Trademarks v. artistic freedom

Trademarks versus artistic freedom of expression: milestone referral for preliminary ruling

Trademarks versus artistic freedom of expression: milestone referral for preliminary ruling

By Olivier Vrins, Jeroen Muyldermans Contributed by ALTIUS Intellectual Property Belgium

From ILO

In a high-profile trademark infringement case involving Moët Hennessey Champagne Services (MHCS) – owner of the famous Champagne brand Dom Pérignon – and a Belgian painter, the courts were asked to strike a balance between the right to property, including intellectual property, and artistic freedom of expression. Both intellectual property and artistic freedom are recognised as fundamental rights by a number of conventions, most notably the European Convention on Human Rights and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

Facts

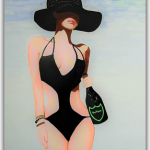

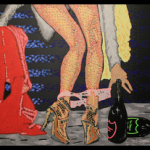

At the centre of the dispute was a Belgian artist whose paintings can be described as falling under the pop art or pointillism movements (Figures 1 and 2). While the work features a number of luxury brands, mostly French and Italian luxury consumer or design brands, the artist received particular interest from Dom Pérignon as its trademarks featured in a large number of paintings. Some of the paintings were unique or featured the bottle and trademarks only in a secondary role. The paintings were allegedly intended as an homage to the brand, representing images of a decadent and almost soft-erotic lifestyle in the artist’s view.

While MHCS accepted that the artist’s work enjoyed the privilege of artistic freedom, the same was not true for a series of other paintings, which were all quite similar and used the same image of a bottle and setting, differing only in the colours used. Further, the artist had launched a collection of sweaters and T-shirts with a stylised and simplified image of these paintings. These items were intended to function as a promotional tool for the paintings and as an homage as such. The artist called the paintings and clothing the Damn Pérignon Collection (Figures 3 and 4) and explained that he had chosen this name because Dom Pérignon was such a “damn” good brand.

MHCS initiated legal proceedings, seeking an injunction against the marketing and advertising of the clothing items and the series of paintings which featured the Dom Pérignon figurative trademarks and the sign Damn Pérignon as their main identifier. MHCS relied on unfair competition law, a number of Benelux and EU trademarks covering the shape of the Dom Pérignon bottle and the well-known label which had been used for decades to identify the iconic Dom Pérignon Champagne wines (Figures 5 to 7).

Decision

In a 12 April 2018 judgment, the Brussels Commercial Court ruled in favour of MCHS. It considered that the use of the figurative sign and the words Damn Pérignon on clothing constituted a type of trademark use that, for the average consumer, indicated the commercial origin of said goods. Such use to distinguish clothing was manifestly done to:

take unfair advantage of the reputation of the Dom Pérignon trademarks and was deemed likely to dilute those marks; and

tarnish Dom Pérignon’s reputation due to the offending meaning of ‘damn’ and the often boudoir nature of the promotional context of those paintings and clothing (Figure 8).

The court considered that the artist had no due cause for the infringing use, as that notion aims to balance the trademark owner’s interest in protecting the functions of its trademark against the infringing use. In reaching that conclusion, the court stressed that the clothing articles’ main purpose was to secure a commercial advantage and gain its own name recognition in the market and that it did not express an artistic opinion. The use was therefore likely to create the false impression that the clothing articles were either produced under licence of or endorsed by MHCS. As a consequence, MHCS’s right to defend the mark was given precedence over the alleged right of artistic freedom.

Regarding the collection of paintings, the court considered that the use of the Dom Pérignon marks was not a type of trademark use made to indicate the commercial origin of the paintings. Such use falls under Article 10(6) of the EU Trademark Directive (2015/2436/EC)(1) and is actionable if it is made “other than… for the purposes of distinguishing goods or services, where use of that sign without due cause takes unfair advantage of, or is detrimental to, the distinctive character or the repute of the trade mark”. Benelux has, until now, been the only EU member state to have transposed that provision. Questions or issues on the uniform interpretation of Benelux law, including those transposed from optional provision of the trademark directive, are brought before the Benelux Court of Justice. They fall outside EU harmonisation.(1)

In its judgment, the court noted that it was essential to weigh the two fundamental rights at issue. In doing so, it was first necessary to determine the criteria appropriate for striking that balance, before assessing the merits of the claim. The court thus referred the following questions to the Benelux Court of Justice:

Can the right to freedom of speech, and the artistic freedom of expression in particular, as guaranteed by Article 10 of the European Convention for the protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms and Article 11 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, constitute a ‘due cause’ within the meaning of Article 2.20.1.d) of the Benelux Convention on Intellectual Property?

In the affirmative, which are the criteria that a national court must take into account in striking the balance between those fundamental rights, and the importance to be attached to each of those criteria?

In particular, should the national court take account of the following, or any other, criteria:

the extent to which the expression has a commercial nature or purpose

the extent to which the expression covers a general interest, is socially relevant or enters into a debate

the relationship between those two criteria

the degree of reputation of the trademark relied on

the extent of the infringing use, its intensity and systematic nature as well as its coverage in terms of territory, time and volume, also having regard to the message which the expression aims to convey

the extent to which the expression, and circumstances accompanying that expression, such as its name, title or way of promoting, affect the distinctive character, reputation and image of the trademark relied on (the ‘advertising function’)

the extent to which the expression displays a proper creative contribution and the extent to which one attempted to prevent confusion or association with the trademark relied on, or the impression that there is a commercial or other link between the expression and the trademark owner (the ‘function of indicating origin’), also having regard to the way in which the trademark owner secured a certain image and reputation for trademark through advertising and communication strategies.

Comment

Trademarks have been used in the framework of societal debates and social criticisms. The more reputed a trademark, the more it must cope with such debates and criticisms. However, in this case, it remains to be seen whether the artist’s clear commercial intentions and the (probably) limited relevance of societal debate will be favoured over the trademark owner’s right of exclusivity. The decision is expected to set an important precedent on how to strike a fair balance between freedom of speech and the protection of trademarks when these two concepts conflict.

For further information on this topic please contact Olivier Vrins or Jeroen Muyldermans at ALTIUS by telephone (+32 2 426 1414) or email ([email protected] or [email protected]). The ALTIUS website can be accessed at www.altius.com.

Endnotes

(1) ECJ 21 November 2002, C-23/01, ECLI:EU:C:2002:706, Robeco/Robelco.

The materials contained on this website are for general information purposes only and are subject to the disclaimer.

ILO is a premium online legal update service for major companies and law firms worldwide. In-house corporate counsel and other users of legal services, as well as law firm partners, qualify for a free subscription.

Forward Share

Authors

IMAGES:

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8