Mandolins make a comeback, but there’s still reason to fret

By Adam Bernstein From Chicago Tribune

“Watch the sale of the banjo, mandolin and guitar; when it falls off, there is something wrong with the musical progress of the nation. These are instruments of the people.”

John Philip Sousa, 1907

They have endured swing, rock, disco, rap, hip-hop and swing again.

But you’ve probably never heard of them.

Since the brass-mad Jazz Age, the once-prominent classical mandolin orchestras have died off. Only a handful of bands survived, many of which still pluck away on the same Sousa marches and Joplin rags composed at the turn of the century.

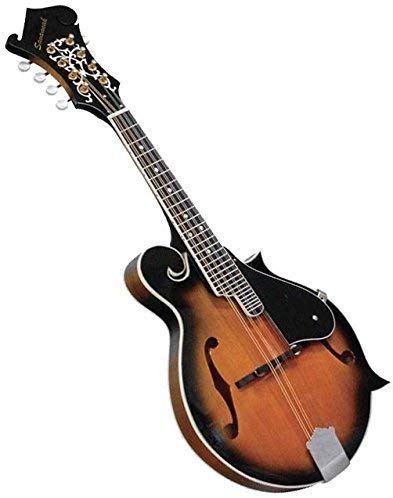

The majority of mandolinists still strumming on their eight-stringed, violin-size contraptions — which are capable of a gentle, harplike tremolo — have been at it for many years. They perform infrequently, charge nothing and often play to small crowds.

By contrast, the mandolin is still mainstream in Europe, particularly Germany, where there are at least 1,000 mandolin bands. There, the instrument is taught in grade school and not dismissed as being easy to learn by ear.

Although far from its status in Germany, the mandolin in America has been rediscovered by adults and, more important, teenagers, who for the last decade have tried to inject more visibility and professionalism into their playing of the instrument.

Many mandolin players move to the classical style after years playing the instrument in bluegrass or folk bands.

“I’ve stretched my abilities,” said Carvel H. Bass, 51, a former folk fiddler and now the first-mandolinist in the Los Angeles Mandolin Orchestra. “It’s a real workout, and it leads me into a whole body of music I’d never otherwise encounter.”

But its sound, sharper than a guitar’s yet described as “almost heavenly” and “shimmering” by its devotees, is also being picked up by classically trained musicians. They understand that the mandolin is tuned like a violin and has variations similar to a chamber group’s, such as the viola (mandola) and cello (mandocello).

The Louisville Mandolin Orchestra is one of the more vigorous examples of the vibrant change among the current bands. The group is only a decade old, and is the only such ensemble in a city that had eight in 1910. The 24-piece band is led by founder Mike Schroeder, 41. A bluegrass musician, Schroeder discovered the classical style through a visiting German performer and, echoing the sentiments of many other players interviewed, loved the camaraderie of a full orchestra.

The Louisville Mandolin Orchestra has hired composers to write new pieces and has found several innovative ways to approach the music. Last summer, the group recorded with several brass bands a series of newspaper marches, a genre popular in the late 19th Century, celebrating the glory of a hometown paper.

As president of the Classical Mandolin Society of America, Schroeder’s goal for the 12-year-old group is to see it offer scholarships to students and consider moving its annual convention to the summer instead of November to make it easier for younger people to attend.

The 1999 gathering will be held in Minneapolis, where Schroeder hopes to have quartets play at local schools. That’s exactly what he’s done throughout Kentucky.

The Louisville band has several high school members, including Leah Neuhauser, 17, who picked up the instrument after 12 years as a violinist. “I went to a mandolin concert to see a friend,” Neuhauser said. “It just sounded really neat, really different to me after I’d been in string orchestras.”

Jake Skocir, 85, of Milwaukee picked up the instrument at a friend’s house in 1932 and hasn’t put it down since. Since 1938, he has been a member of the oldest continually playing mandolin orchestra in the United States, the Milwaukee Mandolin Orchestra, which 15 years ago changed its name from the The Bonne Amie Musical Circle. Last year the group released its first CD, “Mandolins in the Moonlight.”

Skocir said he is “happy kids are keeping the tradition alive.”

“All the kids (today) know is rock,” he added. “(Mandolin) music is new to them. . . . They never heard the mandolin. Forty years ago, it was dying out. There were five groups in Milwaukee at that time, but a lot of them were oriented ethnically — Spaniards, Mexicans, Italians. (Many) kids weren’t exposed to it.”

Jack El-Hai, 40, the founder and manager of the Minnesota Mandolin Orchestra, said he also was moved by the instrument’s different sound. After meeting Schroeder at the mandolin society’s convention, El-Hai founded his own group in 1991. Most of his members are in their 30s and 40s and were bluegrass musicians.

“Everyone knows what the guitar is and what it sounds like. The mandolin needs constant explanation and interpretation,” said El-Hai, who plays a 1917 Gibson mandocello, a larger-size mandolin. “People always ask, `What’s in that case? A ukulele, a banjo?’ No one ever guesses mandolin. . . . Many express non-conformity in the way they dress, but I guess I express it in what I play.”

Less than a century ago, there would not have been the same opportunity for non-conformity, because so many people played the mandolin. The instrument did not enter the public consciousness in America until 1880, when a group of Spanish conservatory students played a variation on the mandolin in New York, said Paul Ruppa, the music director of the Milwaukee Mandolin Orchestra who also wrote his master’s degree about the history of the mandolin.

“Within a month, a group of Italians started in the United States a mandolin ensemble and started calling themselves The Spanish Students,” said Ruppa, 48.

The mandolin “fit the laid-back and quiet and elegant” lifestyle of the public then, said mandolin historian Maxwell McCullough of McLean, Va., the vice president of the Classical Mandolin Society of America. “People were looking in those days (for something) that was genteel.”

The instrument became a rage, with an outpouring of light classics and rags put on the market by music publishing houses.

McCullough said the instrument was refined in the early 1900s by the Gibson Co., whose designs departed from the “plinky, plinky European style.” The Gibson folks made the mandolin look like a violin with a carved top and back. “It made projection better and was more mellow” in sound, said McCullough, 62, a former manager for IBM who now plays with the Washington, D.C.-area Takoma Mandoleers band.

The instrument had several notable interpreters, including Kiev-born Dave Appollon, who played in vaudeville and nightclubs from the 1920s until his death in 1972.

Playing what was to be called bluegrass music, Bill Monroe and His Blue Grass Boys also kept the instrument in sight starting in the 1930s, long after the mandolin orchestras died in the wake of the flaming youth fad of the Jazz Age.

Other musicians have come along sporadically, using mandolin in jazz, so-called world music and even rock.

But the orchestras themselves are considered dinosaurs.

Members “either die or move to Florida,” said Francine von Bernewitz, a life-long mandolinist in her 70s whose husband started the Takoma Mandoleers in 1923. “We lost eight people last year because of age.”

Chicago has no mandolin orchestra, a scenario that is “very typical” of most communities, said Norman Levine, 68, who publishes Mandolin Quarterly magazine from his home in Kensington, Md., and founded the Classical Mandolin Society of America in 1986.

“One of the problems is half the (population who wanted to learn) couldn’t find a mandolin teacher,” Levine said. “In the Chicago area, since Jethro Burns died, people have been asking me where (they) can find another mandolin teacher.”

Kenneth “Jethro” Burns (1920-1989), who lived in Evanston and was a member of the country comedy team Homer and Jethro, played and taught all styles of music but was considered a pioneer of jazz mandolin.

Despite a prevalence of Chicago mandolin bands just 20 years earlier, by the early 1980s, the city had only one group, led by aging conductor Albert Van de Velde, said jazz mandolinist Don Stiernberg, 42, of Skokie.

Andrew Kyriazes, 72, who started what became the Van de Velde ensemble, has confined his playing to family affairs for the last 35 years.

Kyriazes, now of Palatine, said he’d “love to know how many people are involved still” with the mandolin. “I’m looking at the (Fretted Instrument Guild of America) directory, and it’s from 1961, and for all I know, half these people might be dead.”

———-

Information about The Classical Mandolin Society of America, other mandolin-related groups and mandolin concerts nationwide can be found at the Mandolin Cafe Web site (www.mandolincafe.com).

For more on this story go to: https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1999-01-22-9901220131-story.html