Venezuela, PetroCaribe, and the “Orgy of Corruption”

By INGRID ARNESEN, JIM CLANCY, DALE ELLIOTT and KIMONE FRANCI From CIJN

How An Oil Alliance Founded by then-Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez to Confront U.S. Influence in the Caribbean Collapsed into Broken Deals, Dashed Hopes and Rampant Corruption.

Hugo Chavez, then the Venezuelan President, sat at a wooden table deep in the sweltering jungle, flanked by his ministers and a full television production crew.

“ALO PRESIDENTE!” Chavez roared into his microphone. A stampede of local villagers elbowed their way to the front of the platform.

“Tell me your problems!” So began his weekly, 10-hour long television show broadcast live from under a thick canopy of palm trees . It was 2002 and El Presidente had just quashed a coup.

“What do you need?” bellowed Chavez. A woman pleaded for an ambulance to get her son to the hospital. Chavez turned to his Health Minister ordering him to get one. Done!

A farmer needed a tractor. “Done!” shouted the Agricultural Minister.

Chavez’ legendary and spontaneous generosity was on full display. No fuss. No waiting. El Presidente is in charge. In his Bolivarian Revolution, everyone will get everything they want.

Chavez was the 21st Century socialist “somewhere between Simon Bolivar and Santa Claus,” says Professor Anthony Bryan of University of the West Indies. Hugo Chavez died in 2013.

Standing on one of the world’s largest petroleum reserves, Chavez had a lot of oil and money to hand out. But Chavez had other ideas about how he could use his seemingly endless petro-dollars. Through an energy finance project called PetroCaribe, he could supply his Caribbean neighbors with oil, then use his leverage to spread his revolutionary ideology and repel U.S. influence in the superpower’s backyard.

What is PetroCaribe

In 2005, Chavez launched PetroCaribe, seeing the potential of a regional alliance he could create and control with oil. PetroCaribe would strengthen his presence in the Caribbean and counter the longstanding U.S. role.

The PetroCaribe Agreement guaranteed a stable flow of oil on unprecedented financial terms. It shielded member states from the extreme peaks in global oil prices that at the time reached more than US$ 100 per barrel. It also yielded instant revenue.

“It wasn’t cheap oil, it was cheap credit,” says David Goldwyn, former U.S. State Department special envoy for international energy.

PetroCaribe supplied oil at market prices in exchange for a 40% down payment. The 60% balance would be repaid over 25 years at 1% interest. Governments sold the oil at market prices to local distributors, earning immediate profits from the deferred balance.

These new revenues were intended to enable cash-strapped governments to finance social and economic development.

“It was a bonanza!” says Kesner Pharrel, a leading Haitian economist.

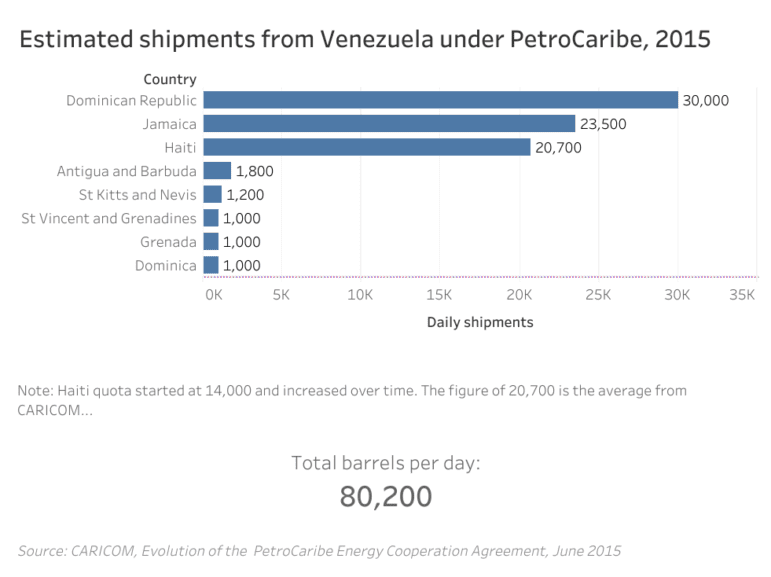

From day one, thousands of barrels of Venezuelan oil began moving through the Caribbean.

Almost 15 years later, what seemed like a promise to pull many Caribbean nations out of poverty has collapsed in parallel with Venezuela’s oil economy. Low income housing, healthcare, education and other social projects are now left without funding. Instead of transitioning to renewable sources of energy, they are overdependent on hydrocarbons. Once again, most are at the mercy of volatile oil prices.

No Caribbean country is more emblematic of corruption under the PetroCaribe Agreement than Haiti, the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere.

From 2008 to 2016, Haiti accumulated US$ 2 Billion in PetroCaribe profits. That money was intended to lift Haitians out of poverty, modernize their infrastructure, and stabilize the economy. None of these happened.

The Haitian government, during three successive administrations, had gone on a

spending spree, burning through US$ 1.7 billion of PetroCaribe funds and had little to show for it.

“It was an orgy of corruption!” declared Fritz Jean, the former Governor of Haiti’s Central Bank. “We missed an enormous opportunity. We could have used this financing, about US$ 2 billion, to double or triple the value through investments.”

The Demise of PetroCaribe

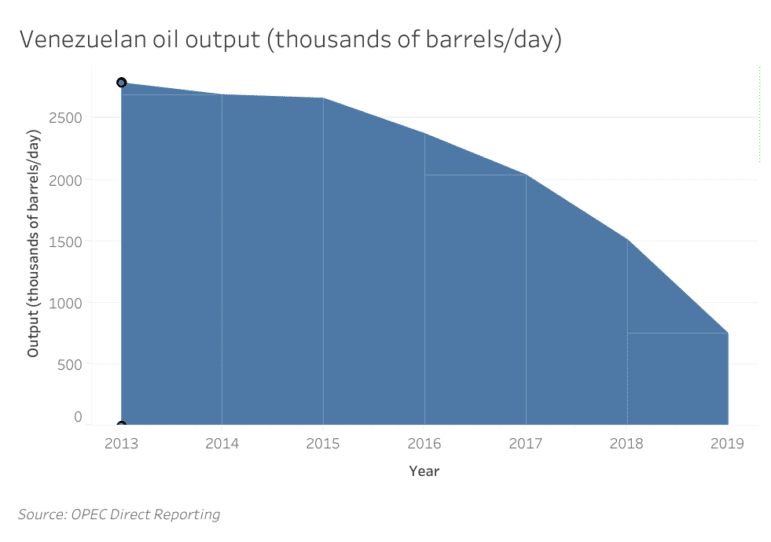

Venezuela’s political crisis worsened after the death of Hugo Chavez in 2013. Within a year, global oil prices began a steep decline. PDVSA, the state-owned oil giant struggled to maintain output. From a high of 3.2 Million barrels per day, production plunged to barely 700,000 in October 2019. By then, Venezuela was already well into an economic freefall.

Note: Oil industry analysts warn Venezuela’s oil production is higher than reported to OPEC. Tanker operators are turning off their transponders to avoid U.S. sanctions.

In 2017, the U.S. imposed drastic sanctions on Venezuela as Chavez’ handpicked successor, President Nicolas Maduro, clung to power. A year later, in June 2018, Venezuela announced it was ending oil shipments to PetroCaribe members. It had little choice.

In 2019, Washington ratcheted up sanctions, blocking all US Dollar-based transactions including outstanding debt payments owed by PetroCaribe members. The sanctions effectively put an embargo on Venezuelan oil sales that comprised more than 95% of its export earnings.

Venezuela’s external debt was more than US$ 100 Billion, much of it owed to China and Russia. Venezuela was using most of the oil it was producing to pay down that debt.

Despite the bleak outlook in Caracas, some PetroCaribe members hope the deal will come back.

Gaston Browne, Prime Minister of Antigua and Barbuda, told CIJN, “PetroCaribe is at a standstill. As you know, the situation in Venezuela is such that they cannot supply presently even the social programs that were funded under PetroCaribe, those are being threatened. And we’re hoping that the issue in Venezuela will be resolved very soon.”

Different Outcomes

How well Caribbean island nations fared under PetroCaribe entirely depended on how they managed the revenues generated. Some invested and spent wisely, using the funds as intended in social development programs and budget support that would keep their economies healthy.

Dr. Wesley Hughes, former CEO of the PetroCaribe Development Fund in Jamaica, praised the agreement. “During the global financial crisis, Venezuela emerged as the most important source of bilateral assistance to Jamaica. And had it not been for that assistance, through the PetroCaribe arrangement, the Jamaican economy would have been in dire circumstances. Things would have been far worse than they turned out to have been.”

Country Reports

But Caribbean analysts don’t all agree. “I am one of the critics that would say it (PetroCaribe) slowed alternative fuels, created debts, spurred corruption,” says Anthony Bryan. “We began to see pretty early that Chavez was posturing while others thought he was the greatest thing since sliced bread.”

Hugo Chavez had proudly pointed out that the long-term loans gained under PetroCaribe came “with no strings attached.” What also wasn’t there was any oversight of joint projects shared by Venezuela and some member states.

Jose Chalhoub, a former security and risk analyst with PDVSA said PetroCaribe operations were under the control of a close relative of Hugo Chavez, Astrubal Chavez.

On its face, his appointment was clear nepotism. But what stands out is that all the people Astrubal Chavez dispatched to oversee the joint projects were also political appointees.

Chalhoub told CIJN there was no evidence any of them had experience in the oil industry. Between 2010 and 2012, Chalhoub and his team members traveled to Grenada, Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Vincent, Curacao, Bonaire and Domenica.

“Nepotism. I just saw corruption everywhere, mishandling of resources by a few, actually the Directors of PDVSA of these joint ventures in each of these islands,” Chalhoub said.

In El Salvador, he learned his security counterparts were headed up by a man who boasted he had been a leader within MARA, the gangs known today in the U.S. as MS-13. They appeared to be driving around in expensive cars and using Venezuelan money to host lavish dinners for members of the ruling leftist political party FMLN.

In Jamaica, his security counterparts warned fuel was being diverted from the PetroJam refinery for sale on the black market.

“We were also told (by members of the local team) that there were cases of oil spills, thefts and (unauthorized) pipelines connecting to the storage tanks in the Petrojam facility. They were denouncing that. They were reporting to us that those cases were current and something had to be done.”

As leader of international analyses, Chalhoub said when he and a team returned from these islands and filed their reports, complete with dire warnings of theft and corruption, they were simply shelved.

“It’s really sad and it’s really tragic but nothing substantial, nothing significant…any cure or any solution to these irregularities or issues” was enacted by PDVSA said Chalhoub. “Nothing was ever done.”

He said PDVSA never asked its security and risk control teams to make return trips to further investigate alleged corruption.

For more on PDVSA’s lack of oversight, see the complete interview with Jose Chalhoub.

The Case of Haiti

Two successive reports by Haiti’s Supreme Court have detailed corruption linked to public projects funded with US$ 1.7 Billion in PetroCaribe cash.

The latest came in May 2019. In it, the Supreme Court declared a lengthy list of crimes:

- Money laundering

- Illicit enrichment

- Illegal contract awards

- Overbilling

- Illegal commissions

- Bribes

- Influence peddling

- Nepotism

The court audited more than 419 projects. All were said to have several infractions.

In examining “FAES: Funds for Economic and Social Assistance,” the Court tried to reconcile its cost of US$78 million with what was delivered.

The Court’s finding was devastating. It concluded FAES was a “Total waste of money. 80,000 ghost beneficiaries. Exorbitant funds went to unrelated activities such as Carnaval festivities. Hundreds of thousands of beneficiaries did not receive payments.”

This single entry triggered a public outcry for the sheer number of impoverished Haitians who never saw a dime of the money meant for them.

As hospitals in Haiti have been forced to cut services, another audit struck a nerve. “Construction and Rehabilitation of Hospitals: Total Cost: US$ 78 million.” The Court’s finding included collusion, favoritism and breach of contracts.

The list goes on and on. More wasted money, embezzlement and deception.

Roadways never completed. Projects double billed. Funds diverted.

It was, indeed, an orgy of corruption.

It didn’t take long for Haiti’s 13 million people to find out. Riots broke out in the streets as Haitians demanded to know who stole their money.

Today Haiti is worse than broke. The country is US$ 2 Billion in debt, just where it was in 2008 when PetroCaribe’s first oil shipment arrived.

It can’t afford to buy fuel. As Haitians riot outside closed gas stations, fuel tankers wait in the harbor in full view of the population. When Haiti can’t pay, they sail away.

“Haiti has lost total credibility,” says Fritz Jean, the former Central Bank Governor, “it can no longer borrow.”

Former Prime Minister Evans Paul joined a chorus of critics who look back on eight years of mismanaged PetroCaribe funds:

“There was no vision. Plans changed from administration to administration. There were no specific trajectories or plans for development delineated, earmarked for funding. During 2010 there was the earthquake. Now we are ten years later and you can’t see any change. Just growing slums.”

And growing anger. Ordinary Haitians are clamoring for accountability. As Haiti descends into chaos, the protests grow louder and more threatening by the day.

(For more specifics on Haiti’s corruption crisis, see the Haiti Country Report.)

The Legacy of PetroCaribe

There is a strong consensus among analysts that during its lifespan, the PetroCaribe arrangement benefited member states US$ 28 Billion. For some, it not only shielded them from the shock of $100 a barrel oil prices but contributed to their economic health.

Dr. Anthony Gonzalez, former Director of the Institute of International Relations at the University of the West Indies in Trinidad, said some countries further benefited by paying off their debts with food, which they exchanged at inflated prices, “increasing their already healthy advantage in Petrocaribe deals.”

“Chavez wasn’t realistic,” offered Dr. Gonzalez, but “growth and GDP in Caribbean countries benefitted mightily from Venezuela’s largesse.”

There are success stories in how PetroCaribe funds helped furnish bottled gas to the poor and elderly on some islands. Other funds were invested in improving education, health and infrastructure. These benefits should not be ignored even as mismanagement and corruption command the headlines.

One of the concerns is PetroCaribe debt still outstanding. While countries like Jamaica jumped at the chance to use bonds to pay off what they owed Venezuela at a 50% discount, others have lingering balances.

Grenada noted in May 2019 that it still owed US$ 138 million or 11% of its GDP to PetroCaribe.

Some of the smallest island nations voiced concern they simply have no way to continue social programs that PetroCaribe helped fund in the past.

PetroCaribe created fiscal dependency far beyond just energy. Proceeds from the arrangement helped provide budget support, debt servicing and social development projects Caribbean residents embraced. Without PetroCaribe, countries may be forced to end those programs or borrow to fill the gap.

The Politics of PetroCaribe

The Caribbean islands that gave Venezuela their political support in votes at the Organization of American States now feel squeezed by U.S. sanctions and pressure. They can’t repay whatever they may still owe in U.S. dollars and some are putting those funds into escrow accounts.

When it comes to a vote, some abstain rather than having to choose a side and appear ungrateful to Caracas or risk angering Washington. They are uncomfortably sandwiched between two nations and know it.

Prime Minister Gaston Browne (Antigua & Barbuda) voices frustration over the sanctions. “These have prevented us from remitting monies to Venezuela, payments that we had for petrol that were coming to an end.”

Speaking of PetroCaribe, Prime Minister Brown says “it was a really great initiative. For us, it was like a godsend and now that it has come to an end, it has created some pressures on our economies.”

Nicolas Maduro’s strongest sympathizers are angry about the pain sanctions inflict on Venezuela.

“You don’t weaponize, even criminalize the system of trade…you don’t impose sanctions which would put a country under a medieval siege,” says Dr. Ralph Gonsalves, Prime Minister of St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

Dependency on Fossil Fuels

PetroCaribe’s member nations grew dependent on the hydrocarbon fuels it provided them. (The rest of the world, it should be noted, is also deeply dependent on hydocarbons.)

Some experts say another downside of PetroCaribe was that it set back the need to start looking for alternative energy sources in member states by years.

David Goldwyn, former U.S State Department Special Envoy for International Energy Affairs:

“The biggest legacy of Petrocaribe appears to be that it extended dependence on carbon fuels much longer then would have otherwise been the case…probably 8 to 10 years. Now they’re going through an energy transition to make themselves competitive but very late in the game.”

Goldwyn has called for the U.S. and others to provide the assistance necessary for Caribbean states to make that transition toward renewable energy.

PetroCaribe was conceived by Hugo Chavez at a time oil was enjoying the peaks of price success. He felt empowered.

“Chavez suffered from oil hubris. He overestimated the significance of oil and the geopolitical power it brought when oil was at $100,” said Dr. Anthony Gonzales.

Gonzales paused, adding “He was extraordinarily generous.”

If Caribbean nations are to draw any conclusions, they must take into account that volatile oil prices could soar again one day. They must be prepared.

El Presidente can no longer help them.

About Ingrid Arnesen

Ingrid Arnesen is an award-winning international journalist, television investigative producer and writer. Her work has spanned major international stories in Latin America, the Caribbean, the Middle East, Asia and Central Europe for CBS News, ABC News, CNN, and The Wall Street Journal. Ms. Arnesen is the recipient of the Peabody Award for her investigative work on terrorism, the Edward R. Murrow Award and Alfred I. Dupont Award for her coverage of Haiti. Ms. Arnesen is a contributor to the Daily Beast and independent documentary producer.

About Jim Clancy

Jim Clancy brings the experience of more than three decades covering the world to every project he engages. He didn’t just read about the collapse of Communism, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the siege of Beirut, the Rwanda Genocide, or all of the Iraq wars. He was there. His illustrious career includes award-winning reporting on the events that have shaped modern history. Now based in Atlanta and heading up his own Media Consulting business, Clancynet LLC, Jim is focused on documentary projects, photography and sharing his experiences with young journalists in the U.S. and around the world. In his 34 years with CNN, Clancy took viewers to places all over the world from Johannesburg to Shanghai and Beirut to Seoul. Today, he engages journalism students, moderates debates and speaks to the challenges facing today’s reporters. From 1982 to 1996, Clancy was a CNN international correspondent in the Beirut, Frankfurt, Rome and London bureaus. During this time, he won with the George Polk Award for his reporting on the genocide in Rwanda, the Alfred I. duPont Award for coverage of the war in Bosnia and an Emmy Award for reporting on the famine and international intervention in Somalia. In 2012, he won a national Emmy Award for his anchoring of the resignation of Pres. Hosni Mubarak of Egypt. Clancy has traveled extensively across Africa, meeting and interviewing Heads of State in Nigeria, South Africa, Sierra Leone, Algeria, Rwanda, Burundi, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Zimbabwe and more. For his work on Inside Africa, he received the A.H. Boerma Award 2000-01 from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization for increasing public awareness of global hunger. Clancy’s program ‘Inside Africa’ still appears on CNN and is the international network’s longest running feature. Jim Clancy joined CNN in 1981 as a national correspondent after an extensive, award-winning career in local radio and television in Denver and San Francisco. Follow Jim on Twitter: @ClancyReports

About Dale Elliott

Dale C. Elliott is a Saint Lucian Journalist and Communication Specialist. He is also the Founder and Managing Director of The Independent Film Company, Inc., which was incorporated under the Companies Act of Saint Lucia in 2011. The Company’s pièce de résistance is a social transformation and behavioural change documentary series entitled UNTOLD STORIES which is now into its 8th Season. There are currently approximately 130 documentaries covering an extensive range of topics that include, but are not limited to health, finance, crime, agriculture, environment, arts, and culture. Elliott has transformed the local media landscape through this series, by augmenting local programming content, and using the platform to educate and sensitize in a way that is palatable to varied audiences. Over the years he has received several awards for his work, the most notable of which are the coveted People’s Choice Award from the Saint Lucia Chamber of Commerce (2019), Most Outstanding Journalist from the Caribbean Congress of Community Practitioners in Barbados (2016 and 2015), and the Most Innovative Film Maker from the Piton Film Festival in Saint Lucia (2014).

About Kimone Francis

Kimone Francis is a senior reporter at the Jamaica Observer who covers politics, offering in-depth reporting and analysis on national and international issues.

SOURCE: https://www.cijn.org/venezuela-petrocaribe-and-the-orgy-of-corruption/