US: What will Biden’s presidency mean for banking regulation?

By Douglas Thomson From GBRR

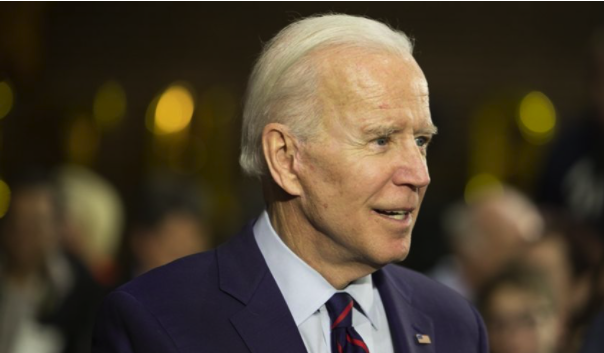

Joe Biden has defeated Donald Trump to become the United States’ next president – triggering an overhaul of the federal government and its regulatory agencies. What can banking regulation practitioners around the world expect from the new administration?

US media networks announced on 8 November that in the election five days earlier Biden had won enough states to become president. He is set to take over the presidency on 20 January 2021.

He is the first candidate in 28 years to defeat an incumbent president, and it will be the first time since 1976 a party has been ousted from the executive branch after only four years in power.

The victory gives Biden appointing power over the United States’ federal banking regulators, opening up new potential directions in areas including fintech, climate risk, bank M&A, capital adequacy and more. It will also mean a shift in priorities which, even when ostensibly aimed at the retail end of the banking market, will still impact wholesale banking operations.

Legislative prospects

Biden himself was active in financial regulation during his long career as a senator representing Delaware, a state which has branded itself as “the Luxembourg of the United States” for its history of bank-friendly state-level regulation. Delaware’s influence on Biden’s inner circle remains strong, with its former senator Ted Kaufman among his closest advisors and a co-chair of his transition team.

Since the 2008 financial crisis – which coincided with his departure from the Senate for the vice-presidency – Biden has walked back some of his earlier pro-banking politics. He says a 1999 vote, to repeal the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act’s separation between retail and investment banking, is the sole vote from his 36-year career in the senate he now regrets.

Ahead of the election, some talked of a new Glass-Steagall, or legislation bringing the financial sector under the ambit of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, or an expansion of the Community Reinvestment Act. But bar an upset in two runoff elections scheduled for January in Georgia, Republicans are expected to keep control of the US Senate – dimming the prospects for significant legislative change.

“Legislation of any type is extremely difficult these days in Washington, and the prospects for enactment of any kind of major bank legislation in the short term are very low, particularly if Republicans retain control of the Senate,” Covington & Burling partner Jeremy Newell tells GBRR.

That puts the onus on the regulators – and the individuals Biden appoints to staff and lead them – as the driver of his administration’s policy in this area. But those individuals too will need support from Republican senators to win confirmation to their posts.

White & Case partner Pratin Vallabhaneni says that, while it is not on Biden’s agenda, it’s likely his administration may nevertheless see reforming primary legislation for anti-money laundering and the Bank Secrecy Act.

“It is one area that will require primary legislation to be passed in terms of actually changing beneficial ownership requirements and suspicious activity report rules,” he says. “Legislation is likely to move forward on this topic regardless of who controls the Senate, considering the strides it made under the congressional composition.”

Personnel is policy

Biden will have the opportunity of naming a new chair for the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), after incumbent Jay Clayton announced on 16 November his attention to retire at the end of the year, ahead of the expiration of his term in mid-2021. Former CFTC chair Gary Gensler has been linked with the post, as have former SEC commissioners Rob Jackson and Kara Stein. He can also name two new members of the Federal Deposit Insurance Commission (FDIC), one of whom must be Republican.

The new president might also have the chance to put the OCC under new leadership, as current Comptroller of the Currency Brian Brooks is serving only in an acting capacity. But on 17 November Trump sought to cut that possibility off, nominating Brooks for a full five-year term. Should Brooks be confirmed by the US Senate that would leave him in place for the entirety of Biden’s presidential term and into the next.

But the Trump administration’s legacy within the regulators will continue for some time to come even without Brooks’ confirmation, with several Trump appointees including FDIC chair Jelena McWilliams, Federal Reserve board chair Jerome Powell, and CFTC chair Heath Tarbert all serving terms that stretch long into the new administration.

An open question is the fate of two seats on the Federal Reserve board, which have been open since the retirements of Janet Yellen and Sarah Bloom Raskin in January.

President Trump’s nominee to Raskin’s seat, Chris Waller, has been uncontroversial. But his nominee to Yellen’s, Judy Shelton, has faltered amid concerns over her unconventional stances including supporting a return to the gold standard and eliminating federal deposit insurance schemes, and her confirmation prospects remain uncertain. The Senate declined to progress Shelton’s nomination to a final vote on 18 November.

The appointments Biden has made so far in the financial regulatory space have leaned towards the ‘progressive’ end of the Democratic party. Last week Biden named his transition team charged with facilitating the transition, including a dedicated task force led by Gensler responsible for taking over the United States’ federal financial regulatory agencies.

During Barack Obama’s administration Gensler was responsible for bringing foreign banks under the ambit of the Volcker Rule and for a complete overhaul of swaps market regulation – surprising many for whom he had gained a conservative reputation during his earlier tenure overseeing derivatives regulation at the US Treasury Department during Bill Clinton’s administration a decade earlier.

Biden has tapped other progressive names to his team, including too-big-to-fail critic and former International Monetary Fund chief economist Simon Johnson and Dennis Kelleher, head of advocacy group Better Markets which has critiqued the turnover of personnel between regulators, private practice and in-house work.

In a piece last year for The American Prospect Kelleher accused the Trump administration of an “assault on financial reform” by lowering capital requirements, weakening stress tests, allowing more proprietary trading and reducing the prudential oversight of systemically significant banks.

Climate risk

Addressing climate change is expected to be one of the top priorities of the new administration, with Biden expected to join the Paris Climate Agreement immediately upon taking office and to establish an executive office for climate change in the White House which may have input into financial regulation.

“Based on initial signals from the Biden campaign and transition team, I would anticipate that regulators will consider disclosure, reporting, and how banks are integrating the financial risks from climate change into their governance frameworks, risk management processes, and business strategies,” Institute of International Banks general counsel Stephanie Webster says.

“Whichever path they decide to take, it is extraordinarily important that the regulators also prioritise international coordination and consistency,” Webster warns, noting that the home jurisdictions of many IIB members have already started addressing the financial risks associated with climate change in their regulatory and supervisory frameworks.

“I expect US regulators will recognise the importance of consistency around the globe, to promote both effective outcomes and efficiency in compliance,” she says.

On 30 October New York’s state Department of Financial Services – under the aegis of Linda Lacewell, an appointee of Democratic governor Andrew Cuomo – became the first significant financial regulatory agency in the US to instruct banks to incorporate climate risk into their governance frameworks. While such actions have been missing from federal agencies during the Trump administration, most practitioners expect this to change under Biden’s.

Some among the federal regulators have already begun inching towards climate-related policy, with the CFTC issuing a report on managing climate risk earlier this year.

Possibly in a recognition of the change of political climate, Fed chair Powell said shortly after the election that the Fed was “very actively in the early stages … of getting up to speed” on how climate risks might impact the sector, and since then the Fed’s semi-annual report on financial stability has encouraged banks to detail how their investments could be impacted by climate risks.

“Although the regulators’ appetite for introducing climate risk into the bank regulatory framework has been lukewarm in the past, that will now clearly change,”Newell says, pointing to Powell’s remarks as a signal for that change.

A more climate-oriented Fed might take account of climate as a factor in its regulation of systemic risk, and Newell says the regulator will take a “hard look” at stress tests for the largest banks’ climate-related risks.

Newell also suggests more active participation in the global-level Network for Greening the Financial System, which Fed announced on 10 November it will seek to join. International cooperation involving the Basel Committee could also allow for the Fed to lead other regulators in linking the risk-weighting of assets for capital purposes to determinations of whether they are climate change-accelerating.

Fintech regulation

The Trump era has coincided with a significant expansion of activity in the fintech space, and regulators around the world have shown increasing attention to the regulatory implications of innovations such as crypto-assets and digital currencies.

This has ramped up at the OCC especially since March, when it hired Brooksfrom San Francisco-based exchange Coinbase, initially as first deputy comptroller and then as acting comptroller upon the unexpected departure of comptroller Joseph Otting in May.

During his less than six months on the job Brooks has issued guidance allowing banks to hold custody of cryptocurrencies and funds for fiat-backed stablecoin issuers, issued a new national bank charter for payment companies including fintechs, and issued an advance notice of proposed rulemaking opening the scope for future rulemaking on a wide range of fintech-related issues.

Interest in the potential of fintech is by no means limited to Republicans, and Democrats have focused on its potential to expand financial inclusion. Fed governor Lael Brainard, who has been the focus of speculation as Biden’s potential pick for Treasury secretary, is overseeing the Federal Reserve’s research into a digital dollar, and Gensler has also spoken positively of blockchain’s potential as a “change catalyst”.

But it’s unclear whether regulators’ recent attention to the development of fintech-led payments technologies will be matched under the new administration, with several progressive Democrats recently complaining that the OCC under Brooks had shown an “excessive” focus on crypto-related financial services during the covid-19 pandemic, as well as critiquing its “unilateral actions in the digital activities space”.

Covington & Burling partner Michael Nonaka says to expect continued development of the regulatory framework for crypto-assets however. “The regulatory framework for cryptocurrency will evolve and become more nuanced as traditional financial institutions offer cryptocurrency products and services, and as emerging cryptocurrency companies continue to enter the regulatory perimeter that applies to traditional financial institutions,” he says.

“There is intense industry lobbying around this issue, so legislation clarifying the regulatory path for crypto-assets may finally gain traction,” Vallabhaneni says, adding that some in Biden’s circle had “deep ties” to the crypto-assets world.

“However, it is also likely that the heads of the banking and capital markets regulators may not be as crypto-friendly as those currently in place now, and the new administration may be sympathetic to state claims of regulatory autonomy, and be resistant to laws that pre-empt state laws,” he adds.

Should Biden have the opportunity to replace Brooks as Comptroller, it could also lead to a shift in the OCC’s stance in defending the so-called ‘fintech charter’, which allows non-depository fintech companies to apply for Special Purpose National Bank charters, from challenges filed against it in the federal courts by the New York Department for Financial Services.

The US District Court for the Southern District of New York found in DFS’s favour last year, and the OCC is currently appealing before the Second Circuit Court of Appeals.

Recent rulemaking

One of the most recent acts of regulatory rulemaking under the Trump administration has been the OCC and FDIC’s policy, finalised in June following an adverse ruling by the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, reaffirming banks’ ability to sell loans to third parties regardless of state-level usury laws so long as they were valid when made. Democrats initially opposed the so-called “valid-when-made” rule as enabling banks to avoid state interest rate limits.

Another recent rulemaking measure which may face re-examination is the “true lender” rule, finalised by the OCC last month, which is intended to resolve uncertainty in bank-nonbank lending partnerships about the identity of the lender. Democrats have opposed that too as undermining consumer protection, arguing that it allows nonbank lenders to skirt state usury laws through their partnerships with federally regulated banks.

It’s likely both rules will be revisited under the Biden administration, but Covington & Burling partner Karen Solomon, former chief counsel at the OCC, says wholesale reversal of either is unlikely. “The agencies’ valid-when-made rules are based on statutes that are usually interpreted consistently with one another,” she says. “Reversal of either agency’s rule could affect the other, and it’s unclear whether the agencies would come to the same conclusion about rescinding or withdrawing the rules.”

Rescinding the rules could also undercut the agencies’ positions in lawsuits, filed against them by multiple state attorneys-general seeking to set the rules aside, she says.

Specifically with respect to the true lender rule, Solomon adds that reversing it “does not address the underlying issue, which is that the federal usury statutes allow banks to use the usury rate of the state where they are ‘located’, and some states have substantially higher usury ceilings than others”.

Vallabhaneni tells GBRR the identity of the Comptroller – whether Brooks or a Biden nominee – will play a role in the extent of the changes, as will the makeup of the FDIC board.

“I would expect lawsuits challenging both rules to continue with the Biden administration allowing the process to unfold in the judiciary,” he predicts. “The administration will face continued lobbying efforts from the industry as the need for a harmonised federal standard in this area continues to grow.”

Bank size

Pittsburgh-based bank PNC announced on 16 November it would be buying the US arm of Spanish bank BBVA – a US$11.6 billion transaction which will make PNC the country’s fifth-biggest bank.

That transaction was linked to consolidation moves in BBVA’s home market, where the proceeds give the bank funds to pursue its own M&A deals after La Caixa and Bankia formed Spain’s largest bank earlier this year, but it also comes in the context of a Trump administration that has overseen accelerated consolidation – and in anticipation of an incoming administration expected to take a more sceptical view of banking scale.

During the campaign Biden’s economic policy development task force – made up of representatives of his own campaign and that of defeated primary rival Senator Bernie Sanders – called for bank mergers concluded during the Trump administration to be reviewed on antitrust, racial equity and workers’ rights grounds. It also suggested “expanding safeguards” dividing the operations of retail and investment banks, though this would likely require primary legislation.

A recent Davis Polk & Wardwell client memo suggests the administration “may attempt to appoint regulators who are committed to increased scrutiny of large acquisitions”, making it harder for large bank M&A transactions to win approval.

A smooth transition?

So far Biden has not had cooperation from the outgoing Trump administration, as the incumbent president is refusing to concede his loss in the election. But practitioners GBRR spoke to said they do not expect this to cause operational difficulties in the banking regulation space.

“Any change of administration presents its own, unique set of challenges for the incoming administration, and the longer the delay, the greater the possibility of operational difficulties,” Webster tells GBRR. But she and other practitioners GBRR spoke to said they do not expect this to cause operational difficulties in the banking regulation space.

Webster emphasises that most staff at regulatory agencies are non-political employees whose careers have spanned multiple transitions. “We have full confidence that they will continue to carry out the work of the agencies professionally and assist the incoming political appointees in overcoming any hurdles that the delayed transition may bring.”

She notes that the US Administrative Procedures Act ensures a “transparent, deliberative” rulemaking process which should promote a smooth transition in the agencies’ leadership.

Solomon agrees that disruptions for the federal banking regulators specifically are unlikely as their funding sources are independent of any individual administration.

“This means that the agencies’ day-to-day operations, including preparation for the new administration, should be able to proceed smoothly,” she says.

For more on this story go to: GBRR