachusetts wrote the first book-length history of Halloween in the US; The Book of Hallowe’en (1919), and references souling in the chapter “Hallowe’en in America”.[174] In her book, Kelley touches on customs that arrived from across the Atlantic; “Americans have fostered them, and are making this an occasion something like what it must have been in its best days overseas. All Halloween customs in the United States are borrowed directly or adapted from those of other countries”.[175]

While the first reference to “guising” in North America occurs in 1911, another reference to ritual begging on Halloween appears, place unknown, in 1915, with a third reference in Chicago in 1920.[176] The earliest known use in print of the term “trick or treat” appears in 1927, in the Blackie Herald, of Alberta, Canada.[177]

he thousands of Halloween postcards produced between the turn of the 20th century and the 1920s commonly show children but not trick-or-treating.[178] Trick-or-treating does not seem to have become a widespread practice in North America until the 1930s, with the first US appearances of the term in 1934,[179] and the first use in a national publication occurring in 1939.[180]

A popular variant of trick-or-treating, known as trunk-or-treating (or Halloween tailgating), occurs when “children are offered treats from the trunks of cars parked in a church parking lot”, or sometimes, a school parking lot.[100][181] In a trunk-or-treat event, the trunk (boot) of each automobile is decorated with a certain theme,[182] such as those of children’s literature, movies, scripture, and job roles.[183] Trunk-or-treating has grown in popularity due to its perception as being more safe than going door to door, a point that resonates well with parents, as well as the fact that it “solves the rural conundrum in which homes [are] built a half-mile apart”.[184][185]

Games and other activities

There are several games traditionally associated with Halloween. Some of these games originated as divinationrituals or ways of foretelling one’s future, especially regarding death, marriage and children. During the Middle Ages, these rituals were done by a “rare few” in rural communities as they were considered to be “deadly serious” practices.[198] In recent centuries, these divination games have been “a common feature of the household festivities” in Ireland and Britain.[125] They often involve apples and hazelnuts. In Celtic mythology, apples were strongly associated with the Otherworld and immortality, while hazelnuts were associated with divine wisdom.[199] Some also suggest that they derive from Roman practices in celebration of Pomona.[64]

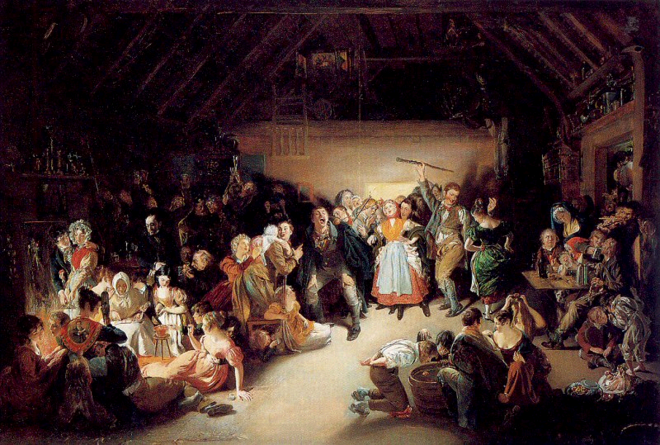

The following activities were a common feature of Halloween in Ireland and Britain during the 17th–20th centuries. Some have become more widespread and continue to be popular today. One common game is apple bobbing or dunking (which may be called “dooking” in Scotland)[200] in which apples float in a tub or a large basin of water and the participants must use only their teeth to remove an apple from the basin. A variant of dunking involves kneeling on a chair, holding a fork between the teeth and trying to drive the fork into an apple. Another common game involves hanging up treacle or syrup-coated scones by strings; these must be eaten without using hands while they remain attached to the string, an activity that inevitably leads to a sticky face. Another once-popular game involves hanging a small wooden rod from the ceiling at head height, with a lit candle on one end and an apple hanging from the other. The rod is spun round and everyone takes turns to try to catch the apple with their teeth.[201]

Several of the traditional activities from Ireland and Britain involve foretelling one’s future partner or spouse. An apple would be peeled in one long strip, then the peel tossed over the shoulder. The peel is believed to land in the shape of the first letter of the future spouse’s name.[202][203] Two hazelnuts would be roasted near a fire; one named for the person roasting them and the other for the person they desire. If the nuts jump away from the heat, it is a bad sign, but if the nuts roast quietly it foretells a good match.[204][205] A salty oatmeal bannockwould be baked; the person would eat it in three bites and then go to bed in silence without anything to drink. This is said to result in a dream in which their future spouse offers them a drink to quench their thirst.[206] Unmarried women were told that if they sat in a darkened room and gazed into a mirror on Halloween night, the face of their future husband would appear in the mirror.[207] The custom was widespread enough to be commemorated on greeting cards[208] from the late 19th century and early 20th century.

Another popular Irish game was known as púicíní (“blindfolds“); a person would be blindfolded and then would choose between several saucers. The item in the saucer would provide a hint as to their future: a ring would mean that they would marry soon; clay, that they would die soon, perhaps within the year; water, that they would emigrate; rosary beads, that they would take Holy Orders (become a nun, priest, monk, etc.); a coin, that they would become rich; a bean, that they would be poor.[209][210][211][212] The game features prominently in the James Joyce short story “Clay” (1914).[213][214][215]

In Ireland and Scotland, items would be hidden in food – usually a cake, barmbrack, cranachan, champ or colcannon – and portions of it served out at random. A person’s future would be foretold by the item they happened to find; for example, a ring meant marriage and a coin meant wealth.[216]

Up until the 19th century, the Halloween bonfires were also used for divination in parts of Scotland, Wales and Brittany. When the fire died down, a ring of stones would be laid in the ashes, one for each person. In the morning, if any stone was mislaid it was said that the person it represented would not live out the year.[110]

Telling ghost stories, listening to Halloween-themed songs and watching horror films are common fixtures of Halloween parties. Episodes of television series and Halloween-themed specials (with the specials usually aimed at children) are commonly aired on or before Halloween, while new horror films are often released before Halloween to take advantage of the holiday.

Christian observances

On Hallowe’en (All Hallows’ Eve), in Poland, believers were once taught to pray out loud as they walk through the forests in order that the souls of the dead might find comfort; in Spain, Christian priests in tiny villages toll their church bells in order to remind their congregants to remember the dead on All Hallows’ Eve.[240] In Ireland, and among immigrants in Canada, a custom includes the Christian practice of abstinence, keeping All Hallows’ Eve as a meat-free day and serving pancakes or colcannon instead.[241] In Mexico children make an altar to invite the return of the spirits of dead children (angelitos).[242]

The Christian Church traditionally observed Hallowe’en through a vigil. Worshippers prepared themselves for feasting on the following All Saints’ Day with prayers and fasting.[243] This church service is known as the Vigil of All Hallows or the Vigil of All Saints;[244][245] an initiative known as Night of Light seeks to further spread the Vigil of All Hallows throughout Christendom.[246][247] After the service, “suitable festivities and entertainments” often follow, as well as a visit to the graveyard or cemetery, where flowers and candles are often placed in preparation for All Hallows’ Day.[248][249] In Finland, because so many people visit the cemeteries on All Hallows’ Eve to light votive candles there, they “are known as valomeri, or seas of light”.[250]

Today, Christian attitudes towards Halloween are diverse. In the Anglican Church, some dioceses have chosen to emphasize the Christian traditions associated with All Hallow’s Eve.[251][252] Some of these practices include praying, fasting and attending worship services.[1][2][3]

O LORD our God, increase, we pray thee, and multiply upon us the gifts of thy grace: that we, who do prevent the glorious festival of all thy Saints, may of thee be enabled joyfully to follow them in all virtuous and godly living. Through Jesus Christ, Our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee, in the unity of the Holy Ghost, ever one God, world without end. Amen. —Collect of the Vigil of All Saints, The Anglican Breviary[253

Other Protestant Christians also celebrate All Hallows’ Eve as Reformation Day, a day to remember the Protestant Reformation, alongside All Hallow’s Eve or independently from it.[254] This is because Martin Luther is said to have nailed his Ninety-five Theses to All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg on All Hallows’ Eve.[255] Often, “Harvest Festivals” or “Reformation Festivals” are held on All Hallows’ Eve, in which children dress up as Bible characters or Reformers.[256] In addition to distributing candy to children who are trick-or-treating on Hallowe’en, many Christians also provide gospel tracts to them. One organization, the American Tract Society, stated that around 3 million gospel tracts are ordered from them alone for Hallowe’en celebrations.[257] Others order Halloween-themed Scripture Candy to pass out to children on this day.[258][259]

Some Christians feel concerned about the modern celebration of Halloween because they feel it trivializes – or celebrates – paganism, the occult, or other practices and cultural phenomena deemed incompatible with their beliefs.[260] Father Gabriele Amorth, an exorcist in Rome, has said, “if English and American children like to dress up as witches and devils on one night of the year that is not a problem. If it is just a game, there is no harm in that.”[261] In more recent years, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Boston has organized a “Saint Fest” on Halloween.[262] Similarly, many contemporary Protestant churches view Halloween as a fun event for children, holding events in their churches where children and their parents can dress up, play games, and get candy for free. To these Christians, Halloween holds no threat to the spiritual lives of children: being taught about death and mortality, and the ways of the Celtic ancestors actually being a valuable life lesson and a part of many of their parishioners’ heritage.[263] Christian minister Sam Portaro wrote that Halloween is about using “humor and ridicule to confront the power of death”.[264]

In the Roman Catholic Church, Halloween’s Christian connection is acknowledged, and Halloween celebrations are common in many Catholic parochial schools, such as in the United States,[265][266] while schools throughout Ireland also close for the Halloween break.[267][268] Many fundamentalist and evangelical churches use “Hell houses” and comic-style tracts in order to make use of Halloween’s popularity as an opportunity for evangelism.[269] Others consider Halloween to be completely incompatible with the Christian faith due to its putative origins in the Festival of the Dead celebration.[270] Indeed, even though Eastern Orthodox Christians observe All Hallows’ Day on the First Sunday after Pentecost, the Eastern Orthodox Church recommends the observance of Vespersor a Paraklesis on the Western observance of All Hallows’ Eve, out of the pastoral need to provide an alternative to popular celebrations.[2

Cost

Acccording to the National Retail Federation, Americans are expected to spend $12.2 billion on Halloween in 2023, up from $10.6 billion in 2022. Of this amount, $3.9 billion is projected to be spent on home decorations, up from $2.7 billion in 2019. The popularity of Halloween decorations has been growing in recent years, with retailers offering a wider range of increasingly elaborate and oversized decorations.[293]

END

For much more and references go to WIKIPEDIA

All IMAGES: Wikipedia