Killings in Mexico climbed to new highs in 2016, and the violent rhythm may only intensify

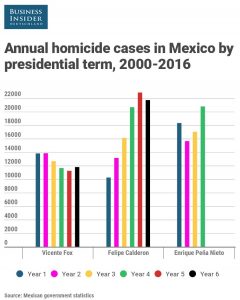

Mexico recorded the deadliest year of President Enrique Peña Nieto’s four-year-old sexenio, or six-year term, in 2016.

The country saw a 22% increase in homicide cases, rising from 17,034 in 2015 to 20,789 in 2016.

Individual homicide cases can contain more than one victim, and data released by the government showed that the number of homicide victims jumped 22.8%, from 18,673 in 2015 to 22,932 last year.

Government data released by the interior ministry each year since 1997 indicates that Peña Nieto’s first four years have had 71,808 homicide cases opened, putting his term on pace to exceed those of his two predecessors.

Vicente Fox saw 74,389 homicide cases opened during his term from 2001 to 2006, while Felipe Calderon, who deployed troops around Mexico in the move that is credited with kicking off Mexico’s cartel wars, recorded 104,794 homicide cases during his term from 2007 to 2012.

Recent reports by a Mexican nonprofit agency suggest that Mexican state governments, possibly at the direction of the federal government, have been manipulating the number of high- and low-level crimes they report. Such legerdemain may mean that the true number of violent deaths in Mexico is much higher.

Whatever the true number of homicides, government statistics indicate that they haven’t accumulated at a consistent rate over the last decade.

As noted by University of San Diego professor David Shirk, Calderon’s term was marked by a significant increase around 2008 and 2009 (2007 had the lowest number of homicides in Mexican history, Shirk said), but the killing slacked off during the first two years of Peña Nieto’s term.

“Peña Nieto came into office promising that within the first six months, we would see significant declines in violence,” Shirk said during a recent presentation at the Wilson Center in Washington, DC.

“That was extremely ambitious, but we did see a significant year-over-year decrease over the course of 2013 and 2014. And then, starting in 2015 and 2016, the numbers started to creep back up,” he added.

While the Mexican government’s reported homicide rate was 17 per 100,000 people in 2016, recent data indicates that the country is middle of the pack in Latin America, where countries like Venezuela, El Salvador, and Honduras well exceed it in deadly violence.

That 17 homicides per 100,000 people rate is Mexico’s fourth-highest recorded in the last 20 years, behind 1997’s rate and the peak years of 2010-2012.

The declines seen during Peña Nieto’s first two years as president have been reversed by increases in his third and fourth years in office.

Both 2015 and 2016 were marked by spikes in homicides during the latter half of the year.

In terms of individual homicide victims, data for which the Mexican government did not start releasing until 2014, 2016 also registered the highest monthly totals.

The 2,098 homicides recorded in July 2016 were the most recorded up until that point and were topped by each of the two following months.

The numbers of victims declined in each of the last three months of 2016, but never dropped below 2,000 a month.

While the overall homicides numbers have risen during Peña Nieto’s term in office, the increases have not been spread evenly around the country.

Deadly violence was “highly concentrated in certain parts of the country, particularly in the northwest during the worst of the violence,” in the latter half of Calderon’s term, Shirk said.

Killings were also concentrated in areas along “the Gulf coast, and, to some extent, the eastern border region,” he added.

With the recent spikes, Mexico’s violence again appears to be concentrating in specific areas — that is, zones that are strategically valuable to the criminal organizations largely driving the killing.

“In 2016, the violence again was highly concentrated, and the top 5 cities with the most violence accounted for 15% of all homicides over the course of the last year,” Shirk said.

Among those cities were Tijuana, where the Sinaloa cartel is clashing with rivals over control of one of the most lucrative drug-trafficking routes in the world; Acapulco, a Pacific coast port city centrally located along smuggling routes and near an extensive opium-cultivating region; and Ciudad Juarez, which is also a valuable trafficking corridor where the Sinaloa cartel is competing for control.

However, while that concentration “sounds like a lot,” Shirk said, “during the peak of the violence in 2011, the top 5 cities accounted for about a third of all homicides in Mexico. So if you saw a big drop in Ciudad Juarez, it had a national-level effect.”

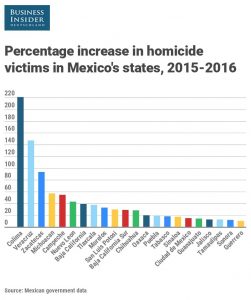

Overall, 22 of Mexico’s 32 states saw increases in the number of homicide victims between 2015 and 2016.

Some of those states, like Guerrero (where Acapulco is located), Sinaloa, and Mexico City, usually have elevated homicide numbers — the latter because its population is so much larger than that of other states.

That said, many of those states saw increases, some of them double-digit percentages. Spikes were more pronounced elsewhere, particularly in states valuable to drug traffickers.

Chihuahua, home to Ciudad Juarez, saw a 27.7% increase in homicides. Baja California, where Tijuana is located, had a 38.7% increase. In Veracruz, a Gulf coast state strategically located for traffickers, saw a 147.5% jump, and Colima, where the Sinaloa cartel is fighting for supremacy, killings jumped 221%.

To the extent that organized crime is responsible for the increase in killing, two trends appear to be in play: the ongoing fragmentation of criminal groups, particularly in the southwest, and the likely more significant emergence of the powerful Jalisco New Generation cartel.

“The one thing that I think you could identify as causing much of the increase in violence in the last year or two is the reaccommodation and repositioning of the New Generation cartel,” Shirk told Business Insider in an interview earlier this month.

“That to me is the one piece of the puzzle that we can look to and say, ‘Wow, New Generation is clearly expanding, asserting itself in lots of ways,’ [like] kidnapping [‘El Chapo’ Guzmán’s] children,” he added. “It’s doing stuff that clearly constitutes an aggressive expansion of influence and presumably capability and control.”

Feeding the violence are a number of socioeconomic and political factors. Many in Mexico remain mired in poverty with few job opportunities outside of criminal enterprise. Impunity also remains widespread, with only about 1% of crimes in Mexico being punished.

Shirk noted to Business Insider that the recent increase in deadly violence hadn’t manifested itself with the suddenness seen during the Calderon administration. But, for several reasons, this increase may not soon relent.

Amid the slow growth of an economy weakened by a prolonged slump in oil prices, the Mexican federal government has decreased its spending on security since 2015, according to analysis of government outlays by Reuters.

“If the government doesn’t have any money for security measures … it’s going to be terrible. (The number of murders) is probably going to get to the worst level it’s ever been,” Leo Silva, who led the Drug Enforcement Administration office in the northern Mexican city of Monterrey until 2015, told Reuters in January.

“If those programs are cut out, you’ve got all these at-risk youth, and they’re just going to rot in the street,” Silva said. Such spending cuts may also hamsting efforts to expand and strengthen the criminal-justice apparatus and to rein in impunity.

If increases in homicides continue apace, “2017 could be a year of records,” Mexican security analyst Alejandro Hope wrote at the end of January.

“To keep the rhythm of growth of 2016, the annual total of homicides will be higher than 30,00o” in 2017, Hope said, citing statistics gathered by the Mexican national statistics agency, which are typically higher than those released by the Mexican interior ministry.

“If the rhythm of expansion reduces to half of that experienced last year,” Hope added, homicides “would exceed the absolute total of 2011, the most violent year in the recent history of Mexico.”

IMAGES:

Enrique Pena Nieto Mexico Mexico’s President Enrique Pena Nieto gestures during the signing of an agreement relating to trade and transportation of natural gas at the National Palace in Mexico City, March 13, 2015. Edgard Garrido/Reuters

Mexico annual homicide cases by sexenio 2000 2016 Mexico has seen a sustained increase in homicides since the late 2000s. Mexican government data/Christopher Woody

Homicide cases in Mexico 2013 2016 The third and fourth years of Enrique Peña Nieto’s term have seen spikes in homicides. Mexican government data/Christopher Woody

Percentage increase in homicides in Mexico 2015 2016 In 2016, 22 of Mexico’s 32 states saw increases in homicide victims compared to 2015. Mexican government data/Christopher Woody

Mexico Cancun soldiers mall shooting Soldiers walk inside Plaza Las Americas mall following reports of gunfire in Cancun, Mexico, January 17, 2017. Gunmen attacked the state prosecutor’s office in the Caribbean resort city. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Guerrero homicide death violence killing Mexico Acapulco

Forensic officers cover the body of Alejandro Gallardo Perez, 23, after he was shot dead near his home in San Agustin, on the outskirts of Acapulco, Guerrero state, Mexico, April 15, 2016. AP Photo/Enric Marti

For more on this story go to: http://www.businessinsider.com/mexico-homicides-in-2016-under-enrique-pena-nieto-2017-2