‘The SOS in my Halloween decorations’

Inside a notorious Chinese labour camp, a dissident smuggled an SOS letter into the Halloween decorations he was forced to manufacture. Years later, a woman in the US opened a box of fake tombstones and found his note. It seemed impossible at that moment that they would ever meet.

A few years ago, as the evenings began getting colder and darker, Julie Keith remembered the graveyard kit in her loft.

She’d picked it up for $29.99 from the supermarket chain, Kmart, a couple of years before that. It contained polystyrene headstones, fake skulls and bones, black spiders and a cloth drenched in imitation blood.

It had been gathering dust in the loft ever since. But when her daughter told her she wanted a Halloween-themed fifth birthday party, Julie, then 42, thought of the kit and went upstairs to fetch it.

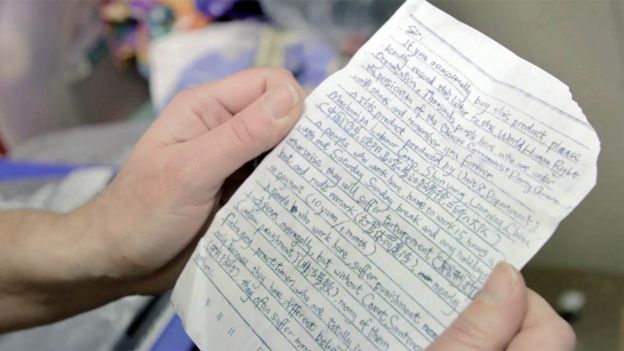

Then, as she opened the box in her living room, a sheet of lined paper fell out.

Image copyrightFLYING CLOUD PRODUCTIONS

Image copyrightFLYING CLOUD PRODUCTIONSOn it was a message, neatly hand-written in blue ink. Julie’s daughter picked it up and asked her to read it. The English was broken and frequently mis-spelt, but its meaning was clear enough.

“Sir,” it began. “If you occassionally buy this product, please kindly send this letter to the World Human Right Organization. Thousands people here who are under the persicution of the Chinese Communist Party Government will thank and remember you forever.”

Julie read on. The note said that the graveyard kit had been produced in unit eight, department two of Masanjia labour camp in Shenyang, China. Inmates there had to work there for 15 hours a day seven days a week: “Otherwise, they will suffer torturement, beat and rude remark. Nearly no payment (10 yuan/1 month).” Today 10 yuan is roughly equivalent to £1.10 or US$1.44.

Prisoners were detained on average for one to three years without a formal court sentence, the note continued. Some of them belonged to the spiritual movement Falun Gong. “They often suffer more punishment than others,” the note said.

Image copyrightFLYING CLOUD PRODUCTIONS

Image copyrightFLYING CLOUD PRODUCTIONSThere was no signature at the end.

“I was kind of in shock,” Julie says. “I just couldn’t believe that something like that was here, in front of me.”

It seemed miraculous that this scrap of paper had travelled thousands of miles to her home in Damascus, near Portland, in the US state of Oregon, and then languished in her home for two years until 2012. She tried to imagine how desperate its author must have felt, how much courage it must have taken to slip it in among the decorations.

Julie, a manager at the Goodwill thrift store chain, knew nothing at all about this person, but it was obvious to her that he or she desperately wanted the world to know what was happening at Masanjia.

Find out more

Julie Keith and Leon Lee were speaking to Outlook on the BBC World Service

You can listen again here

Julie didn’t know where to begin, so she logged on to Facebook and asked for advice.

She took a photo of the note and posted it for her friends to see. They suggested that she contact human rights organisations, so Julie rang up and left messages with several – but she never received a reply.

Still, Julie didn’t give up. She took the letter into work and showed it to her company’s PR manager, who contacted a journalist on The Oregonian, a local newspaper. The paper sent an intern to interview Julie – but for a couple of months, once again, there was silence.

Then suddenly, just before Christmas 2012, the story finally ran. It was on The Oregonian’s front page, and immediately Julie’s phone started ringing.

Image copyrightFLYING CLOUD PRODUCTIONS

Image copyrightFLYING CLOUD PRODUCTIONSTV networks and newspapers from around the world were asking her to speak – she found herself at the centre of a major international story.

Julie was delighted at first. She’d helped to spread the word about conditions in Masanjia, just as the note’s author had asked. But then she read the comments below the online news reports.

Many strongly criticised her. By releasing the note in full – with its reference to the exact unit and department of the labour camp in which the author was held – she’d made a serious error, these commenters said. Surely now the whistleblower would be identified by the authorities and singled out for extra punishment?

“It crushed me,” Julie says.

“I felt like, at that point, I maybe had done the wrong thing. I felt terrible but I just kept referring back to the letter – this is what the writer wanted. He wanted me to publicise this.”

The self-doubt kept nagging at Julie, however. But then, in mid-2013, she was contacted by the New York Times. The author of the note slipped in among the Halloween tombstones and skulls had been tracked down. And he had a message for her.

Image copyrightFLYING CLOUD PRODUCTIONS

Image copyrightFLYING CLOUD PRODUCTIONSFive years earlier, Sun Yi looked out of a window into the darkness as he ate his meagre dinner at Masanjia prison camp, and saw a group of people moving through the gloom outside. He couldn’t see well, but they appeared to be carrying human skulls and thigh bones.

Sun Yi was horrified. He’d only recently been sentenced but already he’d heard rumours that some of his fellow inmates were tortured to death. This appeared to be confirmation.

Another inmate told him the group he’d seen were known as the Eighth Team, and they worked on what was called the “ghost job”.

Not long afterwards, in June 2008, a guard called out Sun Yi’s name. He was taken to a building and sent to a room on the fourth floor. He realised he’d been assigned to the Eighth Team – the very last thing he had wanted to happen.

When he entered the room, Sun Yi saw what looked like a tombstone in front of him. He picked it up and realised it was made of white polystyrene. It would soon be covered in black dye, and it would be Sun Yi’s job to make it look old by rubbing it with a wet sponge until the white underneath began to show through.

Image copyrightEL TORO STUDIOS

Image copyrightEL TORO STUDIOSSun Yi had no idea what Halloween was, though it came as a great relief that no actual dead bodies were involved – it was baffling to him that anyone would want these morbid decorations.

“He was wondering why people would buy this kind of scary stuff,” says Canadian film-maker Leon Lee, who would later get to know Sun Yi. “Until one day a guard told him Western people have this kind of a culture, a so-called festival, and that’s why they are making it.”

Soon black dye covered Sun Yi’s face and body. He worked from 04:00 until 23:00 or midnight, breaking only to eat. At night, he later recalled, his hands would move as he slept, as if he was polishing tombstones in his dreams.

Before his arrest, Sun Yi had been an engineer for an oil and gas company. His troubles began after a chance meeting with a group of people exercising outdoors near his home in Beijing – they were practising Falun Gong, a spiritual movement loosely based on Taoism and Buddhism, and Sun Yi soon joined up.

Falun Gong was initially tolerated by China’s communist authorities after its emergence in the early 1990s, but after a few years they began to see the movement as potential threat, because of its growing size. Criticisms began to appear in the state media, prompting some 10,000 practitioners to take part in a silent protest outside the ruling Communist Party’s Beijing headquarters in 1999. The movement was banned soon after that.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESThe Chinese government then launched a relentless publicity campaign against Falun Gong, branding it an “evil cult”. Its followers soon had to practise in secret, risking prosecution and arrest.

In February 2008, during a crackdown in the run-up to the Beijing Olympics, Sun Yi was caught. Arrested during a raid at an underground press, he was sentenced to two-and-a-half years in prison.

That is when he was taken to Masanjia, a “re-education through labour” camp in the north-east of the country that housed criminals as well as dissidents and political prisoners.

While he was there, his wife wrote to him telling him she wanted a divorce. She and other relatives had been harassed and detained following his arrest, and she knew that members of her family would fail background checks – and therefore be unable to get jobs – as long as she was married to him.

Sun Yi held on to the letter. It was the only thing in Masanjia that was his.

Around this time, an idea occurred to him. He knew the graveyard kits he was making were for export because the labels were in English. Why not write letters and hide them inside the boxes? Maybe someone would find one and tell the world what was happening in Masanjia?

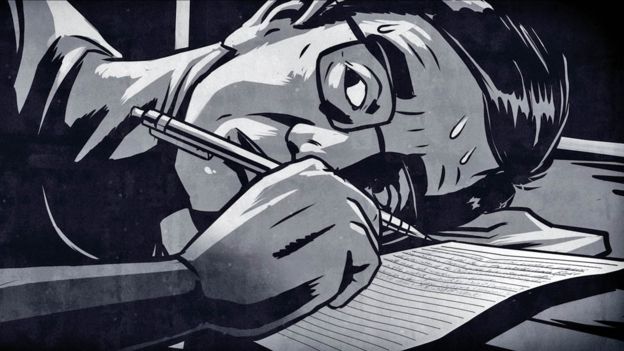

One night, as he lay in his cell surrounded by 30 or 40 sleeping fellow inmates, Sun Yi turned on his side so that he faced the wall. All he could hear were the crickets chirping outside. Quietly, he opened a sheet of paper and pulled out a pen. He knew that guards were on patrol.

He picked up his pen and began to write.

Image copyrightEL TORO STUDIOS

Image copyrightEL TORO STUDIOSSun Yi later estimated he had written about 20 letters in total during his time at Masanjia. He had to be careful about slipping them into the tombstone kits because he never knew which ones would be inspected. He usually did it during breaks, when other prisoners were outside.

But once, as he put a letter into a box, another inmate saw what he was doing. Sun Yi had to take a risk and tell him what he was up to.

“Good,” said the other prisoner. “Do you have any more that I could help you hide?”

Sun Yi began sharing his letters with other Falun Gong devotees inside the camp, and one night one of the notes was discovered by guards during a search. The guards tortured the prisoner on whom the letter was found – they knew he must have an accomplice, because he didn’t speak English. But he didn’t reveal Sun Yi’s involvement.

Although Sun Yi escaped further punishment on that occasion, he didn’t manage to evade the next crackdown against Falun Gong prisoners. Like many others, he was forced to stand with his wrists handcuffed to a bunk bed in an effort to make him recant. If he fell asleep, his legs would give way and the handcuffs would cut into him like knives.

Sun Yi was released from Masanjia in September 2010. He carried on practising Falun Gong and printing samizdat literature, but he kept a low profile. And then in 2012, while browsing Western news sites on the internet – he’d found a way to bypass China’s censorship of the web – he came across a story about a letter that had been found among a box of Halloween decorations in Oregon. His letter.

Image copyrightFLYING CLOUD PRODUCTIONS

Image copyrightFLYING CLOUD PRODUCTIONSFour months after the story about Julie’s Halloween decorations went viral, a Chinese magazine called Lens published an expose about conditions inside Masanjia. The online version of the story was later deleted, but the Chinese authorities appear to have been shaken by the publicity. Shortly afterwards the government announced that it was ending the “education through labour” system and freeing some 160,000 prisoners.

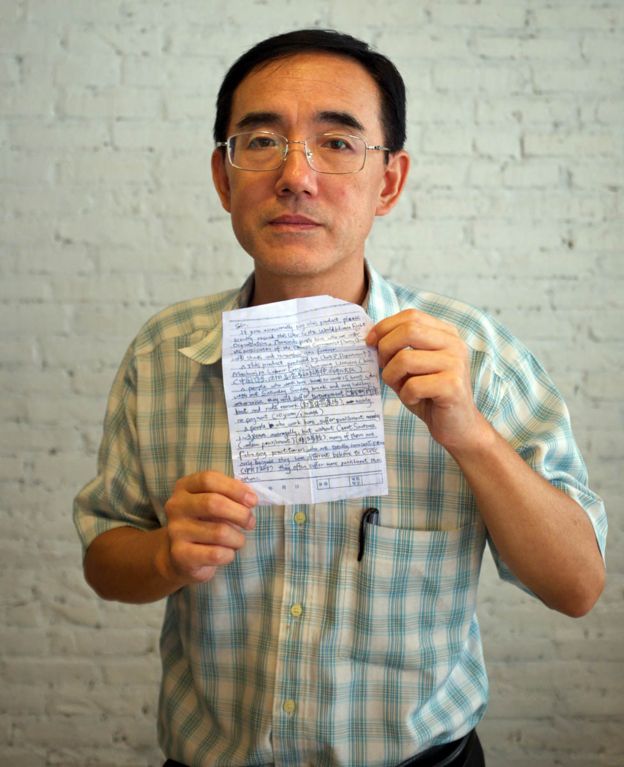

It was not long after this that Julie heard Sun Yi – indirectly at first. “The New York Times contacted me and told me that they had been in contact with him and thatthey were doing a story,” she says. He’d written another letter – this time, it was just for her. In it, he wrote “that he was very glad that I publicised the letter – that’s exactly what he wanted”, Julie remembers.

“I was so thrilled – to know that he was alive, for one, and that he was proud of me and just knowing that I did the right thing.”

Sun Yi had not only been contacted by the New York Times, but also by Leon Lee, a Canadian director with a record of covering human rights abuses in China. Sun Yi agreed to be the subject of a film and began sending Lee footage of himself.

He understood this was an enormous risk.

Image copyrightMARCUS FUNG

Image copyrightMARCUS FUNGHe and his ex-wife were planning to remarry and leave China together, but then a fresh crackdown on Falun Gong practitioners began. Police raided Sun Yi’s ex-wife’s home and told her to contact them if she saw Sun Yi. Before long, Sun Yi was arrested.

While he was in custody, though, his health began to deteriorate, so he was released on health grounds – and he took the opportunity to flee to Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia, with help from Leon Lee.

Life was tough there. Sun Yi applied for refugee status, but as an asylum seeker he was unable to work. He couldn’t contact his wife for fear of getting her into trouble with the Chinese authorities. Living off his savings, he spent his days learning Indonesian and English.

It was at this point that Julie flew out to meet Sun Yi. Lee, who’d put them in touch, would be there to film the encounter. Julie had worried about him constantly during the four years that had passed since she’d found his letter. She had heard some of Sun Yi’s story from Lee, and was troubled by the thought that she had contributed to his difficulties.

When she arrived at his modest apartment in Jakarta, she didn’t know what to expect.

“It was like we had this instant connection,” says Julie.

“He called me his sister. It was like we’d known each other forever.”

Image copyrightMARCUS FUNG

Image copyrightMARCUS FUNGThey exchanged gifts. He bought her flowers, while she bought him a book about life in Oregon. She also brought him the note he had written in Masanjia, and the polystyrene tombstone. “He seemed really thankful to bring all this back full circle,” Julie says.

He asked her about the festival of Halloween. What happened to the pumpkins after they were carved, Sun Yi wondered. Did you eat them? Julie explained this wasn’t the custom. He also wanted to know what “RIP” stood for. Rest in Peace, Julie told him. She explained that it was a message of goodwill for the dead.

After she’d flown home, Sun Yi wept when he recalled Julie’s visit. He had never imagined she would travel all that way to see him. “I really appreciate that she did that,” he tells Leon Lee, in an interview on camera. “I don’t know how to thank her. She feels like family.”

But if life in Jakarta was hard, it soon got worse. Shortly after Julie’s visit, Sun Yi was contacted by a suspected Chinese agent – and two months later he died of acute kidney failure. Despite a request from his ex-wife and sisters, there was no investigation into the cause of death. Leon is suspicious: “He had no kidney problems before and when I was there in Indonesia he seemed perfectly healthy.”

Julie was devastated when she heard the news. “I so badly wanted a happy ending for him,” she says.

She feels honoured to have known Sun Yi. “He was the most resilient, strong person I have ever met – for someone to go through what he did and come out and be able to talk about it and share his experiences with the world – it’s just incredible.”

Her chance connection with Sun Yi changed her life, she says. She became more globally aware – conscious of where the products in the dollar stores near her home had come from, and she resolved to pass on this understanding to her children.

For human rights campaigners, the relevance of Sun Yi’s story hasn’t diminished. When the re-education through labour system formally ended, Amnesty International said many camps were simply renamed prisons or rehabilitation centres, and that dissidents and Falun Gong followers continued to be held in them, often without trial. Torture remained “widespread” in cases considered politically sensitive, including those of Falun Gong practitioners, the organisation reported in 2015.

Recently, China has been accused of locking up hundreds of thousands of Muslims without trial in its western region of Xinjiang. The government denies the claims, buta BBC investigation found significant new evidence of internment camps.

Leon Lee’s film Letter from Masanjia received its UK premier at the Cambridge International Film Festival on 26 October.

TOP IMAGE: FLYING CLOUD PRODUCTIONS

For more on this story go to: https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-45976946